Ambergris is a rare, waxy substance that forms inside the intestines of sperm whales. For centuries it was called whale “vomit,” but modern research points to a digestive by-product—closer to a biliary or fecal concretion—that helps protect the whale’s gut from hard, indigestible squid beaks. Most of it likely passes out with feces; very occasionally it floats free in the open ocean.

Fresh ambergris is soft, dark, and pungent—think barnyard or dried dung. Time and sunlight transform it at sea: over years to a decade it hardens, lightens to grey, blond, or nearly white, and the odor mellowes into something sweet, musky, tobacco-leathery, and salty. That metamorphosis is what perfumers pay for. Within aged ambergris is ambrein, an odorless alcohol that oxidizes into fragrant molecules and acts as a powerful fixative—it makes delicate top notes last on skin and “rounds” a perfume’s whole composition.

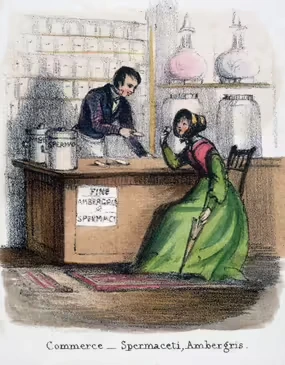

Rarity is the first driver. Only sperm whales produce it; only a tiny fraction of individuals do; and most ambergris never reaches shore. When a well-aged, pale piece does wash up, it can fetch high prices on specialty markets. The second driver is function: fine, naturally aged ambergris is still considered a gold-standard fixative in high perfumery, even though excellent synthetic substitutes—such as Ambroxide/Ambroxan, Cetalox, and related ambrein derivatives—now shoulder most of the work.

The controversy is legal and ethical. In the United States, ambergris is treated as a product of a protected marine mammal and is illegal to buy or sell under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (and typically the Endangered Species Act). Other countries regulate it differently—some allow trade in naturally beached ambergris, others restrict or ban it. Always check local law before touching or marketing a find, because rules vary and enforcement can be strict.

A sperm whale’s squid-heavy diet supplies lots of indigestible beaks and pens. The current hypothesis: the whale secretes material that binds and smooths these sharp fragments, forming a waxy mass in the intestines. Most passes in small pieces and sinks; very rarely, a larger mass is expelled and floats, beginning its long, oxidative aging at sea.

Genuine beached ambergris tends to be light for its size, with a waxy, slightly greasy feel and a rounded, weathered exterior. Colors shift from black or charcoal (fresh) to grey, marble-mottled, blond, or chalky white (older). When warmed between fingers, aged pieces release a complex, pleasant, marine-musky scent rather than a harsh manure reek. Many specimens show embedded fragments or a crumbly, crystalline interior when cut—though cutting is discouraged.

Common look-alikes include candle or boat wax, palm wax, congealed cooking oil, fat and tallow, pine resin, asphalt, hardened plastic, and even weathered pumice. “Hot-needle” and flame tests are unreliable and risky. The only trustworthy route is laboratory analysis and examination by an experienced ambergris assessor; chemists often look for ambrein/cholesterol profiles and related markers.

Handle it minimally and don’t break or melt it. Take clear photos, note the location and date, and contact appropriate wildlife or marine authorities first—especially in countries where possession or trade is restricted. If local law allows you to retain a sample, a specialized lab or a reputable perfume materials broker can advise on analytical testing. Be cautious of unsolicited buyers and inflated valuations; quality, aging, and legality determine price more than weight alone.

Market anecdotes swing wildly with color, age, aroma quality, cleanliness, and legality. Pale, well-aged “white” or “blond” ambergris commands the highest premiums; fresh black material is far less valuable. Because supply is unpredictable and laws are complex, most brands now rely on bio-identical synthetics that offer a consistent, cruelty-free, and legal path to the same diffusive, skin-tenacious glow ambergris is famous for.

Responsible use starts with not harming whales. Natural, beach-cast ambergris is a post-whale product; no reputable buyer should seek material from killed or disturbed animals. Where trade is illegal, the ethical choice and the legal one align: don’t traffic. Where it’s permitted, traceability and non-interference are the minimum standard—and many perfumers prefer synthetics to avoid any conservation gray areas.

Is it vomit or poop? Likely a fecal/gallstone-like concretion, not true vomit.

Why does aged ambergris smell good? Oxidation and photochemistry turn ambrein into a smooth, diffusive, musky-ambery scent and provide exceptional fixative power.

Can I sell what I find? Depends on your country. It’s illegal in the U.S.; elsewhere it may be regulated or permitted. Verify before you act.

Do perfumes still use real ambergris? A few luxury houses do, usually in niche releases where legal; most rely on Ambroxide/Cetalox-type molecules that capture the effect without the legal and ethical baggage.

animal tags: ambergris

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.