Aquatic insects are invertebrate arthropods that live primarily in freshwater habitats. More than 76,000 aquatic insect species are known. Representative examples include the great silver water beetle (Hydrophilus piceus), diving beetles (Dytiscidae), haliplids (Haliplidae), and hygrobiids (Hygrobiidae).

If you’d like to learn what aquatic insects are, how many kinds exist, their key adaptations and ecological roles—plus notable groups and examples—read on.

What are aquatic (water) insects?

How many kinds of aquatic insects exist?

What adaptations do aquatic insects have?

What roles do aquatic insects play?

Notable groups and examples

Water striders (Gerridae)

Great silver water beetle (Hydrophilus piceus)

Whirligig beetles (Gyrinidae)

Burrowing water beetles (Noteridae)

Hygrobiid beetles (Hygrobiidae)

Water boatmen (Corixidae)

Haliplid beetles (Haliplidae)

Riffle beetles (Elmidae)

Giant water bugs (Belostomatidae)

Diving beetles (Dytiscidae)

Aquatic insects are arthropods that live mainly in freshwater—puddles, ponds, ditches, streams, and lakes—where they often go unnoticed. Only a very small number are marine.

Special cases include open-ocean water striders (genus Halobates, order Hemiptera) and marine-associated caddisfly larvae (family Chathamiidae). Overall, aquatic insects occupy nearly every freshwater ecosystem and microhabitat known.

There are about 76,000 species of aquatic insects—roughly 8% of all insects—found in lakes, rivers, streams, estuaries, and temporary pools.

While most species are freshwater, a few thousand occur in marine or brackish settings, especially among beetles, true bugs, flies, and mosquitoes.

Importantly, five insect orders have aquatic immature stages but typically terrestrial or aerial adults: mayflies (Ephemeroptera), dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata), stoneflies (Plecoptera), megalopterans (Megaloptera), and caddisflies (Trichoptera).

Aquatic insects show remarkable adaptations that allow them to breathe, move, and feed underwater:

Respiration

Simple diffusion across a thin cuticle.

Air bubbles carried beneath the body or elytra as temporary “scuba tanks.”

Plastrons (a permanent, air-retaining film held by hydrophobic hairs) enabling continuous gas exchange.

Tracheal gills (filamentous or plate-like extensions) in many larvae.

Siphons acting like snorkels to access surface air.

Hemoglobin-based oxygen storage in some larvae (e.g., certain midges) for low-oxygen habitats.

Locomotion & form

Streamlined, flattened, or spindle-shaped bodies to reduce drag.

Oar-like hind legs fringed with swimming hairs for propulsion.

Hydrophobic microhairs to shed water, carry air, or skate on the surface.

Life history

Many species are aquatic as larvae/nymphs but terrestrial or aerial as adults, reducing competition between life stages and expanding resource use.

Decomposition & nutrient cycling: Larvae/nymphs consume algae, detritus, and fine organic matter, speeding breakdown and recycling.

Key links in food webs: They are vital prey for fish, amphibians, and waterbirds, connecting primary producers to top predators.

Water clarity & sediment oxygenation: Filter-feeders remove suspended particles; burrowers mix surface sediments, improving oxygen penetration.

Population control: Predatory insects (e.g., diving beetles, giant water bugs) regulate other invertebrates.

Bioindicators: Community composition reflects water quality (temperature, oxygen, nutrients, pollution). Aquatic insects are widely used in freshwater biomonitoring.

Also called: pond skaters.

Where: chiefly on the surface of inland waters (rivers, lakes); genus Halobates includes rare pelagic marine species.

Diversity: 1,700+ species.

Traits: Long, slender legs covered with hydrophobic hairs allow them to skim the water surface without sinking.

Size: up to 5 cm, among the largest aquatic beetles.

Look: glossy black with a green sheen, bulging eyes, reddish antennae.

Habitat: lakes, ponds, marshy ditches.

Range: western Palearctic—from Scandinavia to India/China and North Africa.

Size: 3–15 mm; about 800 species worldwide.

Behavior: Swim rapidly in whirling groups on the surface.

Traits: Divided eyes for simultaneous above- and below-water vision; forelegs seize prey, hind legs act as paddles.

