Nomascus concolors

IUCN

LCBasic Information

Scientific classification

- name:Nomascus concolors

- Scientific Name:Nomascus concolors, Black Crested Gibbon、Black Gibbon、Concolor Gibbon、Indochinese Gibbon、Western Black Crested Gibbon, Gibbon Noir, Gibón de cresta negra, Westlicher Schopfgibbon

- Outline:Primates

- Family:Hylobates B.Gibbon

Vital signs

- length:43-54cm

- Weight:7-8kg

- lifetime:30-40years

Feature

The western black-crested gibbon has the longest arms relative to its body size of all primates.

Distribution and Habitat

Distributed in China (Yunnan), Laos and Vietnam. Historically recorded in Guangxi, China, and even as far as the Yangtze River Three Gorges area, it is now only found in Yunnan, with a sporadic distribution.

As a whole, it occurs discontinuously in southwestern China, northwestern Laos and northern Vietnam. A thousand years ago, the western black-crested gibbon was distributed in most of southern and central China, all the way to the Yellow River basin.

The nominate subspecies is distributed in southern China (central and southwestern Yunnan) and northern Vietnam (Lao Cai, An Bai, Son La and Lai Chau provinces). It is located between the Salween River (Nujiang) and the Red River, at 23°45'N and about 20°N (Groves 2001). The Laotian subspecies occurs in northwestern Laos. It is an isolated population, and the species is only found in a small area on the east bank of the Mekong River at about 20°17'-20°25'N (Groves 2001).

It mainly lives in tropical rain forests a

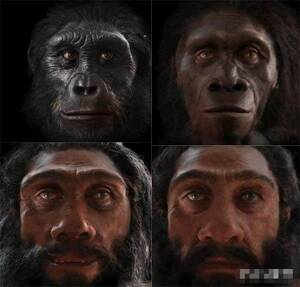

Appearance

The Western Black-crested Gibbon is a medium-sized ape with a sturdy body. The head and body are 43-54 cm long; the hind legs are 15-16.5 cm long; the total skull length is 9-11.5 cm; and the weight is 7-8 kg. Males are completely black; females are yellow, orange or light brown, with a black crown and usually black spots on the chest and abdomen. Both males and females have a light black hairless face and a prominent hair crown on the top of the head. Both males and females have no tails and cheek pouches. The dark crown spots of females of different subspecies are different in shape: the nominate subspecies is a small diamond shape; the ones distributed in Wuliang Mountain are round with a drooping neck line; and the ones distributed in southwest Yunnan have a large spot on the entire head crown and a neck strap.

Compared to the body size of all primates, the Western Black-crested Gibbon has the longest arms. The arms of the Western Black-crested Gibbon are about twice the length

Details

The Western Black Crested Gibbon (scientific name: Nomascus concolors) is known as Black Crested Gibbon, Black Gibbon, Concolor Gibbon, Indochinese Gibbon, Western Black Crested Gibbon, Gibbon Noir in French, Gibón de cresta negra in Spanish, and Westlicher Schopfgibbon in German. It has two subspecies. Before 1986, the western black-crested gibbon was considered to have four subspecies (N.c.concolor, N.c.furvogaster, N.c.jingdongensis and N.c.lu). However, in 2010, through DNA identification, the subspecies (N.c.furvogaster) distributed in southwestern Yunnan and west of the Mekong River and the subspecies (N.c.jingdongensis) distributed in the Wuliang Mountain area of Jingdong in central Yunnan were considered synonymous with the nominate subspecies, while the subspecies (N.c.lu) was still considered a valid subspecies (Thinh et al. 2010).

