When thinking about venomous animals, mammals are rarely the first to come to mind. Yet, a few extraordinary mammals use venom for hunting, defense, or survival. While rare, these venomous species showcase the diversity and adaptability of life on Earth. Let’s explore the top 10 venomous mammals, ranked by their unique venom delivery systems and impact on prey or predators.

Venom Delivery: Spurs on hind legs (males only)

Venom Effects: Intense pain, swelling, and nausea

Habitat: Australia

The platypus is the poster child for venomous mammals. Males have sharp spurs on their hind legs that deliver venom capable of causing excruciating pain and prolonged swelling. While not life-threatening to humans, the venom is potent enough to incapacitate predators or rivals during mating season. This feature makes the platypus the most venomous mammal known.

Venom Delivery: Glands near elbows, combined with saliva

Venom Effects: Allergic reactions, anaphylactic shock

Habitat: Southeast Asia

The slow loris is the only venomous primate. It secretes a toxic substance from glands near its elbows, which it mixes with its saliva before biting. This venom is a defense mechanism against predators and can cause severe allergic reactions in humans, even leading to anaphylaxis. Despite its cuddly appearance, the slow loris is a formidable defender when threatened.

Venom Delivery: Grooved lower teeth

Venom Effects: Paralyzes small prey

Habitat: Hispaniola (Dominican Republic and Haiti)

The solenodon, a nocturnal insectivore, is among the few mammals that deliver venom through their bite. Its venom paralyzes or kills prey like insects and small reptiles, making it easier to feed. Though not dangerous to humans, a bite may cause localized swelling or discomfort.

Venom Delivery: Salivary glands

Venom Effects: Paralysis of prey, mild irritation in humans

Habitat: North America

This tiny mammal has venomous saliva that paralyzes insects and small animals, which the shrew uses to store fresh prey for later consumption. Though their venom isn’t harmful to humans, bites can cause mild swelling and redness. Their venom is highly effective in helping them survive as fierce predators despite their small size.

Venom Delivery: Salivary venom

Venom Effects: Paralyzes earthworms and insects

Habitat: Europe

The European mole uses venomous saliva to immobilize prey, particularly earthworms, which it stores in underground chambers. Though harmless to humans, their venom ensures that their food supply stays fresh. These small mammals demonstrate how venom can be a useful adaptation for survival underground.

Venom Delivery: Saliva with anticoagulants

Venom Effects: Prevents blood clotting, minor irritation

Habitat: Central and South America

Vampire bats may not have the most toxic venom, but their saliva contains anticoagulants that prevent blood from clotting. This allows them to feed on their host’s blood without interruption. While their bite is not harmful to humans, their venom plays a critical role in their survival strategy.

Venom Delivery: Venomous saliva

Venom Effects: Paralysis and immobilization of prey

Habitat: Europe and parts of Asia

The European water shrew is a rare venomous mammal that produces venom in its salivary glands. This venom is used to immobilize prey such as insects, fish, and amphibians. While their venom isn’t dangerous to humans, a bite can cause mild irritation. Its venomous bite is a key adaptation for hunting larger prey relative to its size.

Venom Delivery: Fur soaked in plant toxins

Venom Effects: Can cause sickness or deter predators

Habitat: East Africa

The crested rat doesn’t produce venom internally but earns its place on this list by using toxins from the Acokanthera plant, which it applies to its fur. Predators that come into contact with this toxic fur may suffer severe sickness, discouraging further attacks. This clever use of external toxins highlights nature’s creativity in defense mechanisms.

Venom Delivery: Spurs on hind legs (males only)

Venom Effects: Inconclusive (not toxic to humans)

Habitat: Australia and New Guinea

Male echidnas, like platypuses, have spurs on their hind legs. While the venom they produce is not dangerous to humans, its function remains poorly understood. Scientists believe it may play a role in mating behavior, making this monotreme an intriguing example of venom evolution.

Venom Delivery: Grooved teeth with salivary venom

Venom Effects: Paralyzes prey

Habitat: Hispaniola

Another solenodon makes this list for its remarkable venomous bite. This ancient insectivore species uses venom to incapacitate insects and small reptiles. Its venom is harmless to humans but vital for its predatory lifestyle.

Venomous mammals are a fascinating rarity, with each species showcasing how nature has adapted toxins for hunting, defense, or survival. From the infamous platypus to the venomous water shrew, these creatures highlight the diversity and ingenuity of life on Earth. Understanding these mammals helps us appreciate their role in the ecosystem and the unique evolutionary paths they represent.

