The narwhal (Monodon monoceros), often called the “unicorn of the sea,” is one of the Arctic’s most fascinating and mysterious marine mammals. Belonging to the small Monodontidae family—which includes only the narwhal and the beluga—the narwhal stands out for its unique appearance and remarkable adaptations. In this article, you’ll discover the key characteristics of narwhals, where they live, what they eat, their reproductive habits, and their current conservation status.

Famous “Unicorn” Tusk: The narwhal’s “horn” is actually a long, spiraled tooth (usually the left canine) that extends from the upper jaw, mainly in males, and can reach up to 3 meters (about 10 feet) long. Females rarely have a visible tusk.

Size and Color: Adult narwhals measure between 3.8 and 5 meters (12.5–16.5 feet) long. Their skin is mottled brown and gray, becoming lighter on the belly. The body pattern becomes more complex with age.

Head and Echolocation: Narwhals have rounded heads with a prominent organ called the “melon,” used for echolocation—helping them navigate and hunt in dark, icy waters. Their foreheads are squared and their snouts are reduced.

No Dorsal Fin: Unlike most whales, narwhals lack a dorsal fin, an adaptation that helps them maneuver beneath Arctic ice sheets.

Breathing and Diving: Narwhals have a blowhole on their back for breathing and are expert divers, able to stay submerged for up to 3 hours and dive as deep as 1,500 meters (nearly 5,000 feet).

