The ocean sunfish (Mola mola), also known as the common mola, is one of the largest bony fish in the world.,known for its distinctive appearance and unique behavior, has captivated marine biologists and ocean enthusiasts alike. This large, peculiar fish is a member of the family Molidae and is recognized as one of the heaviest bony fish in the world. In this article, we’ll explore the biology, ecology, and conservation of the ocean sunfish, providing a comprehensive look at this extraordinary creature.

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes)

Order: Tetraodontiformes

Family: Molidae

Genus: Mola

Species: Mola mola

The Ocean Sunfish (Mola mola) belongs to the family Molidae, which includes other large sunfish species. It's classified within the Tetraodontiformes order, which also contains pufferfish and triggerfish. The genus Mola comprises a few closely related sunfish species, with Mola mola being the most well-known due to its size and distinct body shape.

The study of ocean sunfish dates back to the early 18th century when it was first described by naturalists. The ocean sunfish was long considered a strange anomaly in marine biology due to its size and unique body shape. Over the years, researchers have discovered fascinating aspects of its behavior, diet, and ecology, contributing significantly to marine zoology.

The Ocean Sunfish (Mola mola) is one of the most distinctive and unique marine species, with a remarkable set of physical characteristics that set it apart from other fish species. Below are the key morphological and physical traits of this extraordinary fish:

The most striking feature of the ocean sunfish is its flattened, oval-like body. The body is so wide and short that it often looks like a floating head with a small tail, which is a primary reason for its name "sunfish."

The body structure is asymmetrical in appearance, and it lacks the typical streamlined shape of most fish. Instead, it has a tall, broad form that allows it to rise vertically to the ocean's surface and bask in the sun.

Unlike most fish, the ocean sunfish does not have a true caudal fin (tail fin). Instead, it has a unique structure known as a clavus, a fused, rudder-like structure made up of the dorsal and anal fins.

The clavus is short and triangular, functioning somewhat like a tail, helping the sunfish to stabilize and maneuver, although it doesn't enable fast swimming. This modification is a key distinguishing feature of the species.

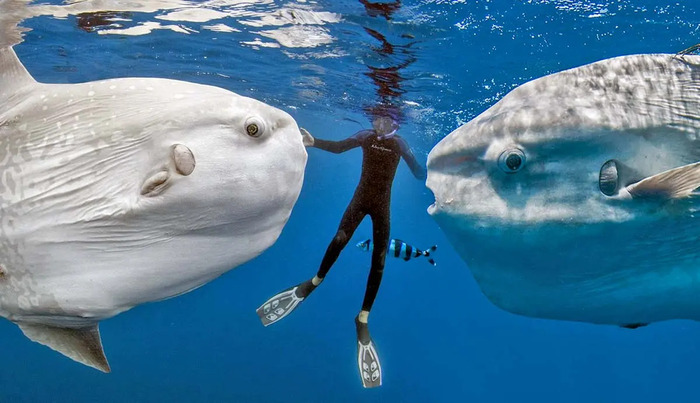

Length: Adult ocean sunfish can grow to impressive sizes, typically ranging from 1.8 meters (6 feet) to 3 meters (10 feet) in length. The largest recorded specimens have reached lengths exceeding 4 meters.

Weight: These giant fish are the heaviest bony fish in the world, with average weights between 1,000 kg to 2,200 kg (2,200 lbs to 5,000 lbs). Despite their large size, they have relatively low body density due to their soft, gelatinous bodies.

Massive Size: Some of the largest sunfish can weigh up to 5,000 pounds, making them one of the heaviest fish species.

The skin of the ocean sunfish is one of its most distinctive and fascinating features. It serves both a functional and protective role, adapting to the fish's unique lifestyle and environment.

Adult ocean sunfish display a range of colors from brown to silvery-grey or white, often with mottled patterns that vary by region. This coloration helps the fish blend into its environment, offering some degree of camouflage in the ocean. The skin is typically darker on the dorsal (top) surface and lighter on the ventral (bottom) surface, a pattern known as countershading. This coloration helps to disguise the sunfish’s body, particularly when viewed from above or below, making it harder for predators to spot.

