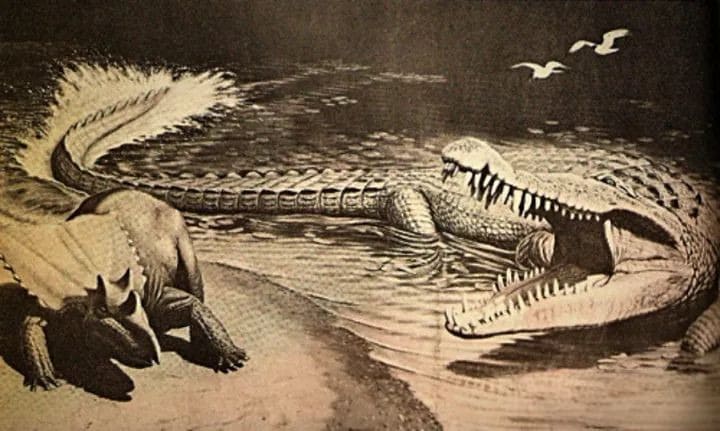

Deinosuchus (“terrible crocodile”) was a colossal crocodylian within the Alligatoroidea superfamily that prowled eastern North America during the Late Cretaceous (about 80–73 million years ago). It ranks among the largest crocodyliforms ever discovered and likely preyed on large dinosaurs along shorelines and river margins.

Name origin: from Greek deinos (terrible) + souchos (crocodile).

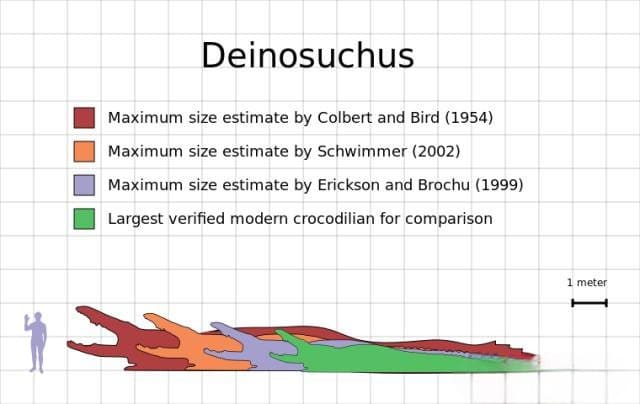

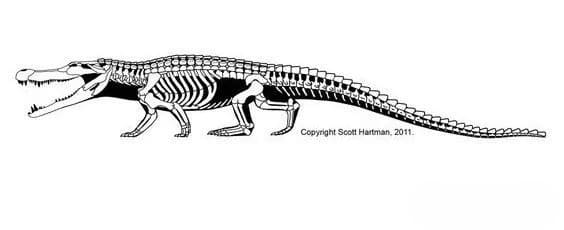

Because most finds are skull fragments and scattered bones, total length must be inferred, and estimates vary widely.

1954 – Colbert & Bird:

Lower jaw ~ 2 m; by comparison with other giants, proposed a ~15 m maximum length (extreme upper bound).

1999 – Erickson & Brochu:

More conservative ~8–10 m total length.

2002 – Schwimmer:

Suggested smaller eastern populations around ~8 m / ~2.3 t, and larger western populations up to ~12 m / ≥8.5 t.

Consensus: regardless of method, Deinosuchus exceeded any living crocodylian in mass; even the smallest credible estimates put it well above modern size ceilings.

