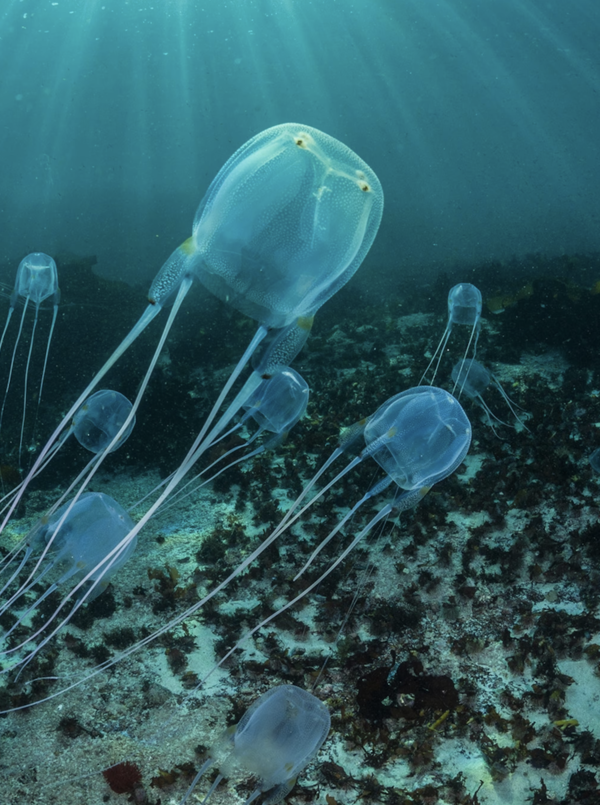

When it comes to the most poisonous animal on the planet, the box jellyfish takes the top spot. Known for its nearly invisible appearance and extremely venomous tentacles, this sea creature has evolved to become one of the most effective hunters in the ocean. Let's dive into what makes the box jellyfish the most dangerous and poisonous animal on Earth.

The Box Jellyfish: Nature's Most Lethal Creature

The box jellyfish, also known as Chironex fleckeri, holds the reputation of being one of the deadliest animals on Earth. Its venom is so powerful that it can kill a human within minutes. This creature, nearly invisible and ghostly in appearance, lives primarily in warm coastal waters of the Indo-Pacific region and has evolved to be an effective hunter with one of the fastest-acting venoms known to science. Here, we’ll look into the box jellyfish’s characteristics, its deadly sting, where it’s found, and how to stay safe around it.

The box jellyfish stands out from other jellyfish in several ways:

