Hyperoodon ampullatus

IUCN

LCBasic Information

Scientific classification

- name:Hyperoodon ampullatus

- Scientific Name:North Atlantic bottlenose whale, flathead whale, bottlehead whale, steep-headed whale

- Outline:Cetacea

- Family:B.whales

Vital signs

- length:7-9m

- Weight:5.8-7.5 tons

- lifetime:About 37 years

Feature

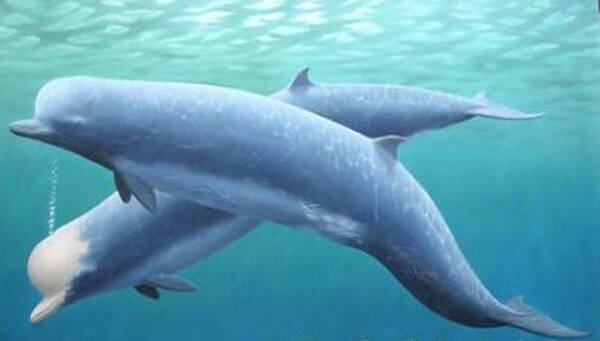

The body is long but chubby, with a prominent beak and a towering forehead.

Distribution and Habitat

The Northern Bottlenose Whale is found only in the North Atlantic Ocean, mainly in the cold temperate waters of the subarctic region. In the western Atlantic Ocean, it mainly inhabits the Davis Strait and the northern Labrador Sea, as well as the waters north of Nova Scotia, Canada, called "The Gully". In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, it is located in Greenland, the Arctic Sea and the Barents Sea. As for the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Hudson Bay, the North Sea, and the Baltic Sea, it is less common. There have been several reports of sightings of the Northern Bottlenose Whale in the northern North Pacific Ocean, which are presumably Baird's Beaked Whale.

The Northern Bottlenose Whale prefers deep waters over 1,000 meters deep, and occasionally appears in seas with floating ice. Their movements are complex, and they do not seem to follow the general migration principle of large whales, "north in summer and south in winter." Northern bottlenose whales appear seasonal

Appearance

Length and weight at birth: 3-3.5m, maximum length and weight recorded: male - 9.8m, female - 8.7m; weight 5,800~7,500kg, life span: at least 37 years

The pectoral fin is small and straight, with a rounded end, and there is no indentation in the center of the caudal fin. The gender can be distinguished by the appearance of the head. The adult male whale has a white forehead and is convex to nearly square, while the female whale has a grayer and spherical forehead (the immature male whale is somewhere in between). There are two teeth at the tip of the lower jaw. Usually only the teeth of adult male whales grow until the gums are exposed and are slightly curved forward. The teeth are sometimes attached with Minghejie (gooseneck pot). A small number of male whales may have four teeth or remain toothless throughout their lives.

The body color of adult whales is gray to brown on the back and lighter on the abdomen; the body color of juvenile whales is darker than that of adult whales,

Details

The scientific name of the northern bottlenose whale is Hyperoodon ampullatus. In 1770, Forster first mentioned the northern bottlenose whale in the translation notes of "Kalm, Travels into North America". The scientific name at that time was "Balaena ampullatus". The species name comes from the Latin ampulla, which means "bottle" or "flask", reflecting the shape of its beak, and has been used ever since. In 1776, Müllar changed the name to Balaena rostrata. After being transferred to the genus of bottlenose whales, it was called Hyperoodon rostrata for a long time. It was not until the early 20th century that it was changed to the current effective scientific name Hyperoodon ampullatus.

Northern bottlenose whales usually appear in groups of 1 to 4 whales. More than this number is quite rare, but there have been records of up to 20. Sometimes many such independent small groups can be seen on the sea at the same time. The group usually consists only of adult female whales and calves or juvenile whales, and sometimes includes one or more adult male whales. Northern bottlenose whales are very curious animals. They will approach stationary or slow-moving ships and swim around until they are satisfied. This characteristic was first discovered and used by whalers. They would sail their boats to the waters where northern bottlenose whales often appear, then float on the sea surface and wait for them to actively approach the ships. Their surface behavior includes being stationary for a period of time, then suddenly swimming in different directions, sometimes lobtailing and breaching.