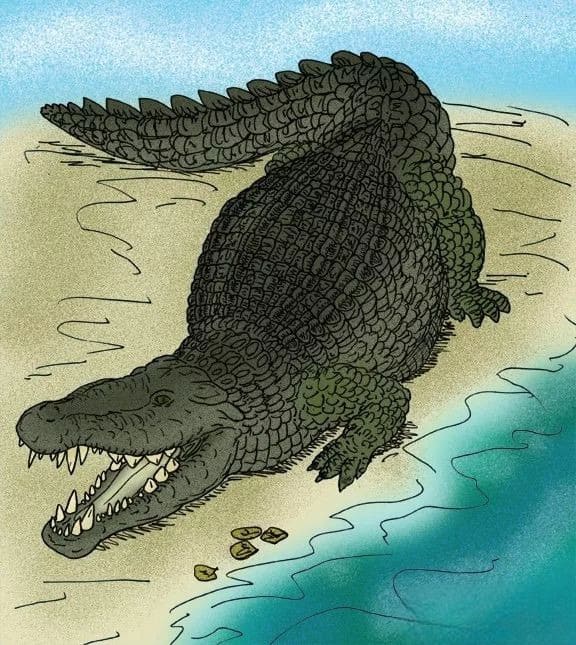

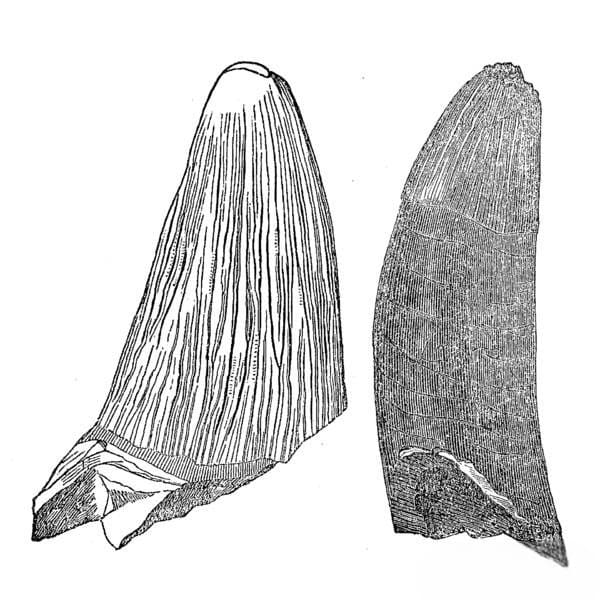

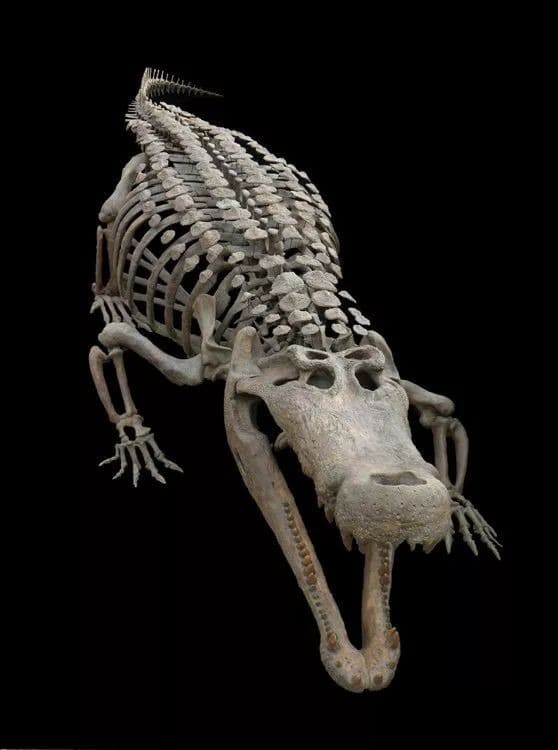

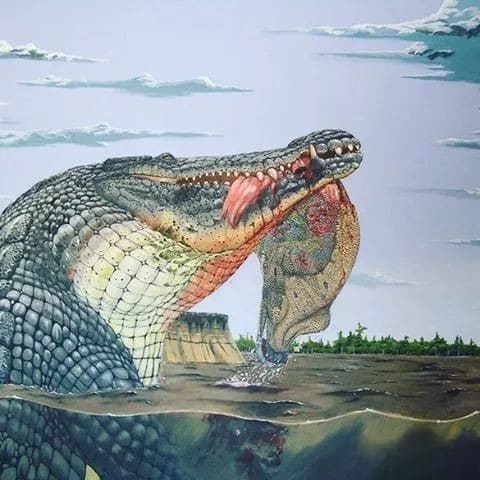

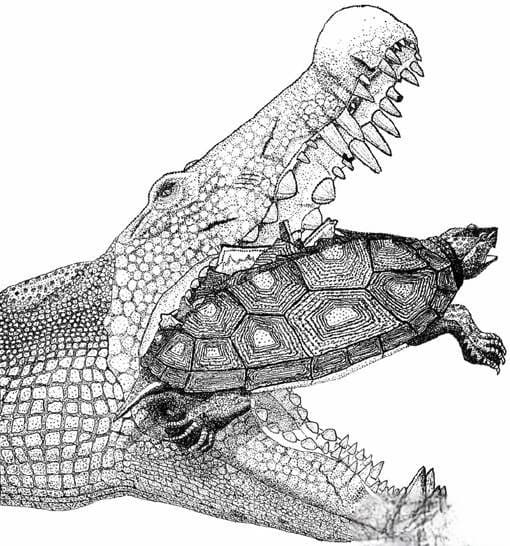

Head & snout: a broad, short snout that swells slightly toward the tip; robust, thick teeth, with shorter, blunter posterior teeth for crushing.

