Among all the creatures that have ever lived in Earth’s oceans, few inspire as much awe and fear as the Megalodon shark (Carcharodon megalodon). This prehistoric predator, famous for its massive teeth and formidable size, dominated the seas for millions of years. Fossil evidence suggests that megalodons thrived between 19.8 million and 2.6 million years ago, before their population suddenly declined and eventually disappeared.

In this article, we’ll explore what scientists know about the megalodon, review leading theories about its extinction, and address whether there’s any chance this giant predator still exists today.

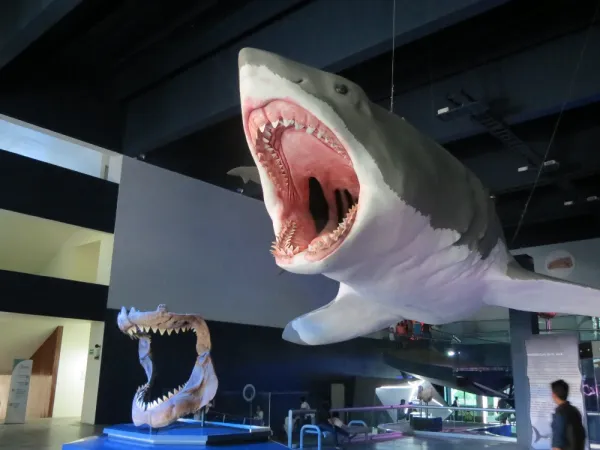

The megalodon was a species of giant shark that lived during the Cenozoic Era—from the early Miocene through the late Pliocene. Its name comes from the Greek words megas (large) and odon (tooth). A single megalodon tooth could measure more than 15 centimeters (6 inches) long.

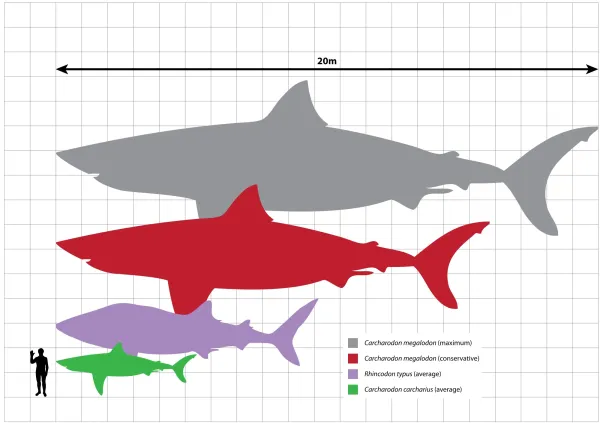

Based on fossilized teeth and vertebrae, scientists estimate that adult megalodons could reach up to 18 meters (60 feet) in length, making them the largest shark species ever known. For comparison, today’s great white sharks typically measure only 6–8 meters (20–26 feet).

Megalodons were apex predators, feeding on a variety of prey, including large whales, seals, dolphins, and other marine life. They preferred warm tropical waters and often used shallow coastal zones as nursery grounds. For more than 17 million years, they reigned as the ocean’s top predator—until conditions shifted dramatically in the late Pliocene.

There is no single definitive answer as to why the megalodon went extinct. Instead, scientists believe a combination of environmental and ecological factors contributed to its decline.

Around 3 million years ago, the North and South American continents connected, forming the Isthmus of Panama. This reshaped global ocean currents and triggered a period of global cooling and ice ages.

Oceans became significantly colder.

Warm, shallow waters—the megalodon’s breeding grounds—shrank dramatically.

Colder waters also reduced populations of marine mammals, including whales that made up much of the megalodon’s diet. With less food available, survival became harder.

Fossil evidence even suggests possible cannibalism among megalodons, as adults may have preyed on juveniles during times of scarcity.

At the same time, new predators emerged, including early orcas and toothed whales. While these species could be prey for megalodons, they also competed for the same food resources. Unlike the megalodon, these smaller, more adaptable hunters may have thrived in the changing environment.

Taken together, these three factors—climate change, lack of prey, and increased competition—likely sealed the fate of this prehistoric giant.

Legends and myths suggest that megalodons may still roam the deep sea, occasionally mistaken for large great white sharks. However, the scientific consensus is clear:

There is a 99.9% probability that the megalodon is extinct.

No credible fossil, sighting, or evidence has ever confirmed its survival.

Modern great white sharks are considered the evolutionary descendants of megalodons, adapted to cooler oceans and smaller prey.

The megalodon was one of Earth’s most powerful marine predators, dominating the oceans for millions of years. But as the planet’s climate cooled, food became scarce, and competition increased, the once-unmatched giant could not survive.

Although it disappeared more than 2.5 million years ago, the megalodon continues to capture human imagination. Its enormous fossilized teeth and jaw reconstructions remind us of the breathtaking scale of prehistoric life and the fragile balance of ecosystems—even for the mightiest of predators.

animal tags: megalodon shark

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.