Interestingly, Mola mola also has the ability to change its skin color, darkening or lightening depending on environmental conditions, particularly when the fish is under threat or stressed. This color-shifting behavior may serve as a defensive mechanism.

The skin of the ocean sunfish is thick and tough, with large amounts of reticulated collagen, which gives it a unique texture and strength. On the ventral surface, the skin can be as thick as 7.3 cm (2.75 inches), providing a protective barrier against environmental stressors and physical damage.

The skin itself is covered by denticles, small tooth-like structures that give it a rough texture. This texture can be compared to sandpaper, especially on the body. The clavus (pseudo-tail) is smoother in comparison, contributing to its different texture and appearance.

The ocean sunfish's skin is a popular host for numerous parasites, including more than 40 different species that live both externally and internally. One of the most common parasites is the flatworm Accacoelium contortum, which can be found attached to the fish's skin or within its body. These parasites often irritate the fish and can reduce its health, which is why ocean sunfish engage in various cleaning behaviors.

To rid itself of parasites, the sunfish utilizes several strategies:

Basking at the surface: By basking on its side, especially in temperate and tropical waters, the ocean sunfish provides an opportunity for cleaner fish like cleaner wrasses and other species to remove parasites from its skin. These cleaner fish feed on the parasites, helping to maintain the sunfish’s health.

Seabird interactions: In addition to fish, seabirds are known to help clean the sunfish by feeding on parasites that cling to its skin. This mutualistic behavior benefits both the birds and the sunfish.

Kelp fields: In some regions, sunfish are frequently found in drifting kelp fields, where they seek the help of cleaner wrasses and other fish species to rid themselves of parasites.

Breaching: Occasionally, sunfish are reported to breach the water's surface, jumping clear of the water by up to 3 meters (10 feet). This behavior is believed to help the fish dislodge embedded parasites or simply shake off the irritants, contributing to their overall health.

The ocean sunfish’s skin is not only a protective barrier but also an essential component of its ecological interactions. Its unique thick, collagen-rich skin, denticle-covered texture, and countershading coloration provide it with defense mechanisms against predators and environmental challenges. Additionally, the sunfish's parasite-removal behaviors, including interactions with cleaner fish and seabirds, are critical to maintaining its health and comfort in the vast ocean. These fascinating skin characteristics are a testament to the sunfish's adaptation to life in the open sea.

Ocean sunfish have large dorsal and anal fins that are positioned very far back on their bodies. These fins are used for propulsion and maneuvering, but they are not very efficient at fast swimming.

The pectoral fins are broad and help stabilize the fish when it moves, although it typically swims at a slow pace.

In the course of its evolution, the caudal fin (tail) of the sunfish disappeared, to be replaced by a lumpy pseudotail, the clavus. This structure is formed by the convergence of the dorsal and anal fins, and is used by the fish as a rudder.The smooth-denticled clavus retains 11–14 fin rays and terminates in a number of rounded ossicles.

The eyes of the ocean sunfish are relatively small compared to the size of their body, but they have excellent vision that aids them in detecting movement and light changes around them. Their eyes are positioned toward the front of their head, making them capable of seeing above and below them when basking at the surface.

The ocean sunfish has a small mouth compared to its overall size, with no teeth or jaws. Instead, it has a unique, beak-like structure made of tough, sharp-edged plates, which helps it feed on soft-bodied prey like jellyfish.

Ocean sunfish lack a swim bladder, a common feature in most fish species, which helps regulate buoyancy. Instead, they maintain their buoyancy through a combination of their large, soft body and the gas-filled cavities in their internal organs.

Heart and Circulatory System: Like many large fish, ocean sunfish have a large, powerful heart capable of pumping blood efficiently through their massive bodies, supporting their slow but steady movements through the ocean.

Due to their unique shape, ocean sunfish are not particularly fast swimmers. Their movement is more of a slow, deliberate drifting, often aided by ocean currents. They can dive to great depths, often to colder waters, where they feed on jellyfish and other invertebrates.