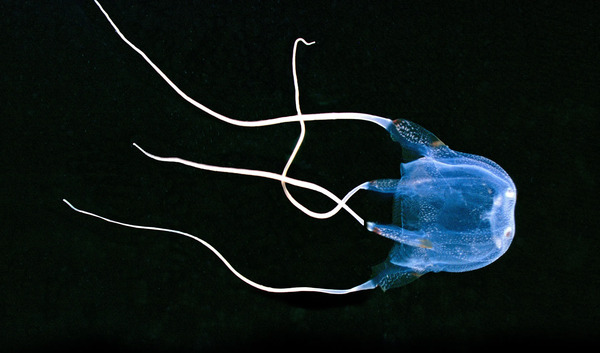

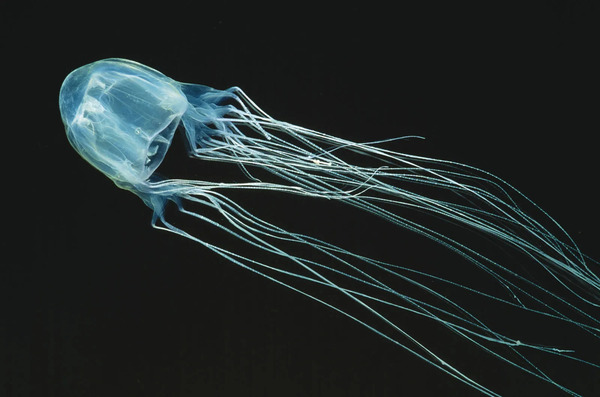

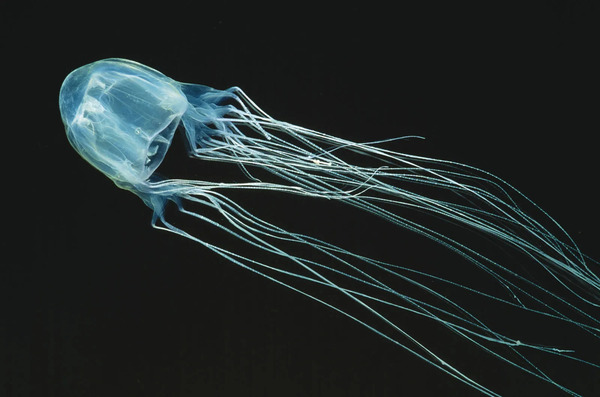

Unique Shape: Unlike typical jellyfish, which are usually round or bell-shaped, the box jellyfish has a cube-like body with four distinct sides. This shape has earned it the “box” in its name.

Tentacles: Each corner of the box jellyfish’s body extends into multiple long, trailing tentacles that can reach up to 10 feet (about three meters). These tentacles are lined with specialized cells called nematocysts, which contain venom sacs.

Fast Swimmer: Unlike other jellyfish, which often drift with currents, the box jellyfish is a surprisingly agile swimmer. It can move quickly, maneuvering through the water to hunt for prey or avoid threats. This active swimming ability allows it to cover more area and is crucial for survival, as it helps avoid beach currents and rocky areas where it could be stranded.

Eyes and Senses: The box jellyfish is unique among jellyfish in that it has a complex sensory system with 24 eyes clustered around its body. Some of these eyes can detect color and are capable of forming images, allowing it to see and actively hunt its prey. This visual ability makes it more of a predator than other jellyfish species, which generally rely on passive drifting.

The box jellyfish’s venom is considered one of the most potent and fast-acting toxins in the animal kingdom. It affects the body in several severe ways:

Neurotoxins and Cardiovascular Impact: The venom contains a combination of neurotoxins, hemotoxins, and cardiotoxins. These components quickly attack the heart, nervous system, and skin cells, causing excruciating pain and, often, death due to heart failure.

Immediate Symptoms: Contact with a box jellyfish’s tentacles can lead to “Irukandji syndrome,” characterized by symptoms like extreme pain, muscle cramps, rapid heart rate, and sweating. In severe cases, it can cause death within minutes if not treated.

Skin Damage: The venomous cells not only cause internal harm but also create deep red welts and burn-like injuries on the skin where the tentacles have made contact. These scars can last for weeks or even become permanent, and in some cases, the affected skin area may begin to necrotize, or die off.

Purpose of Venom: The venom helps the box jellyfish capture small fish and crustaceans, which make up its diet. The venom works almost instantly to paralyze prey, giving the box jellyfish an efficient method for capturing meals in a matter of seconds.

Box jellyfish are primarily found in the Indo-Pacific region, including the northern coasts of Australia, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Their habitat often includes shallow coastal waters, estuaries, and sometimes river mouths.

The “stinger season” is a critical period for beachgoers, generally spanning October to May, when box jellyfish are most active. During these months, local authorities in high-risk regions often post jellyfish warnings and enforce safety measures for swimmers.

Understanding the dangers of box jellyfish and taking proper precautions is essential when swimming in their habitats. Here are some key tips for staying safe:

Pay Attention to Warning Signs: Beaches with known box jellyfish populations will often have warning signs, especially in high-risk regions. Always adhere to these notices and avoid swimming in prohibited areas.

Wear Protective Gear: If swimming in box jellyfish territory, consider wearing stinger suits that cover most of the skin and provide a physical barrier against the jellyfish’s tentacles.

Avoid Touching Jellyfish: Even dead jellyfish can retain venom in their tentacles. Always avoid contact, and do not assume a jellyfish is harmless just because it appears lifeless.

First Aid: If a sting does occur, prompt first aid can save lives. Vinegar is often used to neutralize the nematocysts on the skin, preventing further venom release. Rinse the affected area with vinegar, avoid rubbing the wound, and seek immediate medical attention.