In China, dwarf forests serve as corridors for the movement of western black-crested gibbons. The average group size of this species also appears to vary greatly by region or study; most groups in Wuliang Mountain have two breeding females per group. In Laos, based on observations of five groups of western black-crested gibbons, the average group size was determined to be between 3.6 and 3.8 individuals. Chinese groups occupy large home ranges, with observations of 151 hectares, 260 hectares and >100 hectares (Fan and Jiang 2008). A group of studies in Dazhaizi, Wuliangshan, showed that daily travel distances ranged from 300-3,144 meters, with an average of 1,391 meters, which was related to the abundance of fruits and leaves. In some months, travel distances were lower, that is, fruit utilization was low (Fan and Jiang 2008). The activity area is relatively fixed, and there is no seasonal migration. The activity range of the western black-crested gibbon community is mostly around 60 hectares, which is much larger than other gibbons, and the population density is 2.6 individuals/km2.

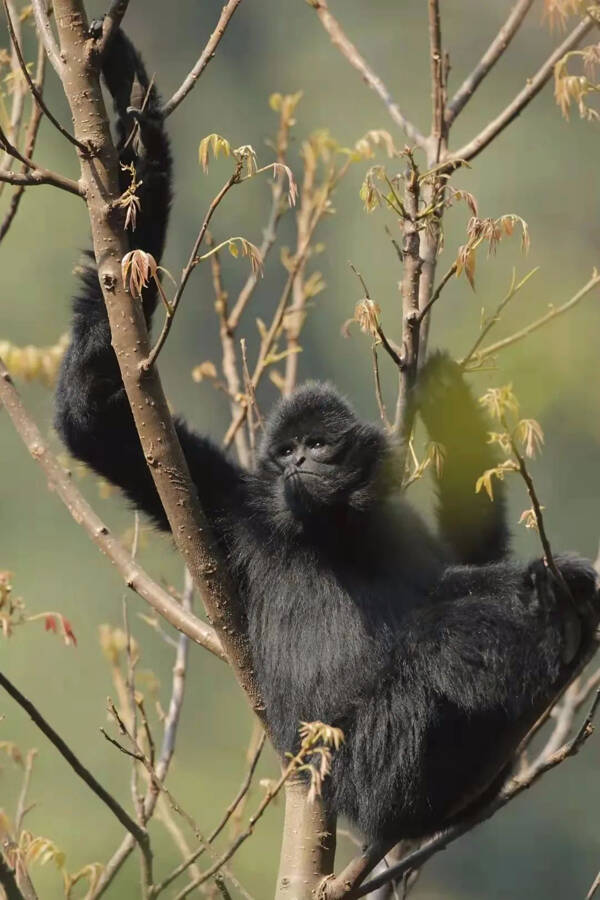

The western black-crested gibbon moves from one tree to another through a form of arboreal locomotion called arm-reaching, in which the western black-crested gibbon uses only their long arms to support their weight and swings from one branch to another. Only a few other apes and monkeys have adapted this unique form of locomotion. The Western Black-crested Gibbon is a master of stretching, reaching distances of up to 15 meters in the air and speeds of up to 56 km/h.

The Western Black-crested Gibbon is a family-based animal, living in small family groups consisting of an adult male and female and up to 5 offspring. A gibbon family searches for new food sources within its habitat every day. Sexually alert, active at dawn and dusk, with a fixed range and activity routes. Arboreal, climbing freely, rarely coming to the ground. Sleeping curled up in trees, sometimes lying on their backs on large tree trunks. Spending most of the time in tall trees in the canopy. It is diurnal, sleeping in tall, dense trees near food sources.

The Western Black-crested Gibbon is active during the day. When active, it rarely goes to the ground, and rarely climbs on trees with its forelimbs. Almost all activities are done by climbing on branches with its forelimbs, or swinging between branches. It can be said that it jumps in the air, and its long arms can climb freely. When swinging, it only needs to use the four fingers of its forefoot to grasp and leap over, without using the thumb to grasp. But when climbing trees, it needs to use the thumb. It never builds a nest, but only rests in dense leaves. The resting posture is very interesting, like a person squatting on the ground, with the forelimbs hugging the knees, and the face against the chest and knees. In this way, the thick fur on the body is impervious to rain and keeps warmer. Sometimes it will lie on its back on a large tree trunk. Only when looking for food will it climb to the high tree crown or climb into the bamboo forest bushes.

