Ducks are one of the most well-known waterfowl species and are often associated with their ability to waddle and swim gracefully on water. However, many people wonder: "Can ducks fly?" The answer is a resounding yes—most species of ducks are strong fliers, capable of covering impressive distances. This article will explore the various factors that influence a duck's ability to fly, the species that are exceptional flyers, and how their physical characteristics aid in flight.

The simple answer is that most ducks can fly, but there are a few exceptions.

Most species of ducks are excellent fliers and often migrate over vast distances to find warmer habitats or suitable breeding grounds.

Some domestic duck breeds and species have lost the ability to fly due to selective breeding or adaptation to specific environments.

Domestic Ducks: Breeds such as Pekin and Indian Runner ducks have been bred for their meat, eggs, or ornamental purposes and often lack the muscle strength for flight.

Flightless Wild Ducks: Certain wild species, like the Steamer Duck, have evolved to be non-flying due to the absence of predators in their native habitats.

Ducks have unique adaptations that make them strong fliers.

Ducks possess pointed wings with strong flight feathers that allow for rapid and powerful wingbeats.

Aspect Ratio: Ducks have a high wing aspect ratio, meaning their wings are relatively long compared to their width, making them suited for sustained flight.

Feather Molting: Ducks molt their flight feathers once a year, temporarily rendering them flightless for a few weeks.

Flight Muscles: Ducks have robust pectoral muscles, which make up about 20-25% of their body weight, providing the power needed for flight.

Leg Placement: Ducks’ legs are positioned farther back on their bodies, which aids swimming but makes takeoff from the ground or water more challenging.

Ducks have a distinctive way of taking off and landing:

Takeoff: Ducks must beat their wings quickly and often require a running start, especially from the water.

Landing: Ducks are adept at gliding onto the water’s surface, using their wings to slow down and their webbed feet to create friction upon contact.

Ducks are known for their long-distance migrations, often covering thousands of miles.

Seasonal Changes: Ducks migrate to escape cold temperatures and find food and suitable breeding grounds.

Reproductive Cycle: Migration helps ducks reach areas where they can nest and rear their young in safety.

Some species, such as the Northern Pintail and Mallard, can fly over 1,000 miles without stopping.

Certain migratory routes, known as flyways, span continents and involve rest stops where ducks can refuel.

Flying Speed: Ducks typically fly at speeds of 40-60 miles per hour (65-95 km/h), but with tailwinds, some can reach speeds up to 70 mph.

Altitude: Ducks usually fly at altitudes between 200 and 4,000 feet but have been recorded flying as high as 20,000 feet during migration.

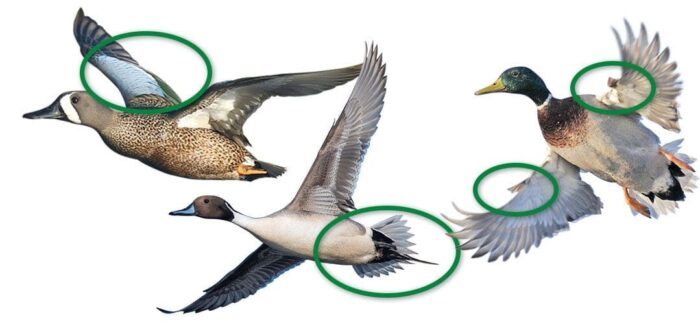

One of the most widespread and adaptable species.

Known for its ability to migrate across continents.

Recognized for its long neck and streamlined body.

Capable of sustained high-speed flight during migration.

Teals are small but incredibly fast fliers.

The Green-winged Teal can reach remarkable speeds during migration.

Found primarily in North America.

Known for its short-distance flights and agility, often flying between forested wetlands.

Sea ducks known for their resilience and capability to endure cold Arctic winds during flight.

Some species and breeds of ducks are unable to fly due to specific evolutionary adaptations or breeding.

Native to South America, most Steamer Duck species are flightless.

They use their strong wings to “steam” across the water rather than fly.

Pekin Ducks: Selectively bred for size and weight, making them too heavy to sustain flight.

Indian Runner Ducks: Bred for their upright posture and egg-laying ability, they lack the wing strength for flight.

Tailwinds: Strong tailwinds can significantly increase flight speed and distance.

Headwinds: Headwinds slow ducks down and increase energy expenditure.

Ducks need suitable wetlands and lakes as rest stops during long migrations. Habitat loss can disrupt their flight patterns.

During molting, ducks shed their flight feathers and temporarily lose their ability to fly. This makes them vulnerable to predators and reliant on secluded habitats.

A duck’s body is designed for efficient flight, with a rounded torso and long wings.

Ducks have an advanced respiratory system with air sacs that allow continuous oxygen flow during flight, enabling them to sustain long journeys.

Ducks build fat reserves before migration to fuel their energy-intensive flights.

The image of ducks flying south in the fall is a common symbol of change and the passage of time.

Flying ducks contribute to the dispersal of plant seeds and aquatic life across regions, helping maintain biodiversity.

Most species of ducks can fly, but some domestic and wild species, such as the Steamer Duck, cannot.

Ducks typically fly at speeds of 40-60 mph but can reach speeds of 70 mph with favorable winds.

Yes, many migratory ducks fly at night to avoid predators and take advantage of calmer air currents.

Ducks build up fat reserves, rest at staging areas, and form flocks to conserve energy during long flights.

Selective breeding for traits such as larger body size or egg production has resulted in some domestic breeds losing the ability to fly.

Ducks are remarkable fliers, capable of traversing vast distances and enduring harsh conditions. Their ability to fly is influenced by their species, environment, and evolutionary traits. While some ducks have adapted to a flightless lifestyle, the majority of wild ducks rely on their strong wings for survival, migration, and daily activities. Understanding the flight capabilities of ducks not only deepens our appreciation for these versatile waterfowl but also highlights their vital role in maintaining ecological balance.

animal tags: ducks

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.