Associate researcher Wang Yuan of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, collaborated with the research team of Zhang Hanwen, a doctoral student at the University of Bristol, UK, and Professor Mark Purnell of the University of Leicester, UK, using the 3D micro-mark texture analysis technology of teeth developed in recent years ( dental microwear texture analysis (DMTA), conducted a comprehensive analysis and preliminary discussion on the feeding habits of fossil proboscideans from different periods of the Pleistocene in South China. The research results, with Associate Researcher Wang Yuan as the corresponding author, were recently published online in the international SCI journal "International Quaternary International.

Elephant fossils have become important indicator fossils for the reconstruction of the late Cenozoic terrestrial paleoecological environment due to their fast evolution rate, wide spatial and temporal distribution, and rich environmental indicators. Since 2004, a scientific research team led by researcher Jin Changzhu of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, has successively discovered mammals representing different periods of the Pleistocene with good inheritance and continuity in the Quaternary caves and fissure accumulations in Chongzuo, Guangxi and surrounding areas. There are more than ten groups. Systematic research on the elephant fossils in the above-mentioned mammal groups shows that the evolution and replacement of proboscideans in the Quaternary of southern my country are regular: the early Pleistocene is characterized by the combination of Chinese mastodon and South China Stegodon; the early Pleistocene The Chinese Mastodon and the South China Stegodon may have become extinct in South China at the end of the century and were replaced by the Eastern Stegodon; the Asian Elephantus began to flourish in the late middle Pleistocene and played a leading role in the fauna together with the Eastern Stegodon. The above-mentioned evolution and replacement of proboscideans promoted the further division of the Quaternary biostratigraphic sequence in South China: the early Pleistocene Gigantopithecus-Sinomastodon fauna, the Middle Pleistocene giant panda-stegodon fauna (narrow sense) and Late Pleistocene Asian elephant fauna.

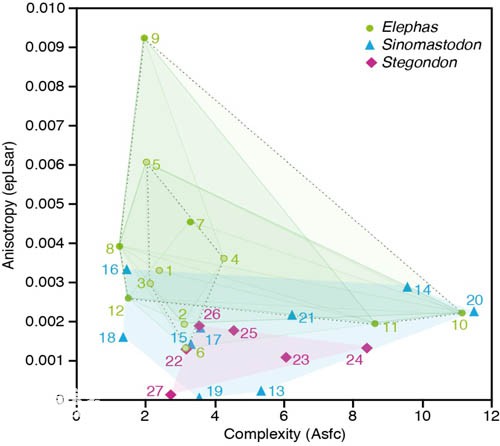

Using DMTA research methods to explore the dietary habits of ancient mammals and ancient humans has become a popular direction in paleontological research in recent years. Compared with the traditional method of studying micro-marks on animal tooth fossils using ordinary optical microscopes or scanning electron microscopes, DMTA has more significant advantages in the rigor and repeatability of the data collection process. By comparing the complexity and anisotropy of molar micromarks in Chinese mastodon, Stegodon and Asian Elephants-Are-Endangered.html">elephants, the researchers found that the Chinese Mastodon in the Early Pleistocene in South China was different from the Stegodon across the entire Pleistocene. It mainly likes to eat young leaves, which is a statistically significant difference from the Asian elephant which has a wider food habit and eats both grass and leaves.

Chinese Mastodon and Stegodon coexisted in East Asia during the Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. However, in the long process of evolution, the Chinese mastodon retained its original hump-shaped molars, while the saber-toothed elephant evolved ridge-shaped teeth that could chew plants more efficiently. In the late Early Pleistocene about 1 million years ago, an important biological event occurred in the Chongzuo area, mainly manifested in the disappearance of tropical forests and the extinction of Tertiary relict mammals (including the Chinese mastodon). In the context of the above-mentioned environmental changes, the saber-toothed elephant, which was also a tendervore (browser), squeezed out the Chinese mastodon in the competition for survival due to its teeth that were more suitable for chewing plants, causing the latter to become extinct in China. On the contrary, the differences in feeding habits of saber-toothed Elephants-Are-Endangered.html">elephants and Asian Elephants-Are-Endangered.html">elephants created an ecological resource distribution situation that allowed the two to coexist from the late mid-Pleistocene to the end of the Pleistocene. The saber-toothed elephant became extinct along with a large number of large mammal species around the world at the end of the Pleistocene, but the Asian elephant is still active in Xishuangbanna and other areas of Yunnan, my country to this day.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Open Project of the State Key Laboratory of Modern Paleontology and Stratigraphy, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the British Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) project.

Figure 1 Ecological restoration map of late Pleistocene elephants in South China. The Asian elephant (left) has a larger proportion of herbivorous diet, while the saber-toothed elephant (right) mainly eats young leaves (drawn by Nicola Heath)

Figure 2 Complexity and anisotropic distribution of molar enamel micromarks in Quaternary proboscis from South China (provided by Wang Yuan and Zhang Hanwen)

animal tags: Elephants Proboscidea

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.