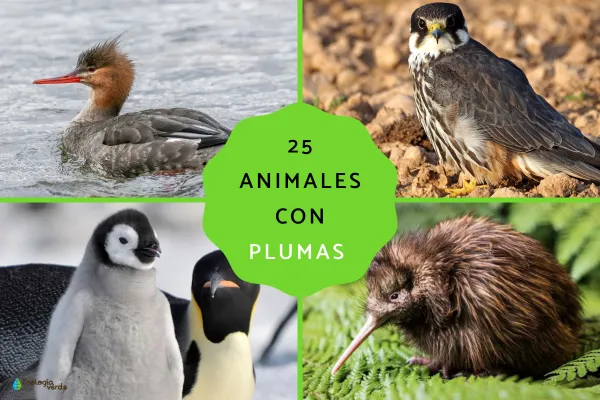

Earth’s biodiversity is astonishing—scientists estimate around 8.7 million species. While some prehistoric reptiles may have had feather-like structures, today only birds truly have feathers. In this guide, you’ll meet 25 feathered animals (all birds), with easy-to-read traits, behaviors, and habitats.

Quick fact: Feathers aren’t just for flight—they also insulate, waterproof, camouflage, signal to mates, and even help birds sense airflow.

What counts as an animal with feathers?

Feather types and what they do

Flying birds (15 examples)

Flightless birds (10 examples)

FAQs & takeaways

“Animals with feathers” are birds (class Aves)—vertebrates whose bodies are covered with feathers and whose forelimbs evolved into wings. Most can fly; some no longer do because of body plan, ecology, or evolution.

Two core traits (kid-friendly):

Feathers + wings: Wings create lift and control; feathers shape the body and the air around it.

Endothermy (warm-blooded): Birds keep a stable internal temperature—feathers are key for insulation.

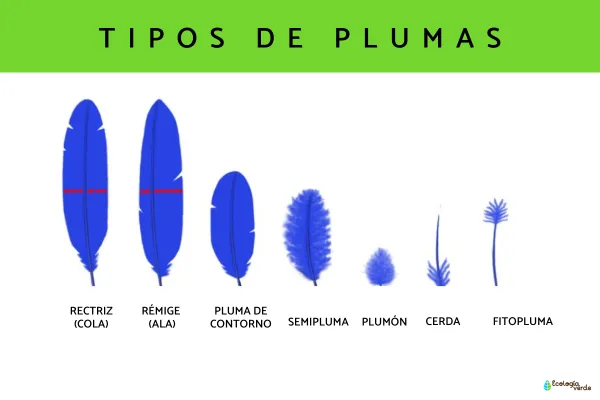

Flight feathers (remiges & rectrices): Stiff, often asymmetrical feathers on wings and tail; generate lift, thrust, and steering.

Contour feathers: Smooth outer “coat” that streamlines the body, sheds rain, and gives color/pattern.

Semiplumes: Soft feathers under the contour layer; add insulation and help shape the body.

Down (downy feathers): Fluffy layer close to the skin; excellent thermal insulation and buoyancy for waterbirds.

Filoplumes: Hair-like sensory feathers that help birds feel feather position and airflow.

Bristles: Stiff, whisker-like feathers around the beak (common in insect-eaters); aid tactile sensing and prey capture.

Pro tip: Many birds use oil from the uropygial (preen) gland to keep feathers clean, flexible, and water-resistant.

Woodpeckers (Family Picidae)

Reinforced skulls and chisel-like bills for drilling wood; long sticky tongues for extracting insects. Often boldly patterned; important for forest health (pest control, seed dispersal).

Cuckoos (Family Cuculidae)

Slender birds with long tails and pointed wings. Some species are famous brood parasites, laying eggs in other birds’ nests. Plumage typically gray or brown for camouflage.

House Sparrow — Passer domesticus

A city and farmstead regular worldwide. Sexual dimorphism: males are brighter and show a dark “bib” in breeding season.

Red-breasted Merganser — Mergus serrator

A diving duck with a narrow, serrated bill for gripping fish. Males show dark iridescent heads with a shaggy crest; females are reddish-brown. Fast flyers and agile divers.

Eurasian Hobby — Falco subbuteo

Small, swift falcon with pointed wings; hunts dragonflies and small birds on the wing. Breeds across Europe and Asia; winters in Africa.

