Sabre-toothed cats were widely distributed in the Neogene and Quaternary periods of the New and Old Worlds. They are a long-lasting group of carnivores. They first appeared in the middle Miocene and coexisted with humans until the early Holocene. Extinction. There is evidence that the demise of the ferocious saber-toothed tigers may be attributed to humans' growing ability to eventually overcome them and even regard them as prey. Similar to living big cats, large saber-toothed tigers have hunting advantages. Some saber-toothed tigers are close to the size of lions or tigers. For example, the adult Smilodon populator can weigh more than 400 kilograms. On the other hand, most of the saber-toothed tiger fossil materials obtained early were too fragmented, so there are still many unsolved mysteries about their body size differences and evolutionary processes. Only in recent years have several complete saber-toothed tiger skulls been discovered in Europe and China. Among them, Machairodus horribilis is the largest known saber-toothed cat. There are also significant morphological differences between the skulls of saber-toothed cats, with some types being highly specialized, such as Smilodon and Homotherium, while others are more closely related to modern big cats, members of the subfamily Leopardinae. The discovered saber-toothed cat fossil material depicts the mosaic evolution of this group and characterizes their morphological and ecological diversity during the process of adaptive radiation.

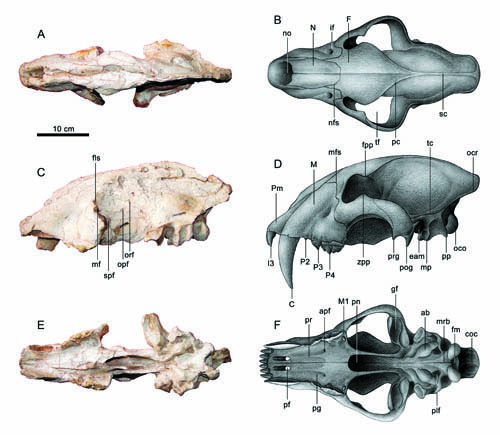

Deng Tao and others reported in the latest issue of "Vertebrata PalAsiatica" (Vertebrata PalAsiatica) that a large-scale three-toed horse red soil was collected from the late Miocene in Wudu, Gansu Province (7.25 to 5.3 million years ago). The Smilodon skull, representing a male individual. The top line of this skull is 415 millimeters long, longer than any previously known saber-tooth cat skull, and its weight was calculated to be 405 kilograms. Their anatomical features provide new evidence for differential hunting patterns even among the largest saber-toothed carnivores and reveal another mechanism that led to the evolution of a mosaic of functional and morphological diversity in saber-toothed cats.

Combined with the previously discovered skull fossil of a slightly smaller and possibly female Smilodon cat from the same era in Baode, Shanxi, the fossils from Wudu indicate that this Smilodon species relied on its unspecialized species in the woodlands or grasslands of northern China during the late Miocene. The throat stabbing method subdues the prey. Its huge size would have allowed it to hunt common large ungulates, but the insufficient distance between its upper and lower canine teeth limited the types of prey it could prey on.

Large body size affects many aspects of animal structure and function. Among extant carnivores, almost all species weighing more than 21 kilograms hunt prey that is equal to or larger than their body weight, which is consistent with an energy-saving strategy. Because saber-toothed cats were generally strong animals, they are thought to have been specialized to hunt larger prey than modern big cats. Differences in carnivorous hunting and feeding behavior are often reflected in the morphology of their skulls and teeth, with convergent evolution occurring in mammals and Lesbosaurus dinosaurs that also had sword-shaped teeth. Bigger prey corresponds to bigger prey, so does the huge size of Diresabertooth indicate that it must hunt very large prey? Or does it have a unique hunting mechanism?

Indeed, several features indicate that Smilodon used its canines to penetrate the throat and cause massive blood loss to kill prey, much like behavior inferred from more advanced saber-toothed cats. These features include: high-crowned, flat and serrated upper canine teeth, which are ideal for piercing the flesh of prey but less suitable for crushing the back of the neck or suffocating the throat; enlarged mastoid ridges, anteroposterior orientation The slightly raised mastoid process on the upper part of the head and the middle ridge at the base of the head indicate the location of muscle attachment, which is consistent with adaptation to canine stabbing behavior; the elongated and tilted occipital region can better enable the anterior teeth to move through the movement of the temporalis muscle when the upper and lower jaws are closed. (incisors and canines) produce greater force than cleft teeth.