The Western Black-crested Gibbon communicates mainly through vocalization, but also through physical interaction and facial expressions. Every sunrise, the eye-catching monkey cry can often be heard in the morning light, "Hu-Hu-Hu, Hu, Hu", clear and loud, one after another; sometimes mixed with the low response sound "Wu-Wu", interlaced and noisy. The duets of paired Western Black-crested Gibbons are structurally stable, male-dominated, and highly gender-specific—there is no overlap in pitch or syllables between the two sexes. Although gibbon song is genetically determined, with each species having a fixed song pattern, it can also show some plasticity as the environment changes, which is reflected in individual differences. The discovery (2015) that Western Black-crested Gibbons have a complex language (close calls) revolutionized scientists' views on the origins of human language. For example, gibbons can communicate the type of predator that is approaching, the distance of the threat, and whether it is moving or standing in one place.

Western Black-crested Gibbons are known for their distinctive loud, complex, siren-like vocalizations. Songs are usually heard at dawn; however, season and weather appear to affect the timing, frequency, and duration of singing. Elaborate vocalizations serve a variety of purposes, including reinforcing pair bonds, attracting mates, and establishing family territories. In the morning before feeding, the gibbons can be heard calling out solo or in duets between males and females. These calls are made from the treetops with individual notes and very delicate tunes. The unique notes in the calls allow researchers to distinguish between the sexes and different species of the western black-crested gibbon. Each subspecies and even each family has its own vocalization pattern and notes.

Although the western black-crested gibbon also eats buds, leaves, bark, flowers, small vertebrates, insects and eggs, most of their food is high in sugary fruits such as figs. They do not drink much water, relying mainly on the moisture in their food, or licking the dew on the leaves after rain, and only occasionally going down to the ground to drink water during spring droughts. The feeding ecology of this species is 46.5% leaves, 25.5% fruits, 18.6% figs, 9.1% flowers, and 0.3% others. They are also reported to feed on gray-backed flying squirrels, bird eggs, small birds and lizards.

The social mating system of the Western Black Crested Gibbon is "one male and multiple females", usually consisting of one adult male and two adult females. Only small groups that are disturbed are "one male and one female". One litter per year, one cub per litter. The calving season is around May-June of each year. The calving period is 2-3 years apart. The gestation period lasts about 7-8 months. The pups are born with white fur. For the first few months, the pups cling to the female's abdomen while the mother swings around the canopy. The fur color of the pups, regardless of sex, slowly changes from white to gray around 1 year old, eventually turning completely black. Females nurse the pups until 2 years old, during which time males and older offspring also provide pup care. The pups' fur color remains black and only changes when they reach sexual maturity at 7 or 8 years old. Therefore, it is impossible to distinguish the sex of subadults from their color. When reaching sexual maturity, females change from black to yellow-beige, and both males and females leave their native families. It is estimated that sexual maturity occurs at 6-7 years old, with a lifespan of 30-40 years.

The greatest threats to the Western Black-crested Gibbon throughout its range include destructive local forest use and hunting, while selective logging and agricultural encroachment are additional threats (Geissmann et al. 2000; Jiang et al. 2006; Sun et al. 2012; Wei et al. 2017). In Laos, despite local taboos against hunting Western Black-crested Gibbons in some areas (Geissmann 2007; Rawson et al. 2011; Youanechuexian 2014), these animals are captured and killed for subsistence and for the pet and “medicine” trade. Hunting and development activities such as the Asian Development Bank-funded infrastructure and Highway 3 through Nam Kan pose additional threats. In Vietnam, depending on the location, these gibbons are primarily threatened by human impact on habitat and hunting pressure, but ultimately always a combination of both. Other issues such as forest fires and hydropower construction threaten the population of some species in Vietnam (Rawson et al., 2011).

Listed in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2015 ver3.1 - Critically Endangered (CR).

Listed in Appendix I, Appendix II and Appendix III of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) 2019 edition.

Listed in China's National Key Protected Wildlife List (February 5, 2021) Level 1.

Protect wild animals and stop eating game.

Maintaining ecological balance is everyone's responsibility!