Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) is one of the most well-known fish species globally. It is native to the North Atlantic Ocean, but its unique life cycle, economic importance, and environmental significance make it a subject of fascination for marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and conservationists alike.

Atlantic Salmon belongs to the following scientific classification:

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Actinopterygii

Order: Salmoniformes

Family: Salmonidae

Genus: Salmo

Species: Salmo salar

This classification places Atlantic Salmon in the same family as trout and other salmon species, with its native habitat in the Atlantic Ocean. Atlantic Salmon are widely known for their anadromous nature, migrating from freshwater rivers to the sea and returning for spawning.The Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) is a species of ray-finned fish in the family Salmonidae. It is the third largest of the Salmonidae, behind Siberian taimen and Pacific Chinook salmon.

Atlantic Salmon have streamlined, muscular bodies that are well-adapted to their life in fast-flowing rivers and the open ocean. Their scales are silver, with a darker back and lighter sides, often with a pale belly.

Length: Adult Atlantic Salmon typically grow between 24-30 inches (60-75 cm), although larger individuals can exceed 4 feet (120 cm) in length.

Weight: The average weight of an adult is approximately 8-12 kg (17-26 lbs). However, the largest individuals can weigh as much as 30-35 kg (66-77 lbs), particularly in wild populations.

Lifespan: Atlantic Salmon typically live for 4-6 years, though some may survive longer depending on environmental conditions and other factors.

Their bright silver scales and distinct black spots on their backs make them easily identifiable. The coloration helps with camouflage in their natural habitats, aiding them in avoiding predators and stealthily hunting prey.

Atlantic Salmon are native to the North Atlantic Ocean and its surrounding rivers. They are found along the coasts of North America and Europe, including countries like Canada, the United States, Norway, Iceland, and Scotland.

Atlantic Salmon are anadromous, meaning they spend part of their life cycle in freshwater rivers and streams, and part in the saline waters of the ocean. In freshwater, they require cold, clean, oxygen-rich streams and rivers for spawning, while they migrate to the ocean for feeding, growing larger and more robust.

Atlantic Salmon are carnivorous fish, relying heavily on smaller fish, crustaceans, and invertebrates for sustenance. Their feeding habits vary depending on their environment. In the ocean, they primarily consume smaller fish such as herring, sardines, and other small schooling species. In freshwater rivers, they feed on insects and larvae.

Atlantic Salmon exhibit opportunistic feeding behavior, which means they take advantage of whatever prey is abundant in their environment. This ability to adapt their feeding habits has contributed to their widespread distribution and success as a species.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Atlantic Salmon is their migration pattern. Salmon hatch in freshwater rivers, migrate to the ocean to grow, and then return to the same river to spawn. This journey, often referred to as "salmon run," can span thousands of miles and is one of the most incredible migrations in the animal kingdom.

Freshwater to Saltwater Migration: After hatching, young salmon (called smolts) leave freshwater rivers and move into the ocean where they spend several years feeding and growing.

Return to Spawn: After 2-4 years in the ocean, adult Atlantic Salmon return to the river of their birth to spawn. The spawning journey is often exhausting, and many salmon die after spawning, although some may survive to spawn again.

While Atlantic Salmon are generally solitary in the wild, their migration brings them together in large groups. During the spawning season, however, males and females engage in complex social behaviors. Males fight for the attention of females, displaying aggressive postures and physical endurance during the mating season.

Salmon are primarily active during the cooler parts of the day or night, often feeding and swimming in the deeper, colder parts of the river or ocean. They spend most of their life in search of food, migrating, and breeding.

Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) exhibit fascinating reproductive behaviors that are integral to their life cycle. Their reproduction is influenced by a combination of genetic, environmental, and ecological factors, and their life history strategy includes both migration and spawning.

Spawning Period: The spawning period for Atlantic Salmon occurs during the late autumn to early winter months, typically from October to December. The exact timing of spawning can vary depending on environmental factors, such as water temperature and the flow of the river.