Continuity with modern forms: overall profile closely resembles living crocs, showing that the semi-aquatic ambush design was already highly optimized by the Late Cretaceous.

Bite force: biomechanical reconstructions indicate up to ~18,000 lbf (≈ 80,000 N)—far above measured values for the American crocodile (~2,125 lbf / ≈ 9,452 N).

Note: absolute numbers depend on reconstruction, but the conclusion of immense bite power is robust.

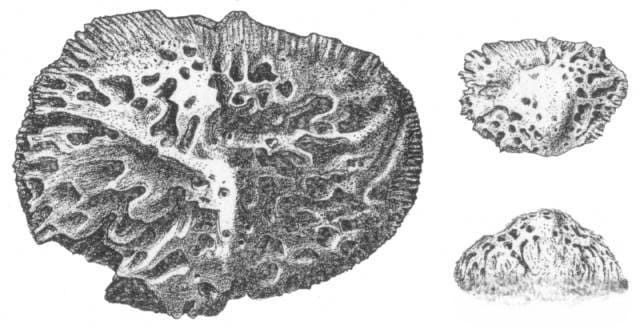

Osteoderms (bony scutes): thicker than in most living crocs; the back bore large, often semicircular scutes with pits and grooves interpreted as soft-tissue attachment sites. These could have stiffened and supported the trunk, useful for brief forays on land by such a massive animal.

Bony secondary palate: allowed breathing via nostrils above the water while the mouth and skull were submerged—ideal for stealthy ambush.

Vertebrae: procoelous (front concave, rear convex), forming ball-and-socket joints—a derived trait shared with modern crocodylians, supporting flexibility and maneuverability in water.

1999 – Erickson & Brochu:

Growth rings in dorsal osteoderms suggested ~35 years to reach full adult size, with some individuals possibly >50 years old.

2002 – Schwimmer (caution):

Rings may not strictly reflect annual cycles in the Mesozoic; prey migrations, wet–dry cycles, or currents might also imprint periodicity.

Takeaway: skeletochronology is informative but requires independent validation.

Deinosuchus material has been recovered from many U.S. states—Alabama, Mississippi, Montana, Georgia, New Jersey, North Carolina, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, Wyoming—and in 2006 an osteoderm was found in northern Mexico (first record outside the U.S.). Coastal plain deposits in Georgia (near the Alabama border) are especially rich.

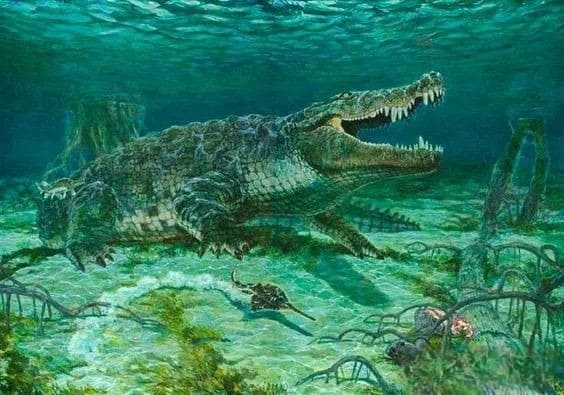

Paleoenvironment: occurrences cluster in estuaries, tidal flats, salt marshes, and near-shore settings; some fossils in marine strata likely represent foraging into coastal waters, much like today’s saltwater crocodiles.

Population pattern: larger, rarer individuals in western basins; smaller, more common in the east.