When we think of mammals, the idea of venom or chemical defenses usually doesn’t come to mind. Unlike reptiles, insects, or marine creatures, venomous mammals are rare. However, some mammals utilize venom from external sources or emit noxious chemicals to protect themselves. These adaptations are remarkable examples of evolution’s creativity, showcasing how even non-venomous animals can effectively deter predators. Below, we explore five fascinating mammals that use venom or chemicals as defense mechanisms.

Hedgehogs may look like adorable creatures, but don’t be fooled—these tiny mammals can be formidable when threatened. While hedgehogs don’t produce venom themselves, they ingeniously incorporate toxins from other animals into their defense strategies.

In the wild, hedgehogs are known to hunt poisonous toads, biting into their poison glands or chewing their skin. This process allows them to extract and apply the toad’s poison onto their spikes. The hedgehog spreads the toxins by licking its spines, effectively turning its quills into venomous weapons.

When a predator approaches, the hedgehog curls into a ball, exposing its poison-coated spikes to ward off the threat. This clever adaptation highlights the resourcefulness of these small creatures. While they don’t generate venom naturally, their ability to use external toxins makes them a surprising contender in the animal kingdom’s arsenal of defenses.

Skunks are infamous for their pungent spray, a powerful defense mechanism that keeps most predators at bay. While their spray isn’t venomous, it is highly irritating and can cause significant discomfort to humans and animals alike.

The skunk’s spray originates from its anal glands and contains a chemical compound called N-butylmercaptan, a sulfur-based substance with a foul odor. When sprayed, this oily substance clings to skin and fur, causing stinging, burning sensations in the eyes, tearing, and sometimes short-term respiratory irritation.

For dogs, exposure to skunk spray can lead to drooling, vomiting, swollen eyes, sneezing, and even temporary blindness. In rare cases, prolonged exposure may damage red blood cells. Skunks often use this chemical weapon as a last resort, relying on their black-and-white warning coloration to deter potential threats before deploying their infamous spray.

Closely resembling skunks in both appearance and behavior, the striped polecat is another mammal that employs a chemical defense. Native to Africa, this creature releases a noxious spray from its anal stink glands to deter predators.

The striped polecat’s spray has effects similar to those of skunk spray, including temporary blindness, irritation of mucous membranes, and a strong burning sensation. This foul-smelling liquid is potent enough to give most predators second thoughts about attacking. While not technically venomous, the polecat’s chemical arsenal ensures it remains well-protected in the wild.

The pangolin, often referred to as the "scaly anteater," is famous for its unique keratin scales that form a tough, armor-like shield. When threatened, pangolins roll into a tight ball, leaving predators with little to attack.

But pangolins don’t stop at physical defense. These mammals can also release a noxious chemical from glands near their anus, much like a skunk. Although they don’t spray the substance, the pungent odor is enough to repel most predators. This dual-layered defense system—armor and odor—makes the pangolin one of nature’s most fascinatingly adapted mammals.

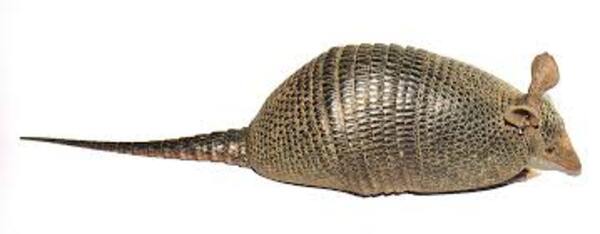

The greater long-nosed armadillo, a South American species, is another mammal equipped with an armored shell of keratin scales. While its tough exterior provides excellent protection against physical attacks, this armadillo has an additional defense mechanism: musk.

When threatened, the greater long-nosed armadillo emits an unpleasant musky odor from its scent glands. Though the smell is not venomous, it is strong enough to deter potential predators. Combined with its protective shell, this chemical defense ensures that the armadillo can fend off threats effectively.

The mammals discussed here demonstrate the incredible diversity of evolutionary adaptations. Some, like the hedgehog, creatively repurpose venom from other animals, while others, such as the skunk, rely on chemical irritants to keep predators at bay.

While venom and toxins are rare among mammals, the ability to emit or utilize chemical defenses highlights their resourcefulness in survival. These unique adaptations not only protect these animals from harm but also showcase the innovative ways mammals have evolved to thrive in their environments.

From hedgehogs with poison-coated quills to skunks with their infamous spray, these mammals exemplify how nature equips creatures to survive in a competitive world. Their defenses may not always be venomous in the traditional sense, but they are undoubtedly effective. As we continue to study the natural world, these animals remind us of the incredible ingenuity of evolution.

animal tags: Hispaniolan-Solenodon

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.