Some complex behaviors in biological evolution are difficult to observe in fossil evidence. Parental care (referring to the protection and feeding of offspring by parents) is an important adaptive behavior in the evolution of higher life, and it is also the key to the social nature of arthropods. Parental care behavior has evolved independently many times in the evolutionary history of life, and is widely found in insects and other arthropods, as well as vertebrates, such as mammals, birds, dinosaurs and other animal groups.

The scientific research team of researcher Huang Diying from the Nanjing Institute of Paleontology studied my country's Middle Jurassic Daohugou Biota (about 165 million years ago), the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota (about 125 million years ago), and the early Late Cretaceous Burmese amber (about 165 million years ago). 99 million years old), the phylogenetic evolution and ultrastructural functional morphology of the Mesozoic beetle fossils were analyzed, deciphering the parental care behavior of Mesozoic beetle insects, and revealing the secrets of the evolution of some complex behavioral characteristics in these small beetles.

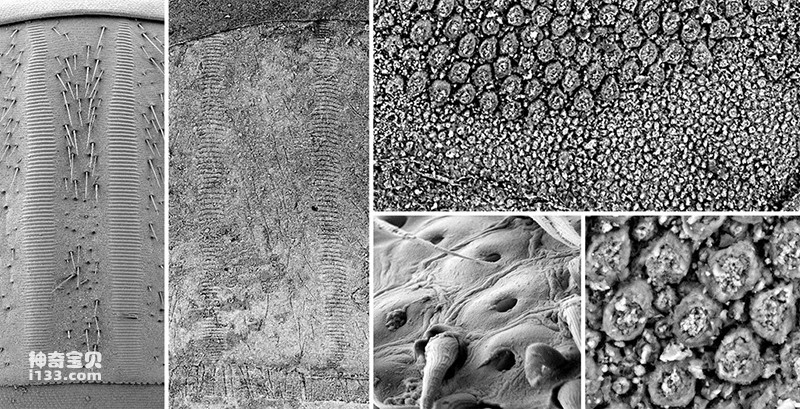

Left: Buried beetles from the Middle Jurassic Daohugou Biota (165 million years ago); Middle: Buried beetles from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Insect Group (125 million years old); Right: Early Late Cretaceous Burmese amber Burial Armor (99 million years)

Silphidae is a small family in the order Coleoptera of insects, with less than 200 extant species. Scientists usually focus on burial beetles not on taxonomy but on their complex behaviors, such as their subsocial lifestyle, parental care behavior, scavenging habits, and characteristics of their buried food. Because burial beetle fossils are very rare, the origin, background mechanism, and evolutionary development of these complex behaviors are unknown. The only burial beetle fossils come from the late Eocene Florissant Biota in Colorado, USA (approximately 35 million years old). In recent years, Huang Diying and his doctoral student Cai Chenyang have discovered a large number of Mesozoic burial beetle fossils, including 37 from the Middle Jurassic Daohugou Biota, 5 from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota, and 6 individuals from the Late Cretaceous Myanmar. Amber, under the scanning electron microscope, the vocal files on the abdomen of the fossil beetle, the chemical receptors on the antennae, etc. were discovered, which provided new insights into the complex behavioral mechanism of the beetle insect.

Scanning electron micrographs of modern and fossil fungus rasps and antennal chemoreceptors

The discovery of the fossil beetles of the Daohugou biomass has advanced the fossil record of the family Beetidae by 130 million years. However, there does not seem to be much difference in morphology between these ancient beetles and modern species, such as: rod-shaped antennae, The huge midthorax scutes and transverse elytra show the morphological stability of the burial armor over 165 million years. Observation of the ultramicrostructure through scanning electron microscopy revealed that the ends of the tentacles of these fossil beetles were densely covered with tiny chemical receptors, and like modern species, they had two types of receptors: spherical and conical. Modern beetles rely on these chemoreceptors to detect the stench of carrion, and they are scavengers—feeding on decaying mammal and bird carcasses. In the Middle Jurassic before the appearance of blowflies (common species such as red-headed flies, whose larvae are maggots), burial beetles had already appeared in large numbers in the ecosystem, playing an important role as scavengers.

The burial armor fossils in the Jehol Biota of the Early Cretaceous do not look significantly different from those of the Middle Jurassic, but they have two rows of file-like structures composed of tiny transverse ridges on their third visible ventral plate, and The friction between the inner edges of the elytra produces a chirping sound. Modern burial beetles will create holes in carrion to lay eggs and raise a clutch of larvae in them. The "parents" will take care of the offspring. This is a typical parental care behavior and constitutes a simple social division of labor, but it has not yet formed a strict division of labor. Hierarchy, so beetles are called subsocial insects. In the process of raising offspring in the burial armor, this small sound file plays a vital role. One of the important natural enemies of modern burrowing beetles is some types of cryptid subfamily, which are ferocious predators with huge upper jaws. In his doctoral thesis research, Cai Chenyang discovered the Mesozoic fossil records of most subfamilies of Cryptozoa, and these ferocious predators of the Cryptozoa subfamily also appear in the Jehol Biota, and even come from the same fossil origin as the Burial Beetle. Therefore, there is reason to believe that these large predatory cryptids may have been the natural enemies of the Burial Beetle at that time. When the beetle is attacked by natural enemies, it can use its elytra to make a sharp chirping sound to scare off the predators. Perhaps it was the emergence of deadly natural enemies that led to the creation of the Cretaceous burial beetle's rasp, reflecting an ingenious survival strategy. In addition, the chirping of the burial beetle is also an important means of communication with the larvae. Due to the emergence of sound files, the burial beetles in the Jehol Biota have already possessed rudimentary parental care habits, such as protecting larvae.

Ecological restoration map of Early Cretaceous burial armor

The age of the Jehol biomass beetle fossils is earlier than the earliest geological records of other social insects. For example, the earliest ants were found in French amber in the mid-Cretaceous (about 100 million years old), and the earliest bees may have existed in Burmese amber (about 0.99 years old). billions of years), and the earliest termites discovered so far are slightly later than the Jehol Biota. Therefore, the discovery of subsocial beetles in the Jehol Biota is also the earliest fossil record of (sub)social insects.

Although the burial beetle fossils of the Daohugou and Jehol biota show a high degree of stagnant evolution, their antennal characteristics are still different from modern species, and they belong to the extinct type. The 8-10 tentacles of the fossil beetle first discovered in Burmese amber about 100 million years ago are specialized and flaky, with no significant morphological difference from modern types, and can be classified into the living genus Nicrophorus. The most peculiar habit of the genus Burybug is to bury the corpses of small mammals and birds (generally less than 200 grams) under soft soil to form corpse masses, and lay eggs on them as long-term food resources for the larvae. Fossil evidence from the Jehol Biota shows that birds and mammals had significantly differentiated and miniaturized at that time. Therefore, some burial beetles in the mid-Cretaceous may have had complex parental care behaviors of burying small mammal or bird carcasses, storing food for their larvae, and feeding their offspring.

The morphological stability of the Mesozoic beetles reveals that the origin of the beetles may be traced back to the late Triassic. With the emergence of mammals, the ancestors of the beetles developed unique scavenging habits and corresponding morphological structures. The ancestors of Pteridae broke away to form an independent group. The stability of living habits and food sources during the long geological history has determined that the morphological structure of the burial armor has been extremely small.

animal tags:

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.