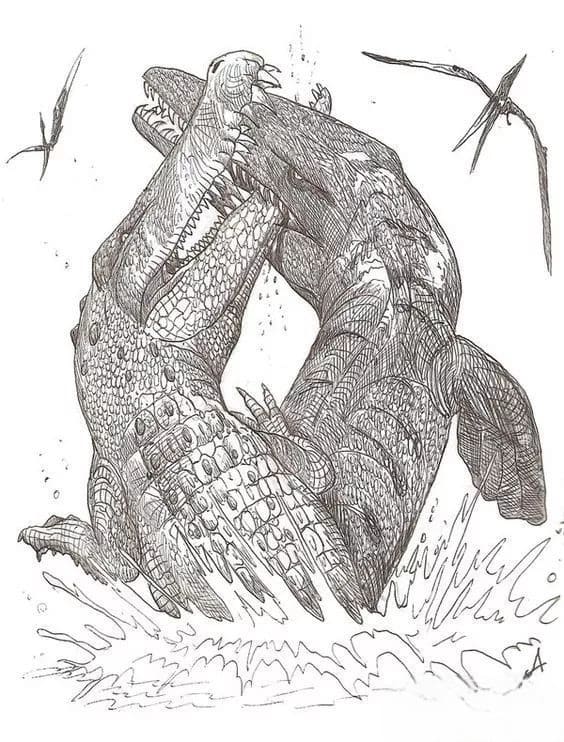

Likely hunting strategy: as with modern crocs, Deinosuchus lay submerged near banks, then exploded from cover to seize animals at the water’s edge, using dragging and drowning.

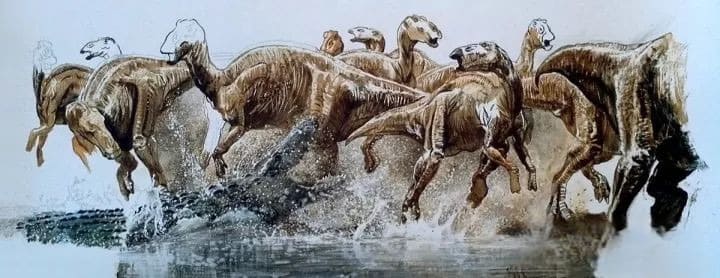

Trace evidence: hadrosaur (duck-billed dinosaur) caudal vertebrae with croc bite marks near Big Bend National Park support dinosaur predation/scavenging.

Regional nuance:

Eastern, smaller forms: an American-croc-like generalist, taking turtles, large fish, and small dinosaurs.

Larger western forms: more specialized on large dinosaur prey.

Trophic status: in some eastern localities, no theropod exceeded Deinosuchus in size, making it the probable apex predator.

With its mass, armor, and bite, Deinosuchus would dominate modern estuaries and deltas, threatening large ungulates, rival crocs, and even coastal marine mammals. Yet such gigantism also implies immense energy needs and strong dependence on stable wetlands, making it vulnerable to climate and hydrologic change.

A widely seen head model at the American Museum of Natural History used Cuban crocodile geometry plus plaster infill. Some researchers argue this is conservative, suggesting that saltwater crocodile proportions might yield a bulkier Deinosuchus reconstruction—one reason length/mass estimates diverge among teams.

Geologic age: Late Cretaceous (≈ 80–73 Ma)

Clade: Crocodylia (Alligatoroidea)

Range: Eastern & western North America; record also in N. Mexico

Length: ~8–12 m (conservative), up to ~15 m (extreme)

Mass: ~2.3 t (eastern) to ≥8.5 t (western), model-dependent

Bite force: ≈ 80,000 N (inferred)

Ecology: Semi-aquatic apex ambush predator at water margins

Prey: Large fish, turtles, and dinosaurs (trace evidence)

Skeletal traits: Heavy armor, secondary palate, procoelous vertebrae

Why giants thrive in estuaries

Nutrient delivery, abundant fish/reptiles, and turbid, structurally complex banks create ambush cover and dense prey flows—perfect for low-cost cruising + high-burst attacks.

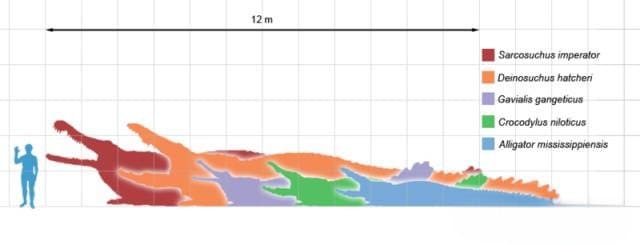

Deinosuchus vs. other giants

Compared with living Nile or American alligators, Deinosuchus is substantially larger. Versus the Jurassic/Cretaceous Sarcosuchus (“SuperCroc”), comparisons are complicated by different ages, habitats, and reconstruction methods—but both were top-tier crocodyliforms of their times.

Deinosuchus pushed the “croc design” to Cretaceous extremes: crushing dentition, fortress-like armor, and a body built for stealthy acceleration. The fossils may be fragmentary and the numbers debated, but one picture is clear—it was among the most formidable shoreline hunters the planet has ever seen.

animal tags: deinosuchus

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.