Migratory Nature: Atlantic Salmon are anadromous, meaning they migrate from the ocean to freshwater rivers and streams to spawn. This migration is one of the most well-known features of their life cycle.

Redd Formation: When Atlantic Salmon return to freshwater rivers, females create a nest called a redd in the gravel beds of the river. A redd is typically dug in the clean, fast-flowing sections of rivers, where oxygenated water can flow through the eggs after fertilization.

Female's Role: Female salmon are responsible for digging the redd by using their tails to move the gravel and create a depression in the riverbed. The female then lays her eggs into this nest.

Male's Role: Male salmon, known as bucks, fight for the right to mate with females. Once a female has laid her eggs, one or more males fertilize them externally by releasing their sperm over the eggs.

Eggs: A single female Atlantic Salmon can lay anywhere from 3,000 to 12,000 eggs, depending on her size and age. The eggs are round and pale, and they are deposited in layers within the gravel nest.

Incubation Period: After fertilization, the eggs are incubated for a period of 2-3 months, depending on water temperature. Colder temperatures slow the development of the eggs, while warmer temperatures speed up the process. The eggs hatch in early spring, around February to April, when the river temperature rises slightly.

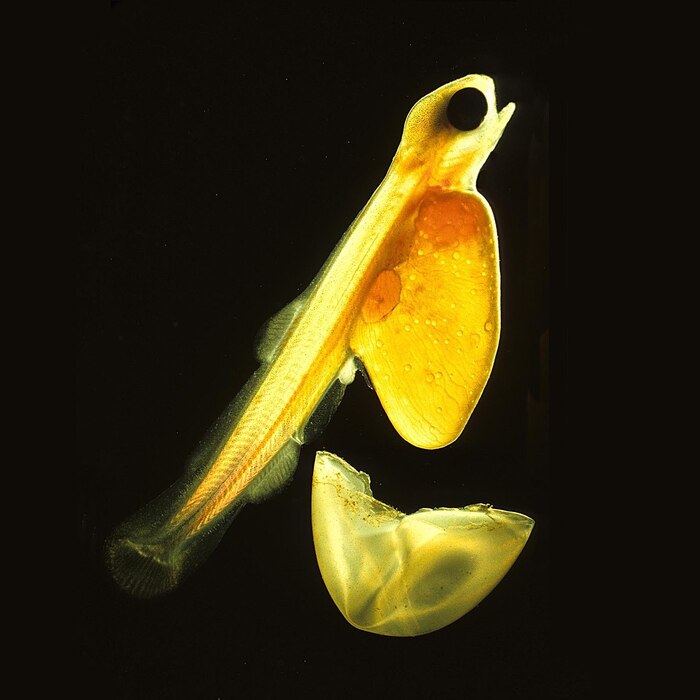

Alevins: Once hatched, the salmon are known as alevins. They remain in the gravel of the redd, surviving off the yolk sac attached to their bodies, and they are very vulnerable at this stage. The alevins will eventually begin to absorb nutrients from the river water.

Fry Development: After about 2-3 months, the alevins become fry, which are small fish that start to swim and explore their immediate environment. Fry feed on insects, larvae, and small invertebrates that live in the river.

Smoltification: As they grow, fry undergo a process known as smoltification, where they begin to adapt physiologically to life in saltwater. This process includes changes in their skin, kidneys, and the way they regulate salt, preparing them for their migration to the ocean. This is a crucial stage in the salmon’s life cycle.

Migration to the Ocean: After spending 1-3 years in the freshwater river, the young salmon (now called smolts) begin their migration to the ocean, where they will grow and mature. This migration is one of the most impressive feats of nature, as the salmon travel hundreds or even thousands of miles to reach the rich feeding grounds of the North Atlantic.

Feeding and Growing: In the ocean, Atlantic Salmon feed on smaller fish and invertebrates. They grow rapidly in the nutrient-rich waters of the ocean, developing their characteristic size, strength, and silvery appearance.

Maturity: Atlantic Salmon typically reach sexual maturity at 2-4 years of age. They are considered mature and ready to spawn after they have spent enough time feeding and growing in the ocean.