Golden Eagle — Aquila chrysaetos

Large raptor with golden nape; feathered legs (“booted eagles”). Powerful stoops and broad wings make it a master of mountainous and open habitats.

Common Swift — Apus apus

Aerial specialists that feed, drink, and even sleep on the wing. Long, scythe-shaped wings; dark, sleek plumage; astonishing speed and stamina.

Indian Peafowl (Peacock ♂) — Pavo cristatus

Males display dramatic iridescent trains with “eye” spots for courtship; females are subtler brown. A classic example of sexual selection.

Hummingbirds (Family Trochilidae)

Tiny, high-energy fliers that hover and can fly backward thanks to unique shoulder joints. Nectar feeders and key pollinators; iridescent structural colors.

Superb Lyrebird — Menura novaehollandiae

Renowned for elaborate tail (“lyre-shaped”) and mimicry—can imitate other birds and environmental sounds. Native to Australian forests.

Flamingos — Phoenicopterus spp.

Pink hues come from carotenoids in algae and crustaceans. Long legs and filter-feeding bills suit shallow wetlands; highly social.

Macaws — Ara spp.

Large parrots with powerful bills for nuts and seeds; smart and long-lived. Pair bonds strong; plumage brilliantly colored.

Toucans (Family Ramphastidae)

Oversized, lightweight, colorful bills aid fruit handling, display, and heat exchange. Tropical forest canopy dwellers and seed dispersers.

Mandarin Duck — Aix galericulata

East Asian icon; males wear ornate “sail” feathers in breeding season. Prefers wooded lakes and slow rivers; pairs are tightly bonded.

Shoebill — Balaeniceps rex

Wetland specialist of East Africa with a massive shoe-shaped bill for lungfish and other prey. Slow, deliberate movements; prehistoric look.

Penguins — Family Spheniscidae

Forelimbs evolved into flippers; they “fly” underwater. Waddling on land, superb swimmers at sea; thick down and fat for insulation. Many breed in large colonies.

Ostrich — Struthio camelus

The largest living bird; males black-and-white, females gray-brown. Can’t fly but can sprint at highway speeds; wings help with balance and display.

Kiwi — Apteryx spp.

Endemic to New Zealand (not Australia). Tiny vestigial wings, hair-like feathers, and a long probing bill. Mostly nocturnal with keen smell.

Cassowary — Casuarius spp.

Large rainforest birds with blue necks, red wattles, and a hard casque. Mostly fruit-eating and crucial seed movers in tropical forests.

Kakapo — Strigops habroptilus

The world’s only flightless parrot, nocturnal and heavy-bodied; green mottled plumage for camouflage. Critically endangered; males display at communal leks.

Domestic Duck — Anas platyrhynchos domesticus

Descended from mallards; centuries of domestication reduced flight ability in many breeds. Highly adaptable with diverse varieties.

Chicken — Gallus gallus domesticus

Short bursts of flapping and gliding only. Feathers provide insulation and protection; strong social hierarchy in flocks.

Rheas — Rhea spp.

South American grassland giants, ostrich-like but smaller. Excellent runners; males incubate eggs and rear chicks.

Flightless Cormorant — Phalacrocorax harrisi

Restricted to the Galápagos Islands; tiny wings but powerful legs. Superb underwater pursuit hunters.

Kagu — Rhynochetos jubatus

New Caledonia endemic with elegant gray-white plumage and a fine crest. Ground-dwelling forest bird with loud, carrying calls.

Do all feathered animals fly?

No. Feathers evolved for multiple jobs. Flight requires specific aerodynamics and musculature; penguins, ostriches, cassowaries, kakapos, and others are flightless.

Why are feathers so water-resistant?

Feather micro-structure sheds water, and many birds apply oil from the preen gland while grooming to enhance waterproofing—vital for waterbirds.

Why are some birds so colorful?

Colors come from pigments (melanins, carotenoids) and structural color—microscopic feather structures that bend and scatter light (think peacocks and hummingbirds).

Do birds keep the same feathers forever?

No. Birds molt—they periodically replace worn feathers. Many also develop special breeding (nuptial) plumage for courtship displays.

You’ve met 25 feathered animals and learned how feathers work—from flight and warmth to waterproofing and display. For teaching kids, try organizing them by themes like “fliers vs. flightless” or “forest, wetland, city,” which makes learning visual and fun.

animal tags: animals with feathers

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.