CPR: In severe cases, box jellyfish stings can cause the victim’s heart to stop. Knowing CPR could be lifesaving while waiting for professional help to arrive.

The box jellyfish is both a marvel of evolution and a cautionary reminder of the mysteries of marine life. With a highly complex sensory system, remarkable swimming ability, and potent venom, this creature is a true predator of the ocean. Though small and almost invisible, the box jellyfish’s threat is substantial and should not be underestimated. Observing these jellyfish from a safe distance and respecting their habitat can ensure safety while marveling at one of nature's most lethal creatures.

The box jellyfish demonstrates the beauty and danger of the ocean, reminding us that even the smallest creatures can possess unimaginable power.

The venom of the box jellyfish contains toxins that directly attack the heart, nervous system, and skin cells. Upon contact, the venom can cause:

Intense Pain: The sting from a box jellyfish is notoriously painful, often causing victims to go into shock and lose control of their limbs.

Heart Failure: The venom can trigger an irregular heartbeat, leading to cardiac arrest within minutes if untreated.

Skin Damage: The sting leaves deep red welts that can turn into permanent scars. In severe cases, necrosis, or tissue death, can occur at the sting site.

This combination of symptoms is known as Irukandji syndrome, named after the Irukandji jellyfish, a smaller but equally dangerous relative of the box jellyfish. Many box jellyfish sting victims have described the pain as “unbearable,” comparable to burning or even an electric shock.

The box jellyfish’s powerful venom is an evolutionary adaptation to quickly paralyze and kill its prey. This species feeds on small fish and shrimp, which can quickly escape if not immobilized immediately. The venom acts swiftly to paralyze prey so the jellyfish can consume it without a struggle.

Box jellyfish are found primarily in warm coastal waters across the Indo-Pacific region. They are especially common in the waters off Northern Australia, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. The “stinger season” in these areas typically runs from October to May, when box jellyfish are most active and dangerous to beachgoers.

Staying safe from box jellyfish involves understanding when and where they are most likely to be present. Here are some basic tips:

Observe Warning Signs: Many beaches with known box jellyfish populations post warnings. Always pay attention to signs, especially in Australia and Southeast Asia.

Wear Protective Clothing: If you’re entering box jellyfish habitats, consider wearing a stinger suit, which covers your skin and provides some protection from jellyfish tentacles.

Avoid Touching: If you see a jellyfish, do not touch it. Even dead jellyfish can sting.

Know First Aid: In the event of a sting, vinegar can be used to neutralize some of the venom before medical help arrives. Rinse the sting site with vinegar and avoid rubbing the area, as this can worsen the injury.

While the box jellyfish holds the crown as the most poisonous animal in the world, several other creatures are close contenders:

Poison Dart Frog: These colorful frogs are small but contain a toxin called batrachotoxin that can cause paralysis and death in predators.

Inland Taipan (Snake): Known as the most venomous snake, the inland taipan’s venom is powerful enough to kill multiple humans with one bite.

Stonefish: This fish is highly camouflaged and equipped with venomous spines. It’s considered one of the most dangerous fish in the world.

With its lethal venom and stealthy, transparent body, the box jellyfish is undoubtedly the most poisonous animal in the world. While other creatures have powerful toxins, the box jellyfish’s venom is incredibly potent and can act within minutes, making it both fascinating and terrifying. Remember, if you’re ever in waters where box jellyfish live, take precautions and stay aware of this remarkable yet deadly sea creature.

This beautiful yet perilous animal reminds us that the ocean still holds many mysteries and dangers – and that respecting these creatures is essential for our safety.

The box jellyfish doesn’t have intelligence or an IQ in the conventional sense. IQ, or intelligence quotient, measures cognitive abilities in animals with complex nervous systems, particularly in humans. However, box jellyfish have relatively simple nervous systems and lack a true "brain," meaning they cannot be evaluated for intelligence in the same way as mammals or other animals with advanced cognitive functions.

