As the years go by, the number of animals facing extinction continues to rise. Some species may be more well-known than others, but each one plays an equally important role in maintaining the balance of ecosystems. The loss of biodiversity is an undeniable reality, and human activities are a major driving force behind it.

Among the most threatened species is the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), whose situation is particularly dire. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies it as Critically Endangered (CR)—meaning it faces an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild. Once widespread across Asia, this massive mammal now survives only in a single location: Ujung Kulon National Park on the western tip of Indonesia’s Java Island.

This article explores the Javan rhino’s unique characteristics, the reasons for its decline, and the conservation measures that could help save it from disappearing forever.

Population status:

Only about 67 individuals remain in the wild, all within Ujung Kulon National Park.

The population is small, fragmented, and still declining.

Behavior and habitat:

Solitary by nature, preferring the dense cover of tropical rainforests.

Because of its elusive habits, it is one of the least studied rhino species. Most data comes from dung analysis, camera trap images, and specimens in zoos or museums.

Physical traits:

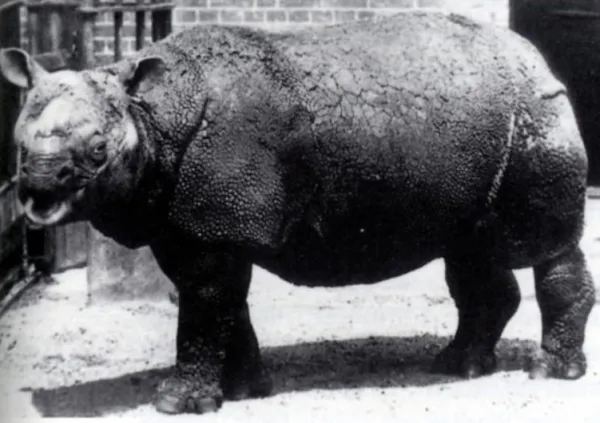

Thick, grey-brown skin with deep folds, giving it an armor-plated appearance.

Large body size, weighing 800 kg to 2.5 tonnes and standing up to 2 meters tall.

Females are typically slightly larger than males.

A single front horn, measuring up to 25 cm in length.

Diet and lifespan:

Strictly herbivorous, feeding on leaves, shoots, and aquatic plants.

Life expectancy of up to 50 years.

The Javan rhinoceros has been listed as Critically Endangered since 1996, with multiple threats driving its decline:

Historically ranged across Sumatra, Java, Southeast Asia, western India, and southern China.

Targeted for its horn, which is highly valued in traditional medicine—particularly in Asia—where powdered horn is wrongly believed to treat fever, detoxify the body, and even help with cancer.

Despite legal protection, illegal hunting still occurs.

With just 67 individuals, the species has an extremely limited gene pool.

Many surviving rhinos are elderly and may no longer be capable of reproduction.

Deforestation for timber, intensive rice cultivation, and expanding human settlements have drastically reduced its range.

Today, it occupies only a small corner of Java Island.

Java is prone to earthquakes and volcanic activity.

In 2018, the eruption of Anak Krakatoa volcano triggered a tsunami, threatening human lives and wildlife alike.

Although the Javan rhino population was not directly harmed, future disasters could devastate the entire species in one event.

Efforts to save the Javan rhinoceros include:

Legal Protection

Fully protected by law in all range states since 1975.

Ranger Training and Equipment

Professional park rangers patrol to prevent poaching.

Use of GPS tracking, microchips, and monitoring programs to safeguard individuals.

Habitat Expansion and Ecological Corridors

Creating new protected areas for breeding and foraging.

Establishing corridors to connect habitats, enabling safer movement.

Public Engagement

Avoid purchasing illegally sourced timber, agricultural goods, or wildlife products.

When visiting the park, avoid disturbing wildlife and damaging the environment.

Report poaching or illegal trade to authorities.

Support conservation groups through donations or volunteer work.

The Javan rhinoceros is not only one of the rarest large mammals on Earth but also a vital part of its ecosystem. Protecting it means safeguarding the rich biodiversity of Southeast Asia’s rainforests for future generations.

animal tags: javan rhinoceros

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.