Fish are among the oldest and most diverse vertebrates on Earth, with reproduction strategies that are as fascinating as they are varied. From external fertilization to mouthbrooding, sex-changing behaviors, and even asexual reproduction, the ways fish propagate their species are deeply shaped by their environments and evolutionary histories. As an animal expert, this article explores the biological, behavioral, and ecological dimensions of fish reproduction in detail.

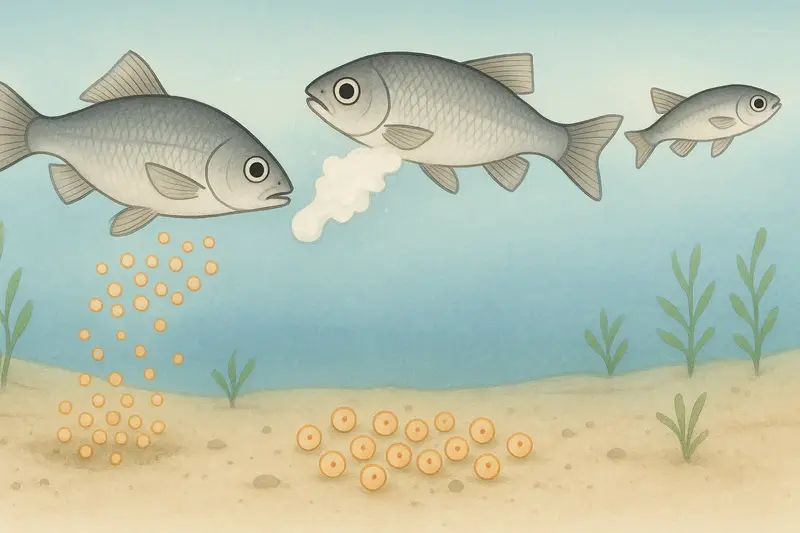

Most fish reproduce through external fertilization, where females release eggs into the water and males simultaneously release sperm to fertilize them. This method is common in species like carp, goldfish, and bass.

Some species, such as guppies, sharks, and rays, use internal fertilization. Males have specialized reproductive organs (e.g., claspers) to deliver sperm directly into the female.

Oviparous fish lay fertilized eggs externally, which hatch in the environment (e.g., crucian carp).

Ovoviviparous fish develop embryos inside the mother, nourished by the yolk but born live (e.g., guppies).

Viviparous fish provide direct nourishment from the mother to the embryo, as seen in some sharks.

Male fish may change color, perform swimming dances, or make sounds to attract mates. For example, bettas display flared fins, and male goldfish chase females as part of courtship.

Species like bass, koi, and dace create nests by digging pits or weaving aquatic plants to provide a safe place for egg laying and hatching.

Some species guard their eggs vigorously. For instance, male cichlids and flowerhorn fish often protect the nest. Mouthbrooding—where a parent holds eggs or young in the mouth—is common among cichlids.

Clownfish and groupers can change sex depending on social structure or population needs. This ensures optimal reproductive success.

A few species, such as some killifish, can reproduce without males through parthenogenesis. However, this results in lower genetic diversity.

Females of certain species can store sperm for months or even over a year, delaying fertilization to coincide with favorable conditions.

Most fish breed in spring or summer, when temperature, light, and food conditions are ideal for offspring survival.

Rising water levels or increased current often stimulate spawning, especially in riverine species like sturgeon.

Species like salmon and eels exhibit long-distance migrations from the ocean to freshwater birthplaces to spawn, using remarkable navigation skills.

In aquaculture, hormones are used to stimulate ovulation and sperm release in species like carp.

Fish eggs and sperm are manually collected and combined in controlled environments, widely used for commercial fish production.

To conserve endangered fish species, scientists employ embryo cryopreservation, cloning, and other biotechnologies to safeguard genetic diversity.

Fish reproduction is far from a simple biological act—it’s a suite of intricate behaviors and adaptive strategies shaped by millions of years of evolution.

Understanding these reproductive methods helps in aquaculture, aquarium care, and species conservation. More importantly, it deepens our respect for the complexity of aquatic life and the evolutionary creativity of nature.

animal tags:

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.