Macaca munzala

IUCN

LCBasic Information

Scientific classification

- name:Macaca munzala

- Scientific Name:Macaca munzala

- Outline:Primates

- Family:M.family M.sapiens

Vital signs

- length:About 56 cm

- Weight:About 15kg

- lifetime:20-40years

Feature

It was only confirmed as a new species in 2004.

Distribution and Habitat

Distributed in high altitude areas of southern Tibet, China. The type locality is 27°42'N, 91°43'E, at an altitude of 2180 meters. It is mostly distributed in the western part of Xikamen County, Tawang, southern Tibet, and is most common in the Tawang area of the region, although it has also been found in Xikamen and may also occur in other areas outside southern Tibet, as well as in adjacent areas of Bhutan and Tibet (China). Based on available field data, the range of possible data for the occurrence of this species is 3700 square kilometers, and the area occupied is about 2700 square kilometers. It is also distributed in Mouling National Park, adjacent to southern Tibet.

The distribution of the southern Tibetan macaque is believed to be restricted in the east by the Brahmaputra River. This isolates it from a closely related species, the eastern bear monkey.

The species is only found in high mountain areas at an altitude of 2000-3500 meters. Lives in degraded broad-

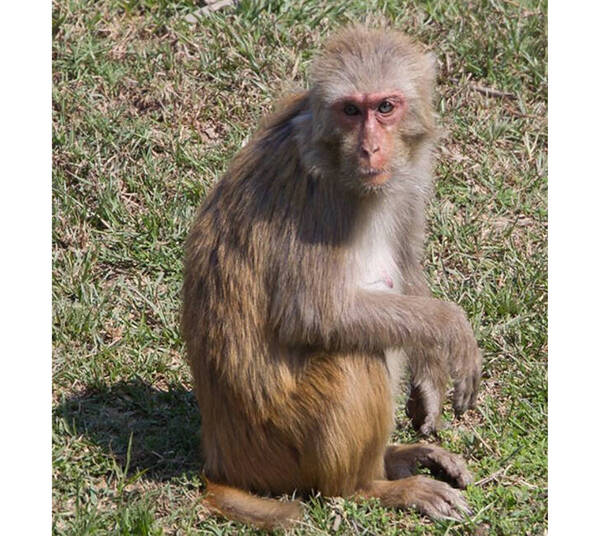

Appearance

The Tibetan macaque weighs 15 kg, has a total length of 824 mm, a head and body length of 560 mm, and a tail length of 264 mm. It is a relatively large brown macaque with dark cheeks and a small tuft of distinctive yellow hair on the forehead, including a black central whorl. The most distinctive features are the light-colored fur on the neck, dark spots on the forehead and face, and a dark stripe above the eyes. The hair around the neck is light in color. It has a relatively short tail compared to other monkeys of the same genus.

It is large and stocky, with dark brown or black-brown fur on the upper body, which becomes shiny on the forelimbs. The hair is long and dense, especially on the upper body. The tail is short, 39%-45% of the body length. This distinguishes them from closely related species. The ears are dark, the nose is flared, and the skin around the eyes is lighter.

Like many macaques, the Tibetan macaque is sexually dimorphic. Males are larger than females, with lon

Details

The Southern Tibetan Macaque (scientific name: Macaca munzala) is a typical macaque animal with no subspecies.

The Southern Tibetan Macaque is native to the southern Tibet region of China (now occupied by India). Its species name "munzala" comes from the Zhairang Monpa tribe, pronounced "diep-bosaap" and means "deep forest monkey". Named by the famous Indian primatologist Anwaruddin Choudhury in 1997, the southern Tibetan macaque was once considered a subspecies of the bear macaque, but was only identified as a new species in 2004. The first species of this macaque was discovered in 1903 on Pagai Island, Indonesia. In 2011, some researchers suggested that it might be better regarded as a new species based on the morphological variation of the bear macaque. The southern Tibetan macaque has independent morphological characteristics, and like the bear macaque and the Tibetan macaque, the southern Tibetan macaque seems to belong to the Chinese population of the genus. However, the species is unique in relative tail length, which is between the Tibetan macaque and the bear macaque, while the bear macaque living in the same area is a subspecies of the bear macaque.

The home range of the Tibetan macaque varies greatly, depending on the size of the group, and is fairly loosely defined. Smaller groups may have a small range of 7 hectares; larger groups may have a range of no more than 55 hectares. The range use of a particular group varies by season. In the spring and summer, Tibetan macaques vary more in their itineraries to access food resources. In the winter, they are more inclined to stay in one place, relying on whatever resources they can find locally.

Tibetan macaques are social animals. They live in groups of 5-60 individuals, with an average of 21.6 individuals per group. These groups include males, females, juveniles, and infants, all of which usually coexist in a peaceful and cooperative manner. Groups forage together during the day and often engage in mutual social grooming and petting. Mutual grooming is most common among adult males of the same sex, while young monkeys are groomed by adult females. Antagonistic behavior is rare and is usually limited to threats. These threats are more common in winter, when food supplies are scarce and competition is intensified. Macaques in general are highly social species with complex dominance and hierarchy systems. The group structure of the southern Tibetan macaque, although not specifically described, is no exception. The southern Tibetan macaque has a matriarchal structure, and the ranking of an individual macaque mother likely helps determine her future status.