Nevertheless, box jellyfish exhibit some surprising abilities in terms of sensory perception, movement control, and survival mechanisms. Here’s a detailed look at the unique features that might be considered "intelligent" behaviors in box jellyfish:

Box jellyfish have a highly specialized sensory system, particularly their eyes. Their sensory organs, called "rhopalia," each contain six eyes, giving them a total of 24 eyes distributed across four rhopalia.

High-Resolution Eyes: Some of these eyes (called “lens eyes”) form clear images, similar to the human eye. This allows box jellyfish to recognize and avoid obstacles, a rare trait among jellyfish species.

Visual Processing Abilities: Although they lack a brain, their visual processing system enables them to detect light and shapes, helping them navigate. They can track prey, move toward it, and even avoid obstacles, showing a level of perception that’s unusual among jellyfish.

Unlike other jellyfish that drift passively, box jellyfish can swim with a surprising degree of control. Their boxy, cube-like body and trailing tentacles are structured to allow precise movement.

Active Movement: Box jellyfish are not passive drifters; they control their movements and even actively hunt. While this does not involve “intelligent” decision-making, it demonstrates a high level of motor control through muscle contractions.

Rapid Response: Box jellyfish can quickly change direction and move away from obstacles, demonstrating efficient control over their simple nervous system.

Without a centralized brain, box jellyfish rely on a basic nervous system called a "nerve net." This allows them to coordinate complex behaviors without a central processing unit.

Brainless Control System: Their nerve net encircles their bell, connecting their tentacles and sensory organs, and supports coordinated movement and reaction. Their behavior is automatically managed by this neural network rather than higher-level processing.

Instant Response: This network enables box jellyfish to respond instantly to stimuli, similar to the reflex arcs in other simple animals, where actions are driven by sensory input rather than complex thought.

Box jellyfish have highly developed venom that can instantly immobilize or even kill prey, making their hunting very efficient. This “hunting intelligence” is an evolutionary design that allows them to thrive.

Precise Venom Delivery: Box jellyfish sense prey’s presence, and their stinging cells (nematocysts) in their tentacles react rapidly to release venom. This mechanism illustrates their high adaptability to their environment.

Hunting Efficiency: Without traditional intelligence, box jellyfish still demonstrate highly effective hunting tactics, choosing optimal moments to strike and using venom to swiftly incapacitate prey, displaying a well-refined survival strategy.

While box jellyfish lack a brain, some studies suggest they may have a basic form of learning, particularly in adapting to their environment and modifying behavior accordingly.

Conditioned Reflexes: Studies have shown that box jellyfish may be capable of forming conditioned reflexes, such as avoiding a specific area with obstacles after repeated encounters. However, this learning ability is very limited and does not involve memory or decision-making.

Environmental Adaptation: Box jellyfish can adapt some of their behaviors to environmental changes, such as altering their swimming patterns to avoid strong light or high-temperature areas. This adaptability is due to natural selection rather than intelligence.

Box jellyfish do not possess traditional intelligence or an IQ, as they lack a complex brain structure. However, their sensory system, movement control, hunting mechanisms, and basic adaptability enable them to exhibit certain "intelligent" behaviors. These capabilities are actually highly specialized evolutionary adaptations developed over millions of years to suit their unique survival needs. While they cannot think or learn as higher animals do, box jellyfish’s survival strategies and sensory abilities make them incredibly efficient predators in the marine environment.

Yes, it is possible for humans to survive a box jellyfish sting, but survival often depends on the location and severity of the sting, the speed of medical intervention, and the individual’s physical response. Box jellyfish stings are among the most venomous and dangerous in the world. Without prompt treatment, stings can lead to severe pain, cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, and even death within minutes. However, with immediate first aid and medical attention, many people can recover from a box jellyfish sting. Here’s how survival is possible and what it requires:

Severity of the Sting: Box jellyfish have long, venomous tentacles, and the severity of the sting often depends on the number of tentacles that come into contact with the skin. The more extensive the contact, the greater the venom exposure, and the more likely it is to be life-threatening.

Body Size and Age: Children and individuals with smaller body sizes are generally at greater risk of severe reactions because their bodies absorb the venom more quickly, overwhelming their systems faster than in adults.

