Key takeaways

• “Ugly” is a human label; most of these looks are hard-won adaptations that help the animals eat, move, signal, or survive.

• From the California condor’s bald head to the star-nosed mole’s sensory “star,” each trait does a job.

• Several species here are threatened or endangered; understanding their biology is a step toward protecting them.

North America’s largest soaring land bird pairs a bald, wrinkled head with a 9-foot (2.7 m) wingspan built for riding thermals. The naked head is hygienic for a scavenger that feeds on large carcasses. After a 1980s crash from lead poisoning, intensive breeding and releases lifted the wild population into the hundreds. “Homely” up close, majestic on the wing.

This hairless, wrinkled rodent lives like a termite in underground colonies with a queen and non-breeding workers. Its buck teeth dig without letting soil into the mouth; skin and nerves make it unusually pain-tolerant and low-oxygen ready. Not pretty—yet it’s a goldmine for research on aging, cancer resistance, and hypoxia.

At abyssal depths, the blobfish’s gelatinous body matches surrounding pressure and looks like…a normal fish. Only when hauled to the surface does it deform into a droopy blob—an artifact of pressure change, not its natural form. A reminder that “ugly” can be context.

Madagascar’s nocturnal primate sports orange eyes, rodent-like teeth, and a skeletal middle finger used to drum wood and fish grubs out of tunnels—think woodpecker, but with hands. Superstitions once spurred persecution; today habitat loss is the main threat. Eerie looks, ingenious foraging.

Males carry a pendulous nose that works like a built-in resonator—bigger noses, louder calls, stronger mate appeal. These Borneo specialists are also powerful swimmers. Comical features? Maybe. But they’re fine-tuned for communication in dense forests.

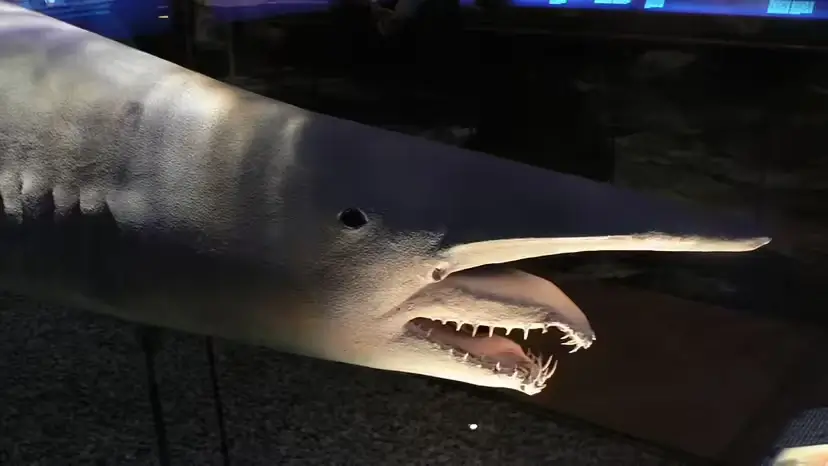

A living fossil with a blade-like snout and slingshot jaws that shoot forward to snag prey. Rosy skin and protruding teeth look monstrous, yet its lifestyle is slow-motion and deep-sea. Form follows function in the dark.

Warty skin, tiny eyes, and a massive body make the world’s largest amphibian look prehistoric. Those folds absorb oxygen in cold, fast streams. Overharvest and habitat loss have driven it to the brink, but its “odd” anatomy is a breathing system built for mountain waters.

Males develop a helmet-like head with expanded lips, nasal chambers, and larynx—hardware for deafening courtship calls in nocturnal leks. Females look fox-faced and far daintier. Strange visage, spectacular acoustics.

The facial “flower” is a 22-tentacle Eimer’s organ packed with ~25,000 touch receptors. It maps prey in mud at extreme speed—this mole is the fastest known eater among mammals. Odd nose, unmatched tactile radar.

The male’s inflatable proboscis isn’t for show—it amplifies roars to defend harems across windy beaches. Behind the blubbery profile is a champion diver, routinely reaching 1,000+ m in search of squid and fish. Big nose, big lungs, big ocean.

Bottom line: what our eyes call “ugly” is often elegant engineering—solutions to cold, darkness, decay, low oxygen, or the need to be heard. If these animals make you look twice, let that curiosity fuel respect and conservation, not judgment.

animal tags: ugly animals

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.