Return to Freshwater: After spending 2-4 years in the ocean, Atlantic Salmon return to their natal river to spawn. This return migration is triggered by environmental cues such as changes in water temperature, daylight hours, and instinctual patterns that drive them back to the river where they were born.

Spawning Cycle: When they reach their spawning grounds, males and females engage in spawning, repeating the cycle. After spawning, many of the adult salmon die, though some individuals may survive and return to spawn in subsequent years, a behavior known as repeat spawning.

Natural Death: After spawning, most Atlantic Salmon die, which is a natural part of their life cycle. Their bodies contribute organic material to the river ecosystem, enriching the environment for other species.

Repeat Spawning: Although most salmon die after spawning, some survive and make the return trip to the ocean to repeat the cycle. These repeat spawners are typically females and are known to produce more eggs than first-time spawners.

Maturation and Migration: Adult Atlantic Salmon spend several years in the ocean before returning to freshwater rivers to spawn.

Spawning: Females lay eggs in a redd (nest) created in the riverbed, and males fertilize the eggs externally.

Eggs Hatch into Alevins: The fertilized eggs incubate for 2-3 months before hatching into alevins.

Growth to Fry: The alevins develop into fry, which then undergo smoltification to adapt to life in saltwater.

Migration to the Ocean: The young salmon (smolts) migrate to the ocean, where they mature over several years.

Return Migration: Mature salmon return to their natal rivers to spawn, completing the cycle.

Post-Spawning Death: Most adults die after spawning, although some may return to spawn multiple times.

This reproductive process allows Atlantic Salmon to ensure the survival of their species, though challenges such as habitat loss, pollution, and overfishing continue to impact their populations.

The Atlantic Salmon is classified as Endangered or Vulnerable in many regions due to habitat loss, pollution, overfishing, and the impact of climate change. Populations have been dramatically reduced in both the wild and farmed environments, making conservation efforts crucial.

Efforts to protect Atlantic Salmon include habitat restoration, regulation of fishing practices, and initiatives to combat river pollution. Several international and regional organizations are working to monitor populations and ensure sustainable fishing.

Commercial fishing and recreational fishing, while heavily regulated in many areas, still pose a significant threat to wild Atlantic Salmon populations.

Pollution from industrial waste, agricultural runoff, and urban development has degraded water quality in rivers and oceans, negatively impacting salmon health and reproduction.

Warmer water temperatures and changes in ocean currents due to climate change are disrupting salmon migration and spawning patterns, threatening their survival.

Atlantic Salmon is one of the most economically important fish species globally. It is widely farmed in aquaculture, with Norway, Chile, and Scotland being major producers. The demand for Atlantic Salmon has increased significantly due to its high nutritional value, making it a staple in many markets.

Global Harvest: In 2021, global harvests of farmed Atlantic Salmon were estimated at over 2.5 million tons.

Wild Salmon Fisheries: While wild Atlantic Salmon fishing remains vital in many regions, farmed salmon accounts for the majority of the salmon consumed worldwide.

Farmed Atlantic Salmon is often more affordable than wild-caught salmon, making it accessible to consumers globally. However, wild-caught salmon, due to its rarity and environmental factors, tends to be priced higher.

The Atlantic Salmon is a species with deep cultural, ecological, and economic significance. Despite the challenges they face due to overfishing, habitat degradation, and climate change, efforts to protect and conserve Atlantic Salmon populations are essential to maintaining biodiversity and ensuring a sustainable future for this iconic fish species. The careful management of wild and farmed salmon populations will be key to ensuring that Atlantic Salmon remain a thriving part of our oceans and rivers for generations to come.

The annual catch of Atlantic Salmon is substantial, particularly in aquaculture, with global production estimates of 2.5 million tons of farmed salmon. Different varieties are classified based on region, farming methods, and size, with wild-caught Atlantic Salmon fetching the highest market prices due to its scarcity. These factors, combined with the fish’s high economic value, make it a key player in global seafood markets.

animal tags: salmonidae

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.