Their sunbasking behavior is thought to be an adaptation to regulate their body temperature, as they are ectothermic (cold-blooded) and lack the ability to generate heat internally. By spending time near the ocean's surface, they can absorb sunlight, which helps them warm up after deep dives into colder waters.

The typical lifespan of an ocean sunfish is around 10 years, although some individuals can live longer. They grow at a rapid rate during their early years, reaching maturity at about 4 years old.

Ocean sunfish are found in both temperate and tropical oceans across the globe. They tend to inhabit deeper waters but are often seen near the surface, where they bask in the sun or interact with cleaner fish. These sunfish are known to be widely distributed from the coasts of California to the waters off Japan, New Zealand, and the Mediterranean Sea.

The ocean sunfish primarily inhabits deep, offshore waters, although they can sometimes be found close to the coast. They are often seen in areas with strong ocean currents and water temperatures ranging from 10°C to 20°C (50°F to 68°F). The fish’s behavior of basking at the surface is believed to help regulate its body temperature, as they lack the ability to generate significant heat on their own.

Despite their massive size, ocean sunfish are solitary creatures. They are often seen near the surface, basking in the sun, and may swim in circles. This behavior is thought to be linked to their need for warmth, as they have a relatively low metabolic rate.

While ocean sunfish do not typically form large groups, they may occasionally be observed interacting with other species, including smaller fish that help clean their bodies of parasites. These interactions are symbiotic, benefiting both the ocean sunfish and the cleaner fish.

Ocean sunfish are opportunistic feeders and primarily consume jellyfish, but their diet can also include small fish, squid, and plankton. Their feeding strategy revolves around the consumption of large quantities of jellyfish, which are abundant in the open ocean. Due to the lack of significant nutritional value in jellyfish, ocean sunfish need to consume large volumes to sustain themselves.

The sunfish lacks a swim bladder. Some sources indicate the internal organs contain a concentrated neurotoxin, tetrodotoxin, like the organs of other poisonous tetraodontiformes,while others dispute this claim.

The ocean sunfish (Mola mola) exhibits fascinating reproductive strategies that help ensure the survival of this extraordinary species, despite the challenges posed by its massive size and the open-ocean environment it inhabits.

Ocean sunfish reach sexual maturity relatively early compared to their long lifespan. Typically, sunfish become reproductively active around 4 years of age, although they can continue to grow for several more years. The timing of reproduction varies with location, but sunfish generally spawn in warmer waters during the late spring to early summer months, aligning with optimal environmental conditions for the survival of their offspring.

One of the most remarkable aspects of the ocean sunfish’s reproduction is the sheer quantity of eggs a female can produce. A single female can lay an astonishing number of eggs—up to 300 million eggs in one spawning event. This enormous egg production is a strategy to increase the chances of offspring survival, given that only a tiny fraction of these eggs will survive to adulthood.

The process of fertilization in ocean sunfish is external, a common trait among many marine species. During the spawning season, females release their eggs into the open water, where they float near the ocean's surface. The male sunfish then releases sperm to fertilize the eggs externally. This method of fertilization is known as broadcast spawning, where both eggs and sperm are released into the water column to mix and fertilize the eggs.

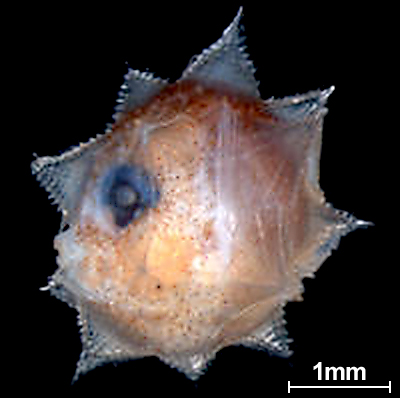

Once fertilized, the eggs hatch into tiny larvae, measuring only about 2–3 mm in length at birth. Despite their small size, these larvae grow rapidly, undergoing a series of transformations before becoming juvenile sunfish. The larvae have a planktonic stage, where they drift with ocean currents before eventually sinking to the ocean floor and beginning their development into more recognizable forms of the adult fish.

As the larvae grow, they undergo significant morphological changes, including the development of the characteristic large body and the loss of the initial juvenile fin structure, which will later become their unique, disk-like body with the clavus.