Health Condition: Preexisting health conditions, particularly heart or respiratory issues, can complicate recovery, making immediate medical intervention even more critical.

Location of the Sting: Stings closer to the torso, where vital organs are, tend to be more dangerous than those on the limbs. When venom is close to the heart or lungs, it can lead to fatal reactions more quickly.

Box jellyfish venom can cause immediate, intense pain, paralysis, shock, and difficulty breathing. The venom attacks the heart, nervous system, and skin cells, causing symptoms such as:

Excruciating, burning pain at the sting site

Skin welts or severe scarring where tentacles made contact

Muscle cramps and spasms

Dizziness, nausea, or vomiting

Difficulty breathing or chest pain, potentially leading to respiratory failure

Sudden cardiac arrest in severe cases

These symptoms often escalate quickly, which is why rapid response is critical.

Immediate first aid is essential for improving survival chances. Here’s what should be done immediately after a box jellyfish sting:

Remove Victim from Water: Bring the person to shore to prevent drowning if they are struggling due to pain or paralysis.

Rinse with Vinegar: Dousing the sting area with vinegar can help neutralize the venomous cells (nematocysts) and prevent further venom release. Do not use fresh water, as it can trigger additional venom discharge.

Remove Tentacles: Using a tool, such as tweezers or the edge of a card, carefully remove any remaining tentacle fragments without touching them directly to avoid more stings.

CPR if Necessary: If the victim stops breathing or has no pulse, perform CPR while waiting for medical help. Quick intervention can be lifesaving if cardiac arrest occurs.

Seek Medical Attention Immediately: Even after first aid, it’s essential to get professional medical help as soon as possible. Hospitals in high-risk areas often have antivenom and supportive treatments.

In a hospital setting, treatment for a box jellyfish sting may include:

Antivenom: In some cases, box jellyfish antivenom may be administered to counteract the venom’s effects. The antivenom specifically targets the toxins in box jellyfish venom.

Pain Relief and Supportive Care: Morphine or other strong pain relievers can help manage pain, and IV fluids are often given to maintain hydration and support cardiovascular function.

Respiratory and Cardiac Support: Patients may require ventilators or cardiac medications to stabilize breathing and heart function, particularly if they experienced respiratory failure or cardiac arrest.

With rapid first aid and hospital care, many people can survive a box jellyfish sting, though full recovery may take time. Pain may last for days to weeks, and some victims experience lasting skin damage or scars. Severe cases may involve long-term complications, such as nerve damage or heart problems.

In regions where box jellyfish are common, taking preventive measures is essential:

Stinger Suits: Wearing protective suits when swimming can greatly reduce sting risk.

Observe Warning Signs: Beaches in high-risk areas often post jellyfish warnings, especially during peak seasons.

Avoid Night Swimming: Box jellyfish are often more active in low-light conditions.

Surviving a box jellyfish sting is possible, but it requires prompt action, first aid, and medical care. Knowledge of these procedures and awareness of the risks can help swimmers in tropical waters stay safe and improve their chances of recovery if stung.

Box jellyfish are known for their deadly venom, which has sparked extensive research in both toxinology (the study of toxins) and medicine. Scientists have made significant progress in understanding box jellyfish venom’s effects on the human body, and they continue to search for better treatment methods, antivenoms, and even potential medicinal uses. Here’s a look at some key areas of box jellyfish research and its implications in medicine:

Box jellyfish venom is a complex mixture of proteins, peptides, and toxins designed to immobilize prey instantly. This venom acts on the heart, nervous system, and skin cells, causing severe pain, muscle cramps, and sometimes life-threatening conditions like cardiac arrest and respiratory failure. Researchers have isolated several compounds within the venom to understand how it causes such rapid and devastating effects.

Mechanism of Action: Studies reveal that box jellyfish venom affects calcium channels in heart cells, leading to an abnormal heart rhythm or cardiac arrest. This effect explains why some stings can cause death within minutes if the venom quickly reaches the circulatory system.

Pain Pathways: The venom’s mechanism also affects pain receptors, leading to the excruciating pain associated with stings. Research into how the venom interacts with these receptors is critical to developing more effective pain relief for sting victims.