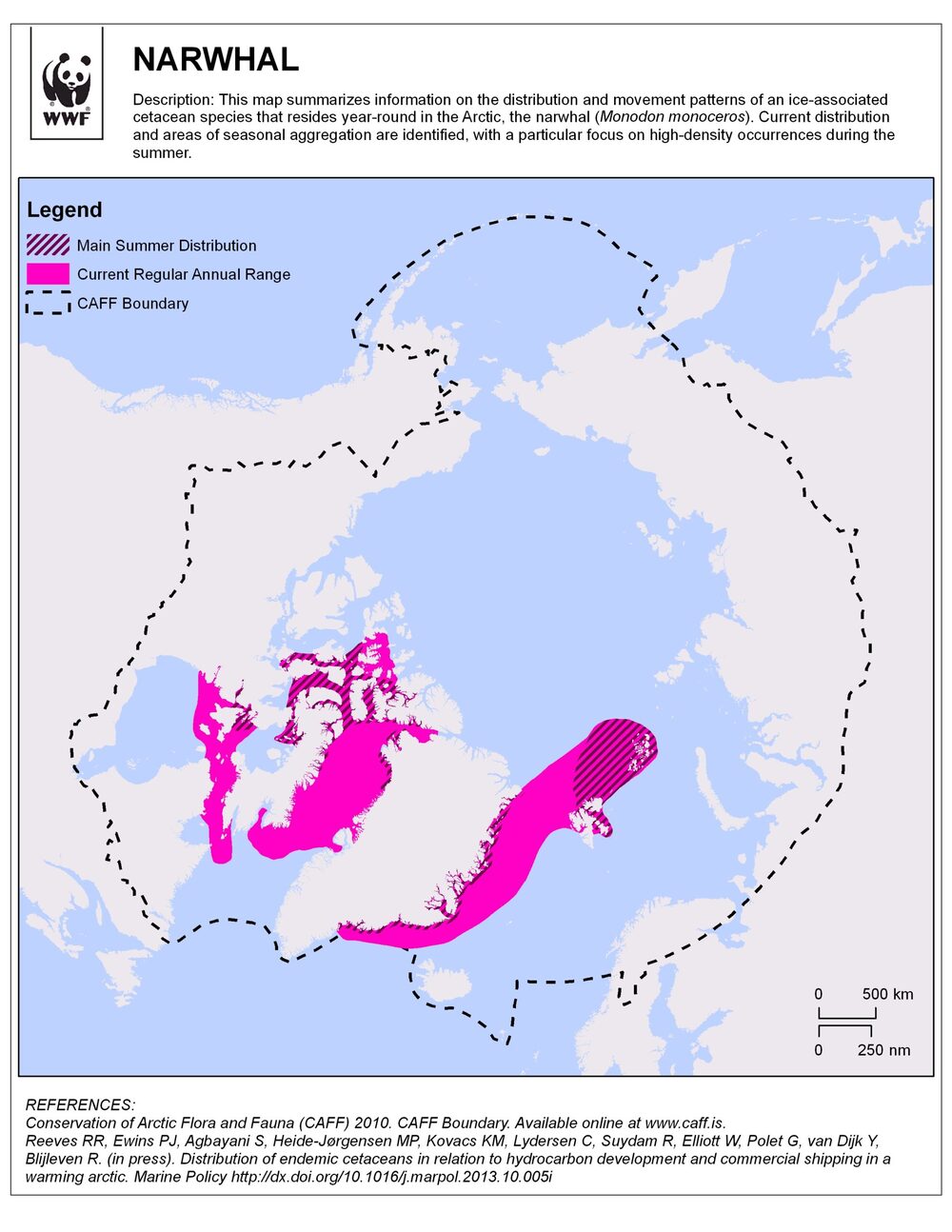

Narwhals inhabit Arctic waters in the Northern Hemisphere, primarily:

Canadian Arctic Archipelago

Eastern Baffin Island

Svalbard (Norway)

Northern Russia

Eastern Greenland

Some populations are migratory and may occasionally reach as far as Germany, Iceland, Norway, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the northern United States. Narwhals prefer deep, ice-covered waters along the edges of continental shelves and are well-adapted to surviving in regions with heavy sea ice. There are about 12 genetically distinct subpopulations due to geographic isolation.

Narwhals are highly social, usually living in groups. In winter, they form large herds of several hundred individuals, while in summer, they split into smaller groups of about ten. The exact purpose of the tusk is still debated, but most scientists believe it is used for social dominance among males and may also help stun or spear prey.

Narwhals are carnivorous and rely heavily on Arctic marine life:

Main Diet: Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides), Arctic cod (Boreogadus saida), polar cod (Arctogadus glacialis), squid, and shrimp.

Foraging Behavior: They hunt mostly benthic (bottom-dwelling) prey during the winter, and are more opportunistic in the summer.

Echolocation: Narwhals use echolocation, emitting high-frequency sounds through the melon to locate prey in dark or murky waters.

Viviparous Mammals: Narwhals reproduce via internal fertilization; females give birth to live young after a gestation period of about 15 months.

Sexual Maturity: Narwhals reach sexual maturity at 6–9 years old. The mating season occurs in March, and calves are typically born between June and August.

Calf Rearing: Mothers nurse their calves for about 20 months, teaching them vital survival and hunting skills during this period.

According to the IUCN Red List, the narwhal is currently classified as Least Concern, with an estimated 123,000 mature individuals in the wild. However, several threats remain:

Habitat Loss: Melting sea ice, ocean pollution, and new diseases threaten narwhal populations.

Hunting: While narwhals were heavily hunted in the early 20th century, today only a limited number are hunted by Indigenous peoples in Canada and Greenland, primarily for subsistence and traditional use.

Trade Restrictions: Narwhal ivory (tusks) is strictly regulated to prevent illegal trade.