On the other hand, there are also significant differences among saber-toothed carnivorous mammals, indicating their behavioral and ecological diversity. If throat stabbing is the main hunting technique of saber-toothed cats, then hunting large prey requires a greater degree of mouth opening. For example, the large mouth of saber-toothed tigers can reach 120°. However, Smilodon had well-developed anterior and posterior articular processes, which made the glenoid fossa connecting the skull and mandible very deep, similar to modern leopards, such as lions and leopards, so its mouth opening was limited to only Medium level around 70°. Furthermore, the sloping occipital part of D. diretodon indicates that the fibers of the temporalis muscle were strongly slanted like in primitive cats, whereas in progressive S. sabretooth the orientation of these muscle fibers became more vertical. The sloping temporalis muscle of D. sabertooth restricted its extension on the dorsal side of the head, correspondingly reducing the head movement required for canine stabbing movements. Although the unusually developed mastoid ridges of Diretodon provided a larger area for atlas-mastoid muscle attachment and indicate that these muscles were more powerful than in the subfamily Leopardinae, they were less effective than in the more advanced Smilodon. Therefore, functional morphology shows that the hunting mechanism of Diresabertooth is different from that of more specialized saber-toothed cats, but is similar in some aspects to living lions and leopards and primitive early cats, allowing it to hunt only relatively small animals. prey.

The highly mosaic evolution of saber-toothed tigers is shown in the perfection of the canine stabbing behavior, which is intended to kill their prey more effectively in order to reduce fighting time and avoid saber tooth breakage and prey escape. The canines of Machairodus giganteus and M. aphanistus were flat and therefore brittle and breakable. In order to make up for this defect, Diresabertooth had thick incisors like a hyena, especially the third incisor, and the incisors were arranged in a gentle arc. Its function was to assist the canine teeth in controlling the struggle of the prey during hunting.

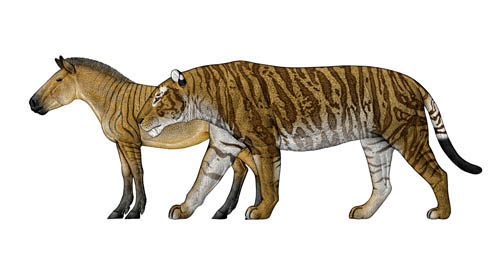

The hunting behavior of the saber-toothed cat was different from that of modern big cats, as well as from more advanced saber-toothed cats such as sawtooth tigers and saber-toothed tigers. Among the late Miocene mammals in Wudu, there are forest animals such as ancient apes and clawed beasts, as well as typical open area animals. Among them, the flat-toothed three-toed horse (Hipparion platyodus) with short limbs and slow running may be the saber-tooth cat of Dire. main prey. As prey, Eostyloceros and Cervavitus were too small and too fast for the saber-tooth cat, while the giraffe-like Samotherium and Honanotherium were too large and other The hooves can easily injure predators.

A key advantage of the initial development of sword-shaped teeth was the effectiveness of the stabbing action, which would cause massive blood loss rather than suffocation of the prey, and the size of the prey was not the purpose. Since then, more advanced saber-toothed cats with larger mouth openings and more specialized musculoskeletal combinations have evolved the ability to hunt larger prey. Although it has the largest skull of all saber-toothed cats, it has a mixture of primitive and advanced morphological characteristics and does not exhibit the hunting techniques of advanced types such as saber-toothed cats and serrated cats, so it can only hunt relatively small prey. Hunting behavior apparently evolved independently multiple times throughout the saber-toothed cat's history as the environment and prey evolved.

Figure 1 Dreaded saber-toothed tiger hunting scene (painted by Chen Yu)

Figure 2 Fossil skull of Sabretooth Cat and its correction and restoration (drawn by Chen Yu)

Figure 3 Comparison of the body shape of the saber-toothed tiger and its main prey, the flat-toothed three-toed horse (drawn by Chen Yu)

Figure 4 Comparison of the opening degree of the mouths of Smilodon and Smilodon (illustrated by Michael Long) (Photo provided by Deng Tao)

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.