Size: 1–5 mm; small, oval, brownish.

ID features: a distinctive noterid plate and a subtriangular sternal plate.

Habitat: lentic (still) waters with vegetation; adults and larvae breathe atmospheric air, so they frequent the surface.

Distribution: global, most common in the tropics.

Composition: a single genus, Hygrobia, with 6 living species (Europe, North Africa, China, Australia).

Size: 8–11 mm; oval to elongate body, prominent eyes, filiform antennae.

Habitat: stagnant waters, living in mud and detritus.

Diversity: ~500 species in 55 genera, worldwide.

Where: ponds and slow-flowing rivers; swim near the bottom.

Traits: elongate, flattened body (to 15 mm), triangular head, oar-like hind legs.

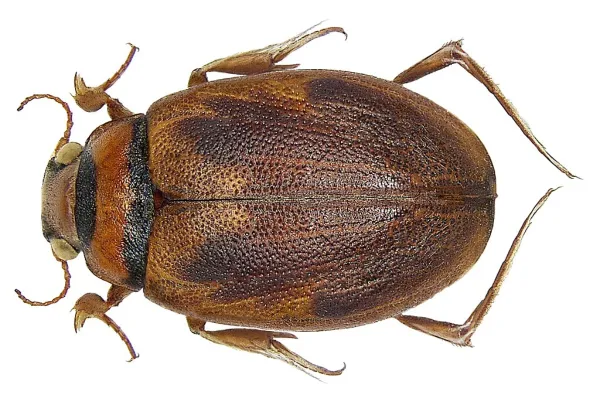

Size: 1.5–5 mm; small, oval, convex; yellowish to light brown.

ID feature: enlarged posterior coxal plates that store air.

Habitat: among vegetation in ponds, lakes, and streams.

Diversity: ~200 species, worldwide.

Diversity: 150+ genera and 1,500+ species, worldwide.

Ecology: Both adults and larvae are aquatic; prefer clear, fast-flowing streams with gravel, rocks, algal mats, and woody debris.

Traits: adults with filiform antennae; larvae elongate with filamentous gills.

Size: can exceed 12 cm, the largest hemipterans.

Habitat: ponds, marshes, and slow freshwater.

Traits: flattened, oval bodies; raptorial forelegs; abdominal breathing tube.

Distribution: worldwide; especially diverse in the Americas and East Asia.

Diversity: 5,000+ species worldwide.

Size: 2–45 mm; streamlined, hydrodynamic bodies; hind legs flattened with swimming hairs.

Ecology: carnivorous, strong swimmers; must surface to breathe.

Aquatic insects span filter feeders, shredders, grazers, and predators, forming the functional backbone of freshwater ecosystems.

Because they respond quickly to environmental change, they’re indispensable bioindicators in water-quality assessments.

When observing in the field: do not overturn rocks indiscriminately, disturb nests, or release non-native species. Joining local stream monitoring or citizen-science projects is a great way to start.

If you want to go deeper, begin with common local groups such as water striders (Hemiptera) and aquatic beetles (diving, whirligig, haliplid). Learn to identify them by body shape, legs, antennae, and habitat, and track seasonal changes in their abundance and behavior.

Bibliografía

Andersen, N.M y Cheng, L. (2004). The marine insect Halobates (Heteroptera: Gerridae): biology, adaptations, distribution, and phylogeny. En: Gibson, R.N., Atkinson, R.J.A. y Gordon, J.D.M. (Eds.). Oceanography and Marine Biology, An Annual Review Vol. 42, CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp. 119–179.

Archangelsky, Miguel & Michat, Mariano. (2014). Haliplidae. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264238866_Haliplidae

Michat, Mariano & Archangelsky, Miguel. (2014). Gyrinidae. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264238862_Gyrinidae

Urcola, Juan & Michat, Mariano. (2023). Noteridae. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375702027_Noteridae

Voshell, R., et al. (2025). Sustaining America's Aquatic Biodiversity - Aquatic Insect Biodiversity and Conservation. https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/420/420-531/420-531.html

White Earth Lab. (2021). Aquatic Insects: identification, examples, and use as bioindicators. https://wildearthlab.com/2021/06/27/aquatic-insects-identification/

animal tags: aquatic insects

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.