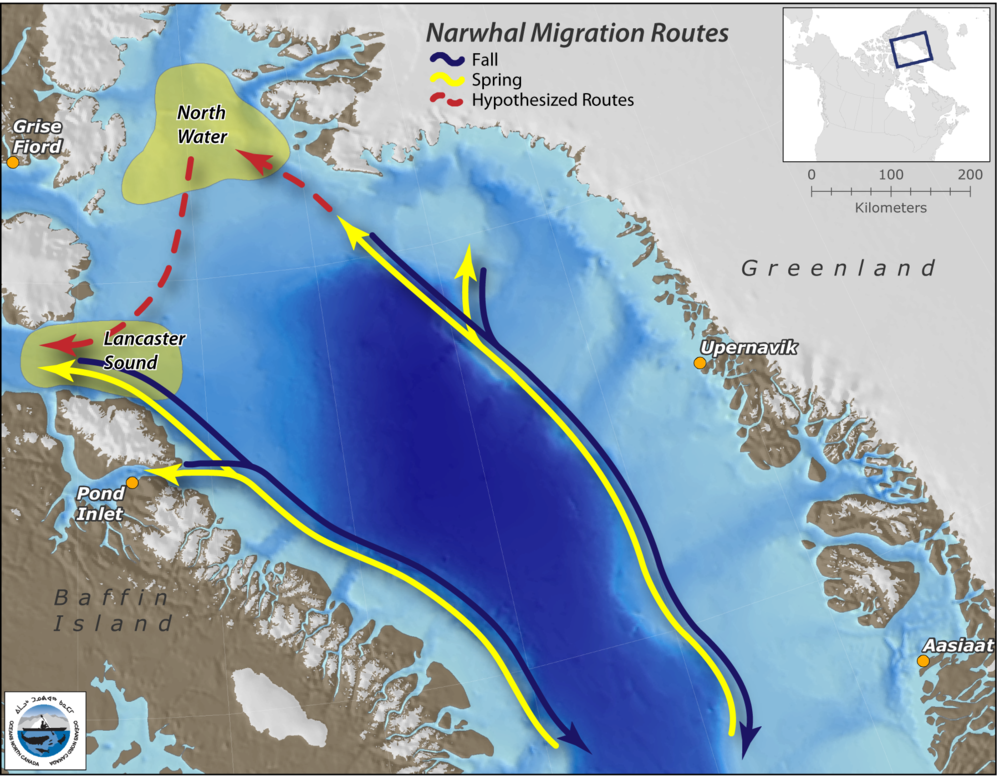

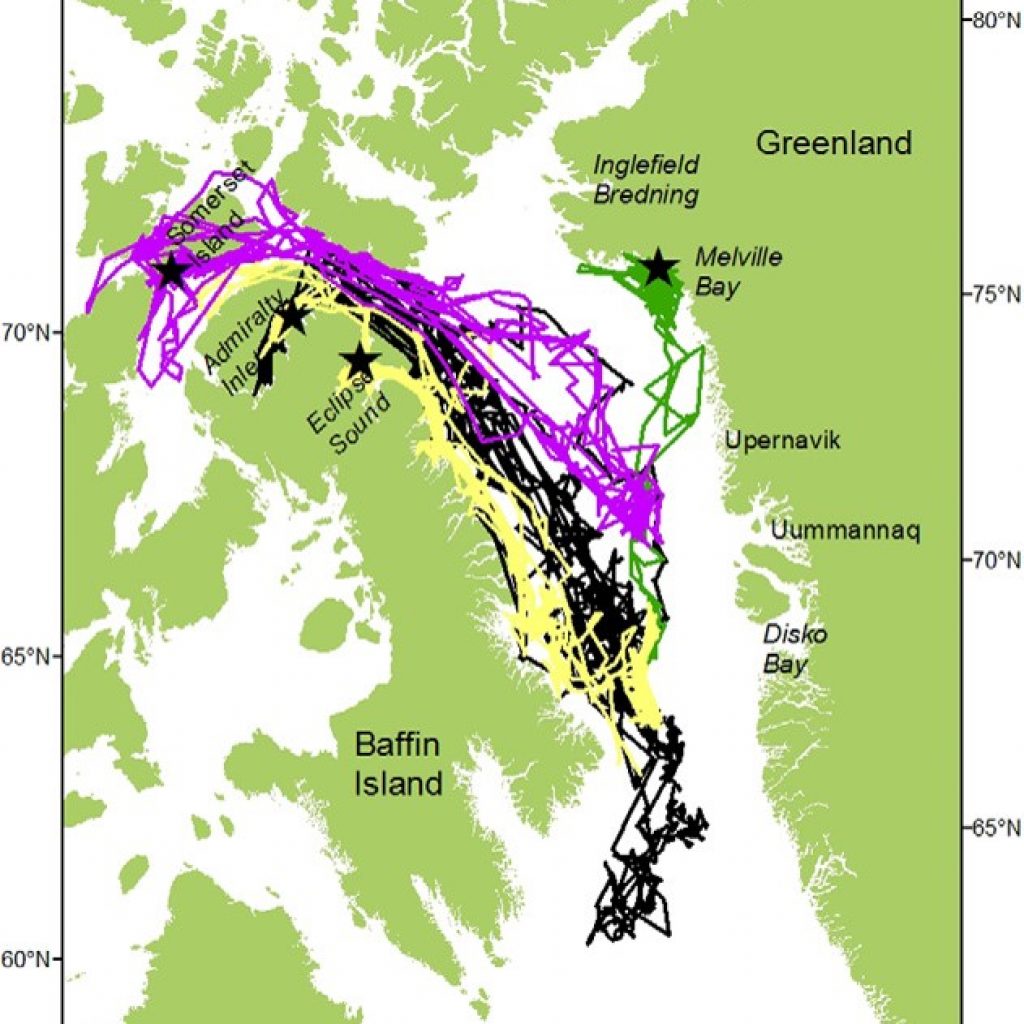

Narwhal (scientific name Monodon monoceros) mainly inhabits the Arctic Ocean. Its migration route shows a typical cycle of moving from the deep winter waters back to the shallow ice edge waters in spring and returning to the outer sea of the ice zone in autumn. The annual journey can reach more than 3,000 kilometers.

They choose migration routes along fjords and fjords, with stops for several days to weeks along the way to forage and rest.

They choose open deep waters as their migration routes, which are more direct, longer, and have fewer stops, but they also achieve energy minimization.

This multi-strategy migration pattern shows that individuals flexibly weigh resources and energy consumption, and may also form cultural habits that are passed down from generation to generation.

Spring (May-June): As the ice melts, narwhals move from deep waters in the ice to shallow straits such as Lancaster Sound, using cracks to enter and exit for mating and social activities.

Summer: They live in shallow waters near the ice and feed on fish around cracks in the ice .

Autumn (September-October): Migrate to the deep waters of Davis Strait and Baffin Bay to spend the winter.

These routes form a critical migration corridor that scientists call the "Blue Corridor".

| Threats | Impacts |

|---|---|

| Sea ice shrinkage | Disturbance of stay and migration channels |

| Ship noise and traffic | Interference with sonar positioning and behavior, forcing whales to change course |

| Resource extraction (oil and gas) | Reduced habitat safety and ecological integrity |

Therefore, scientists and conservation organizations recommend:

Identify and protect migration stopovers and corridor areas;

Develop ship speed limits and route avoidance guidelines;

Integrate regulatory cooperation across borders to cover the Arctic region’s blue corridors.

Narwhals adopt a spring and autumn round-trip migration of thousands of kilometers, and cleverly combine direct ocean migration and near-shore replenishment strategies;

Ice dynamics and human activities have a significant impact on their migration;

Protecting migration routes and key stopovers is critical to mitigating climate and industrial interference.

With their iconic spiral tusk and Arctic adaptations, narwhals are truly unique among marine mammals. Although they are not currently considered endangered, climate change and human activities continue to pose risks. Ongoing scientific research, conservation efforts, and international protection are essential for the narwhal’s future.

References

Lowry, L., Laidre, K. & Reeves, R. (2017) Monodon monoceros. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/13704/50367651.

Bibliography

Beatty, R., Beer, A., & Deeming, C. (2010). The Book of Nature. Great Britain: Dorling Kindersley.

animal tags: Narwhal

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.