Across the world’s freshwater ecosystems, rivers host a uniquely diverse—and sensitive—set of species. River fish depend on stable physico-chemical conditions (temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, nutrients) and, ecologically, they act like biological corridors and “semi-permeable membranes,” moving energy and matter through food webs and across habitats. Protecting river habitats and connectivity is therefore essential for freshwater biodiversity.

River-fish types & common classification schemes

River-fish name lists (by region)

10 of the largest river fishes worldwide

Fish that “run” upstream to spawn (migration 101)

“White fish” (lean): lower fat; many live in relatively stable or deeper waters and have lower routine energy demands.

“Blue/oily fish”: higher fat; often capable of long migrations or sustained activity and thus store more lipids and fat-soluble nutrients.

Note: “white vs. blue/oily” is a culinary shorthand; the biological reality is a gradient of lipid content across species and life stages.

Food fish (e.g., trout, sturgeon, catfish).

Ornamental fish (e.g., guppies Poecilia reticulata, angelfish Pterophyllum scalare).

Resident (complete their life cycle within river/lake systems).

Anadromous (grow at sea, run upstream to freshwater to spawn): e.g., salmon, some sturgeons, smelts.

Catadromous (grow in rivers, migrate to the sea to spawn): e.g., European eel.

Potamodromous (within-river-basin migrants): e.g., many South American characins such as prochilod (“sábalo”).

We retain representative species from the original lists and add brief context. Common names vary regionally; scientific names (italicized) are included for clarity.

River pipefish (Syngnathus abaster)

Andalusian barbel (Luciobarbus sclateri)

Quignard’s stone loach (Barbatula quignardi)

Brown trout (Salmo trutta)

European sturgeon (Acipenser sturio)

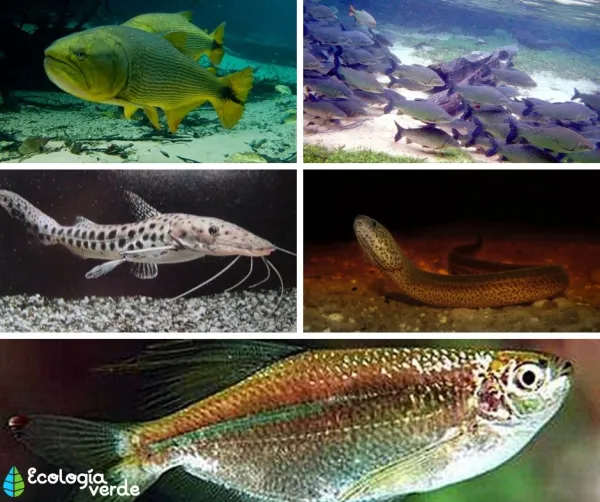

Golden dorado (Salminus brasiliensis)

Streaked prochilod / sábalo (Prochilodus lineatus) — a classic potamodromous migrant

Spotted sorubim (surubí) (Pseudoplatystoma corruscans)

Swamp eels (family Synbranchidae)

“Mojarras” (family Characidae, multiple genera of small characins)

Basketmouth cichlid (Acaronia nassa)

Doradid talking catfish (Amblydoras nauticus)

Landonia latidens (rare characin)

Rhamdia catfish (Rhamdia jequetepeque)

Black-tailed brycon (Brycon atrocaudatus)

Striped aplochiton (Aplochiton taeniatus)

Southern silverside (Basilichthys australis)

Common galaxias (Galaxias maculatus)

Maule silverside (Odontesthes mauleanum)

Zebra aplochiton (Aplochiton zebra)

Sizes vary widely with age and environment; the list below highlights iconic giant freshwater fish.

Arapaima / pirarucu (Arapaima gigas) — South America (Amazon basin)

Longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus) — North America

Mekong giant catfish (Pangasianodon gigas) — Asia (Mekong)

White sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) — North America

Beluga sturgeon (Huso huso) — Eurasia (Caspian–Black Sea drainages)

Ocellate river stingray (motoro) (Potamotrygon motoro) — South America

American paddlefish (Polyodon spathula) — North America (Mississippi basin)

Nile perch (Lates niloticus) — Africa

Taimen (Hucho taimen) — Asia

Bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) — primarily coastal marine, but capable of prolonged freshwater incursions (e.g., Amazon and other large rivers)

Many fishes undertake long, arduous migrations to reproduce, often swimming against strong currents, leaping obstacles, and timing their run with flows and temperature. Strategies differ:

Salmon (Salmo spp., Oncorhynchus spp.)

Sturgeons (e.g., Acipenser sturio)

European smelt (Osmerus eperlanus)

Gudgeon (Gobio gobio)—shorter migrations; riverine

European eel (Anguilla anguilla)—adults migrate to the Sargasso Sea to spawn; larvae drift back to continental waters as glass eels/elvers.

Note: Eels often appear in “upstream spawners” lists, but strictly speaking they spawn at sea and migrate into rivers to grow.

Prochilod / sábalo (Prochilodus lineatus)—large seasonal runs within South American basins

Pejerrey (silverside) (Odontesthes bonariensis)—regional movements; many populations are lake–river linked

Transparent goby / chanquete (Aphia minuta)—coastal/estuarine–river movements in some areas

Why migrate? To reduce competition with adults, optimize egg and larval survival (temperature, oxygen, substrate), and exploit seasonal productivity pulses. Migration also makes species sensitive to dams, low flows, and habitat fragmentation, which is why fish passages and environmental flows matter.

River fishes use diverse adaptations and life histories to keep river basins healthy—from shuttling nutrients across habitats to anchoring food webs. Because they’re highly sensitive to water quality, habitat integrity, and longitudinal connectivity, effective freshwater conservation must safeguard spawning grounds, migration corridors, and key refuges. Knowing who lives in our rivers is the first step to protecting them.

Bibliography

Sverlij, S. et al. (2007) Fishes of the Paraná-Paraguay River Corridor. Inventory of the wetlands of the Paraná-Paraguay River Corridor, pp: 341-352.

Correa, E. & Ortega, H. (2010) Diversity and seasonal variation of fishes in the lower Nanay River basin, Peru. Peruvian Journal of Biology, Volume 17 (1).

López, L. et al. (1987) Checklist of freshwater fishes of Argentina. Aquatic Biology, Volume 12, pp: 1-50.

Valdovinos, C. et al. (2012) Spatiotemporal dynamics of 13 native fish species in a lake-river ecotone of the Valdinia River basin (Chile). Gayana Concepción Journal, Volume 76 (1).

animal tags: river fish

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.