Whalers have claimed that northern bottlenose whales sometimes dive for up to two hours when harpooned, but their diving time is generally between 14 and 70 minutes, often diving to a depth of less than 800 meters, with the deepest record being 1,500 meters. After a deep dive, they usually stay on the surface for about 10 minutes, breathing every 30 to 40 seconds, and the multi-branched jet can reach 1 to 2 meters high. They do not raise their tail fins when diving, and usually surface at the same place.

Northern bottlenose whales can make discontinuous whistles, chirps, ticks, and sudden bursts, with different frequencies and durations, which may be related to foraging and communication between individuals.

Whalers have recorded that northern bottlenose whales can submerge for 1 to 2 hours, but typical dives without pressure are about 14 to 70 minutes. They may stay on the surface for 10 minutes or more, blowing every 30 to 40 seconds. The tree-like blows are about 1 to 2 meters high, slightly tilted forward, and can be seen in good weather. Whale tails have been observed hitting the waves, and extremely rare leaps have been observed hitting the waves. They may be good deep divers, but when diving, they usually do not move very far horizontally.

The superior diving ability of the northern bottlenose whale allows them to dive to the deep sea to find food. Starfish have been found in their stomachs, and it is speculated that they may find food near the seabed. They mainly eat squid and squid, among which the Gonatus genus, especially the Gonatus fabricii species, is their favorite and is their main food source. They also eat herring, Greenland halibut, chimaera, star marten, stingrays and many other fish, as well as shrimp and even aquarium/sea-cucumbers.html">sea cucumbers.

Most northern bottlenose whales give birth between spring and early summer (April to June), but newborn calves have been found in "The Gully" in August. The gestation period is about 12 months, the lactation period is at least 1 year, and the calves will stay with their mothers for about 2 years. Although past whaling data shows that female whales give birth every 2 years, the average reproductive interval may be more than 2 years. The calves have a fuzzy forehead, a rounder beak than adults, a grayish-white belly, and a black to chocolate brown back and sides.

The northern bottlenose whale is arguably the most intensively studied beaked whale by humans, in part due to the long history of whaling. In the 19th century, several British and Norwegian naturalists participated in the whaling industry, providing many detailed descriptions of the northern bottlenose whales that were captured, and the whaling industry also provided a large number of carcasses for scientific research.

The first known whaler to catch a bottlenose whale was the Chieftain of Kirkcaldy, Scotland, which caught 28 bottlenose whales in Frobisher Bay in 1852. Due to the presence of spermaceti (see sperm whale for details) in their heads, whaling began to expand in 1877. By 1891, Norway had more than 70 whaling ships operating in the North Atlantic, killing more than 3,000 bottlenose whales that year. The ships that caught bottlenose whales had a displacement of about 30 to 50 metric tons and were equipped with 4 to 6 whaling guns at the bow and stern. However, the front end of the harpoon of the whaling guns was not equipped with explosives, which was different from the whaling ships that caught large baleen whales. One bottlenose whale can produce about 1 ton of oil, and if it is a large male whale, it can reach 3 to 4 tons; an adult male whale can produce about 300 to 400 pounds of spermaceti.

In the 25 years of the late 19th century, the British and Norwegian fleets captured more than 22,000 bottlenose whales, not including many dead or seriously injured individuals that were not found. Norway continued to capture bottlenose whales until 1973, when it stopped. In that year, the British whale meat market (for pet food) was legally closed. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) abolished the capture quota for bottlenose whales in 1977 and implemented full protection. There is no doubt that whaling is the main reason for the decline in populations in some areas, especially in the northeastern Atlantic, but the exact amount of decline is hotly debated.

All populations have been conserved for more than 25 years and have shown significant recovery. According to a survey in the late 1980s, it is estimated that at least 5,000 northern bottlenose whales survive in the waters near Iceland and the Faoroe Islands. Although they have not been killed in large numbers by fishing, they may be threatened by oil and gas development near "The Gully".

In 2006, northern bottlenose whales were designated as an endangered population under the Canadian Endangered Plants and Fauna Act.

Protect wildlife and eliminate game.

Maintaining ecological balance is everyone's responsibility!