Ocean sunfish do not provide any parental care to their offspring. Once the eggs are fertilized and the larvae hatch, the young are left to fend for themselves in the vast ocean. The high number of eggs is a compensatory measure for the lack of parental care, as the survival rate of individual sunfish larvae is very low due to predation and other environmental challenges.

Despite these odds, ocean sunfish larvae that survive the early stages of their life cycle grow quickly. The fish undergo rapid juvenile growth, achieving significant size within a few years, though they will continue to grow throughout their life, potentially reaching several tons in weight by adulthood.

The reproductive strategy of the ocean sunfish is centered around massive egg production and external fertilization, ensuring that even with the challenges of ocean life, the species continues to thrive. While the survival rate of individual offspring is low, the sheer number of eggs and the ability to grow rapidly after hatching increases the likelihood that some sunfish will survive to maturity. This strategy of quantity over quality in reproduction is key to their ongoing existence in the world's oceans.

The ocean sunfish is not currently listed as endangered, but its populations face numerous threats. Conservation efforts focus on reducing bycatch in commercial fishing operations, which can accidentally capture these large fish. Organizations are also working to monitor and protect the sunfish's habitats, especially in areas where they are at risk of entanglement in fishing gear.

Ocean sunfish face several natural predators, including large sharks and orcas. However, humans present the most significant threat to their populations, particularly through fishing practices. Additionally, ocean sunfish are vulnerable to marine pollution, including plastic debris and entanglement in nets, which can lead to injury or death.

Ocean sunfish play a crucial role in marine ecosystems, particularly in regulating jellyfish populations. By consuming large amounts of jellyfish, sunfish help maintain a balance in the marine food web. Their large size and feeding behavior also support other species, such as cleaner fish, that depend on them for food and shelter.

While ocean sunfish are not typically targeted for commercial fishing, they contribute to local economies through eco-tourism. Whale watching and sunfish spotting tours are popular in certain coastal areas, providing significant revenue for local communities. Additionally, their role in controlling jellyfish populations is beneficial for maintaining the health of commercial fisheries.

Ocean sunfish belong to the family Molidae, which includes several closely related species. Here’s a quick look at some of them:

| Species Name | Common Name | Distribution Area | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mola ramsayi | Southern Ocean Sunfish | Southern Hemisphere | Smaller, but similar body shape to Mola mola |

| Mola tecta | Hoodwinker Sunfish | New Zealand, Australia | Smaller, more recent discovery, unique tail features |

| Ranzania laevis | Smooth Sunfish | Temperate waters globally | Smooth, elongated body, less circular than Mola mola |

Ocean sunfish (Mola mola) is not commonly eaten due to its tough, gelatinous texture and lack of muscle mass, making it unappealing for most culinary purposes. Its flesh is not considered flavorful or desirable by many cultures, and it is often described as bony and fatty. In some regions, however, sunfish is used in traditional dishes or occasionally consumed as sushi. Despite this, it is not a popular choice in most cuisines. Additionally, ocean sunfish are often protected by conservation laws, limiting their availability for consumption.

The exact number of ocean sunfish (Mola mola) in the world is not well-documented, as these creatures are difficult to track due to their vast, open-ocean habitats. However, they are generally considered not endangered, with a stable population globally. Despite this, the species faces threats from bycatch, pollution, and habitat degradation, which could affect their numbers over time.

While no precise count is available, conservation efforts and the species' prolific reproductive strategy—producing up to 300 million eggs—help maintain their population in the wild. However, localized declines may occur, particularly in regions where human activity is most concentrated.

The ocean sunfish is an extraordinary marine species with unique characteristics and behavior. While it isn’t currently endangered, it faces several threats from human activities and natural predators. By continuing to study and protect this fascinating creature, we can ensure that the ocean sunfish continues to thrive in the world’s oceans for generations to come.

If you're looking for an exciting marine animal to learn about or see in the wild, the ocean sunfish offers a remarkable and educational experience. Its sheer size, strange appearance, and interesting ecological role make it a standout among the diverse inhabitants of our oceans.

animal tags: Molidae

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.