Cellular Damage: Researchers are studying how the venom damages skin cells and leads to necrosis (tissue death), which causes the characteristic scarring in survivors of box jellyfish stings. Insights from this research help in finding ways to mitigate long-term damage.

Antivenom has long been a primary treatment for box jellyfish stings, particularly in Australia, where the most venomous species, Chironex fleckeri, is common. Here’s how antivenom works and how research is advancing in this area:

Traditional Antivenom: The standard box jellyfish antivenom is produced by injecting small amounts of venom into animals (typically horses) to create an immune response, after which antibodies are harvested and refined. When administered to a sting victim, these antibodies neutralize the venom, preventing it from causing further harm.

Efficacy and Limitations: While antivenom is life-saving, it is not always immediately effective in severe cases where venom has rapidly spread through the body. Researchers are now focusing on improving antivenom's effectiveness, stability, and availability in regions with high sting incidences.

Synthetic and Peptide-Based Antivenoms: Scientists are developing synthetic antivenoms that could potentially be more effective and less costly to produce. These antivenoms would mimic the action of natural antibodies, neutralizing the venom’s toxins more quickly and thoroughly.

Application Techniques: Advances in delivery methods, such as injectors for rapid, localized delivery to the sting site, are also in development. These may improve the speed of treatment in critical moments following a sting.

Managing pain from a box jellyfish sting is challenging, as the venom causes severe, often long-lasting pain. Researchers are exploring novel approaches to alleviate pain and minimize tissue damage:

Vinegar Rinse: Applying vinegar immediately after a sting has been shown to neutralize undischarged nematocysts (venomous cells) on the skin, which can help prevent additional venom from being released. Researchers continue to examine how vinegar affects different box jellyfish species’ venom and if other rinses may be more effective.

Pain Medications: Morphine and other opioids are often used to manage box jellyfish sting pain in hospitals, but these can have side effects. Researchers are studying more targeted pain-relief compounds that work on the specific pain pathways affected by the venom.

Local Anesthetics and Cooling: Applying cold packs or topical anesthetics to the sting area can reduce inflammation and numb pain, and research is ongoing into the most effective ways to reduce pain without causing further damage to the skin.

Interestingly, some scientists are studying the venom’s potential applications in medical research. Despite its dangers, box jellyfish venom could hold therapeutic properties for specific medical conditions. Key areas of exploration include:

Cardiovascular Research: Since the venom affects heart cells, it may provide insights into heart function and arrhythmias. By understanding how the venom disrupts heart rhythms, scientists hope to develop new treatments for heart-related conditions.

Pain Management Research: The venom’s unique way of interacting with pain receptors might contribute to new pain management drugs. Researchers are exploring how certain proteins in the venom could be altered to produce pain-relieving medications without harmful effects.

Neurological Insights: Box jellyfish venom’s impact on the nervous system is also a focus area. By studying how venom interferes with nerve function, scientists may uncover new treatments for nerve-related conditions or ways to protect nerve cells from damage.

Despite the progress, there remain significant challenges in box jellyfish research and medicine:

Venom Complexity: Box jellyfish venom is complex and varies by species, which complicates efforts to develop a universal treatment or antivenom. Researchers continue to study different box jellyfish species to better understand the variations in their venom.

Accessibility of Treatment: In areas where box jellyfish are common, quick access to antivenom and effective treatments is often limited. Efforts are ongoing to make life-saving treatments more available and affordable in coastal communities where stings are frequent.

Education and Prevention: Beyond treatment, educating the public on how to avoid box jellyfish and what to do if stung remains a priority. Increased awareness and safety measures can reduce the need for emergency treatments.

Box jellyfish research is advancing our understanding of this dangerous creature and improving treatment options for sting victims. From enhancing antivenom efficacy to investigating venom’s medical potential, scientists continue to make strides in mitigating the risks associated with box jellyfish and even finding benefits within their venom. The ultimate goal of this research is to save lives and possibly unlock new, life-improving medical treatments.

animal tags: Box-jellyfish

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.