The southern Tibetan macaque is diurnal and primarily terrestrial. They are capable of climbing and spending the night in trees. During the day, they remain on the ground and forage for food. They spend a large amount of time eating or searching for food. In the summer, eating accounts for 29%-51% of their daily activities, while in the winter this number can increase to 41%-66%. The southern Tibetan macaque group has well-defined family territories, which may overlap. Macaques interact peacefully at the boundaries of these home ranges, which they rarely leave except to obtain food. Within these ranges, macaques can travel long distances to forage for food. Foraging may account for up to 50% of the summer activity budget. In winter, Tibetan macaques are reluctant to travel because they need to conserve energy. During this season, they move very little, stay in one place, and survive on large quantities of low-quality food. Another energy-saving measure adopted by Tibetan macaques is resting. They spend more time resting than individuals of related species, most likely due to the cooler temperatures and higher altitudes of their habitat. During the day, they often bask in the sun, spending most of their time there. A variety of other behaviors have been observed in Tibetan macaques, but have not been reviewed in detail. These include male-group differentiation turbulence (which may serve as a dominance display), sexual inspection of females by males, and fixed positioning of males against males.

Most macaques communicate vocally and visually. Vocal communication, while not yet documented in Tibetan macaques, almost certainly exists, and a variety of visual displays are known. These displays may include facial expressions, body postures, and other behaviors, such as shaking a branch. They often use these to communicate, intimidate aggressors, or dominate relationships. Tactile communication has also been observed in southern Tibetan macaques. Mutual grooming is a common social activity in many primates that promotes bonding between individuals.

The southern Tibetan macaque is almost entirely herbivorous, feeding on about 29 different plant species. Sometimes they will eat small invertebrates or dirt, but the vast majority of their diet is leaves and twigs. Other parts of plants, such as fruits, flowers, stems, and bark, are sometimes eaten. The vast majority of their diet consists of only a few plant species. In the spring, seven foods make up 75% of their diet, while in the winter, seven foods make up 75%, a diet that is much less diverse and nutritious.

In the winter, the macaques travel shorter distances to find food, and they survive on whatever low-quality ingredients they can find locally. They also switch from eating leaves and fruits to less nutritious bark and pith. The most important part of the macaques' diet is a single plant, Erythrina, which monopolizes more than 72% of feeding time in the winter and about 19% in the spring. This plant is very common in the areas where the macaques live and dominates the areas where they spend the winter.

The macaques are only found in the southern Tibet region of China, which is home to medium to large predators. This is where jackals, Asiatic black bears, and snow leopards live. These beasts are known to sometimes hunt monkeys, while the other two can take prey of similar size. However, none of them are known predators of the southern Tibetan macaque. The southern Tibetan macaque is occasionally killed by humans, usually in retaliation for crop destruction. They are not usually eaten by humans in most of their range, but may be hunted for use in traditional medicine. This makes humans the only confirmed predator of the southern Tibetan macaque.

The reproductive system of the southern Tibetan macaque is not well known. Several sexual behaviors have been observed in this species, including mounting and genital inspection. However, mating behavior has never been specifically described. Closely related macaques are polygynous or multiparous, and the southern Tibetan macaque may reproduce in the same manner. Their multi-male, multi-female group structure suggests this may be the case.

The mating system is monogamous. The average number of offspring, breeding season, birth weight, weaning age, age of independence, and age of sexual maturity of the southern Tibetan macaque are unknown. All discussions of the reproductive cycle are estimated because the topic has not been studied. It is agreed that the southern Tibetan macaque usually gives birth once every 2 years. The low ratio of infants to adults observed in the southern Tibetan macaque population may indicate that they are not annual breeders. The two-year fertility period could explain this difference. All macaques give birth to one or two young at a time, and the southern Tibetan macaque is no exception. Gestation periods vary in other macaques, but are generally between 150-190 days. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the duration of pregnancy in the southern Tibetan macaque is similar. Parental care in the southern Tibetan macaque has not been formally described. However, some strong inferences can be made based on the behavior of related species. All primates have young that are largely dependent on parental protection. In macaques, this protection is provided by the mother, who cares for the infant during the first few weeks of life. The macaque mother is also responsible for the feeding, grooming, learning, and protection of the infant. In some macaque species, other individuals also play the role of young caregivers. These may include the mother's older daughter or unrelated "aunts". Sex also sometimes contributes to parental care, taking turns holding and protecting the infant (Theirry, 2007). It is not clear whether males play any parenting role in the southern Tibetan macaques, or whether "aunting" occurs, but such behavior is possible and worthy of investigation.

The lifespan of the southern Tibetan macaque has never been studied. However, it is likely to follow the pattern of its relatives. Most species in the genus Macaca live 20 to 30 years in the wild. In captivity, many potential threats are eliminated, allowing them to live longer. Captive individuals may reach 35 years, and sometimes even 40 years.

The animals are sometimes killed by humans in retaliation for their crop destruction. However, in general, locals do not eat primates. Some primate hunting is carried out by non-local government employees. According to Sinha et al., 54 macaques were killed in a village in the West Kameng district in 2006 over a period of more than a year. There is not much habitat loss within its range.

According to reliable sources, 35 different populations are known, with at least 569 different members (32 of which are in Tawang with 540 individuals, and 3 of which are in Sikkamen, Kumar, etc. with 29 individuals). However, another source has the number of mature individuals as less than 250 individuals.

Although this is a newly described species, it is listed in Appendix II of CITES for conservation. Sinha et al. (2005) recommend the establishment of community awareness and conservation programs, and the designation of locally appropriate protected areas. It is not known whether this is the case in any official protected area, but it is likely to occur in the Muling National Park, but confirmation is needed.

Listed in the 2008 Red List of Threatened Species of the World Conservation Union (IUCN) ver 3.1-Endangered (EN).

Listed in Appendix I, II and III of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) 2019 Edition Appendix II.

Listed in the second level of China's National Key Protected Wildlife List (February 5, 2021).

Protect wild animals and stop eating game.

<p style="text-indent: 2e