Recently, Nature Ecology & Evolution, a subsidiary journal of Nature magazine, published a study independently completed by the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences on the independent evolution of the skull and body of early birds. Li Zhiheng and Wang Min are the co-first authors, and Wang Min is the corresponding author. Nature Ecology & Evolution is in the first area of the Biology Category of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, IF: 15.46.

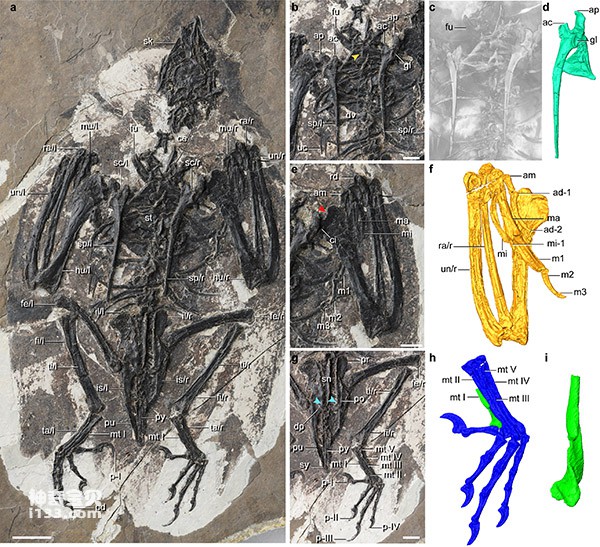

The Mesozoic Era records how birds evolved from dinosaurs and developed unique body characteristics. The diversity of bird lineages at this stage of evolution is mainly dominated by ornithorax, which is composed of enantiornithes and modern ornithomorphs. Ornithorax has evolved a large number of morphological characteristics similar to those of living birds, which are similar to the most primitive birds. Birds (Archaeopteryx) vary greatly in morphology. Non-ornithothoracic birds (hereinafter referred to as basal birds) with an evolutionary position between the two provide important information to fill this gap. However, the discovery of fossils has long limited the research on the early differentiation of basal birds. The bird discovered this time happens to belong to a new genus and species of Jinguofortisidae, the basal bird of the Jehol Biota (135-120 million years ago) (Figure 1). The researchers named it Zhu's Craton Bird of Prey (Cratonavis zhui): Bird of prey, meaning a ferocious bird, is taken from Qu Yuan’s "Li Sao" - birds of prey are not gregarious, which has been established since the past life; the genus name Craton is taken from the National Natural Science Foundation of China Basic Science Center Project " Craton Destruction and Terrestrial Biological Evolution" (this is a large-scale interdisciplinary project exploring the intrinsic relationship between biological evolution and the destruction of the North China Craton). The species name is dedicated to Academician Zhu Rixiang, whose team has conducted a lot of important research on the mechanism of destruction of the North China Craton.

The skull morphology of cratonic grebes and theropod dinosaurs is almost the same. In particular, the structure of the bitemporal foramina of primitive archosaurs is retained—the upper and lower temporal foramina are independent of the orbit and separated from each other. The wing bones have enlarged square bone branches. The vomer is thick. These primitive characteristics indicate that the cratonic grebe has not evolved the skull mobility that most living birds have, that is, the upper jaw moves independently of the brain and lower jaw. In contrast, the cratonic grebe's postcranial skeleton already possesses a large number of advanced bird characteristics, such as an ossified sternum, elongated forelimbs, shortened tailbone, and opposable paws, etc., illustrating the modular evolution of the skull and body. , the skull, especially the temporal and palatal regions, are evolutionarily conservative.

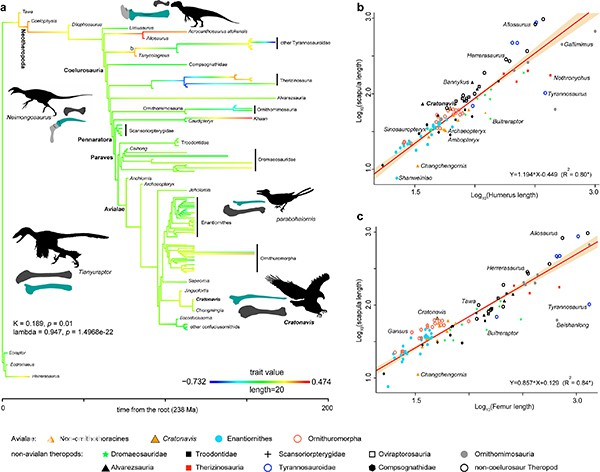

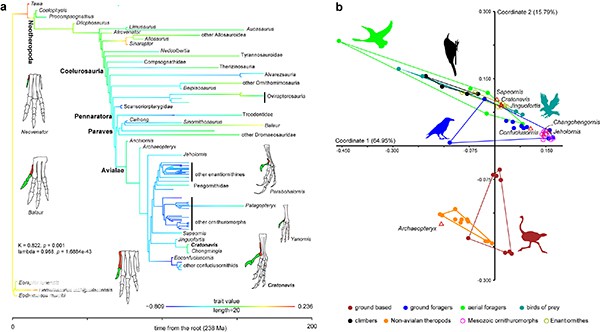

The most unique thing about Craton's grebe is its unusually long shoulder blade and first metatarsal (equivalent to the innermost bone of the foot). Through the method of comparative cladistics, the researchers traced the dynamic trajectory of the above two bones in the evolution of dinosaurs and birds (Figure 2). The scapula is an important part of the bird's flight structure, and its shape varies significantly among birds with different flight modes. The researchers found that the length of the scapula is more likely to change in theropod dinosaurs than in birds. Its independent lengthening in Craton's grebe may be an attempt to adapt to flight, because the lengthened scapula can expand the control of downward flapping of the wings. The attachment area of the muscle. The relative length of the first metatarsal of the cratonic grebe is much greater than that of other birds and most dinosaurs. In the evolution of dinosaurs and birds, the first metatarsal shows a trend of shortening. For example, the relative length ratio of the first metatarsal in birds is much smaller than that of primitive theropod dinosaurs, while the ratio of the first metatarsal in birds is smaller than that of the first metatarsal in birds. The difference has been established since the beginning. The lengthening of the first metatarsal in cratonic grebes is the result of independent evolution. This conclusion is also confirmed by changes in the phylogenetic signal of the first metatarsal: its degree of influence by phylogenetic relationships is higher in theropods but decreases as one approaches parabirds (Fig. 3). Using ecological spindle analysis, combined with the huge first toe and curved claws, the researchers proposed that the abnormal growth of the first metatarsal may be related to the raptor-like ecological habits of the cratonic grebe. The unique scapulae and metatarsals of Craton's grebe show that under the dynamic effects of ontogeny, natural selection and ecological functional opportunities, some bones that appear to be relatively conservative in evolution "break away from the constraints" and undergo evolutionary changes.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Basic Science Center Project "Cratonic Destruction and Terrestrial Biological Evolution", the Chinese Academy of Sciences Frontier Science Key Research Program from "0 to 1" Original Innovation Ten-Year Merit Project, and the Tencent Discovery Award.

Paper link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-022-01921-w

Figure 1: The holotype specimen of Cratonavis zhui (Photo courtesy of Wang Min and Li Zhiheng)

Figure 2: The evolutionary trajectory of the scapula during the evolution of dinosaurs and birds (photo provided by Wang Min)

Figure 3: The evolutionary trajectory of the first metatarsal bone during the evolution of dinosaurs and birds (photo provided by Wang Min)

Figure 4: Zhu’s Craton bird of prey restoration map (drawn by Zhao Chuang)

animal tags:

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.