Across the animal kingdom, body plans vary wildly: some lineages rely on internal skeletons made of bone or cartilage, others on external skeletons, and many have evolved hard coverings for defense, support, and movement. One of the most successful of these adaptations is the shell—a tough structure that can be part of the skeleton itself or a hardened outer coat.

Below is a clear, biology-accurate guide to what “shells” are, how they differ among major groups, and representative animals you’re likely to encounter.

In zoology, “shell” broadly refers to a rigid protective structure that supports the body and shields soft tissues. It can arise in two very different ways:

In vertebrates, the skeleton is inside the body. In a few groups—most famously turtles—that internal skeleton expands outward and fuses with other bones to form a true shell that’s part of the skeleton. This shell does not molt.

Many invertebrates build a stiff outer skeleton. Its main materials are:

Chitin (a tough biopolymer) often mineralized with calcium salts (e.g., crustaceans, insects).

Calcium carbonate secreted in layers (e.g., mollusks), commonly called a “shell” or “conch”.

Because an exoskeleton can’t expand, these animals must molt (shed) it to grow.

Turtles are the only vertebrates whose shell is a direct extension of the skeleton. It has three parts:

Carapace (top shell)

Plastron (bottom shell)

Bridge (lateral connection between the two)

Anatomically, the shell incorporates ribs and vertebrae that have expanded and fused; outside, it’s often clad in keratin scutes (the patterned plates you see). It never molts.

Land tortoises (e.g., the Hermann’s tortoise, Testudo hermanni) typically have a high domed shell to resist bites and being flipped.

Aquatic and marine turtles (e.g., the loggerhead, Caretta caretta; the red-eared slider, Trachemys scripta elegans) have flatter, streamlined shells to reduce drag and swim efficiently.

Other roles: thermoregulation (basking vs. cooling), mineral storage, and—by retracting head and limbs—last-resort defense.

Mollusks are soft-bodied animals that typically protect themselves with a shell secreted by the mantle. The shell is layered calcium carbonate (aragonite/calcite) and can include a pearly inner layer. It prevents mechanical damage and buffers acidity in the environment.

Major shell-bearing groups:

Single, spiral shell, usually right-handed in opening.

Terrestrial, freshwater, and marine species; diets range from plant-eating to predatory and detritivory.

Two hinged valves closed by one or two powerful adductor muscles and a ligament.

Mostly filter feeders that help clarify waters (e.g., mussels—family Mytilidae; oysters—Ostreidae; many clams—Veneridae).

Pearls form when layers of nacre coat an irritant inside the shell.

The chambered nautilus (Nautilus spp.) retains a planispiral, partitioned outer shell used for buoyancy control.

Squids, cuttlefishes, and octopuses have reduced internal shells (e.g., the cuttlebone) to maximize agility.

Crustaceans (a branch of arthropods) wear a chitin-based exoskeleton often reinforced with calcium salts. The fused head-thorax is capped by a rigid carapace. Growth requires molting; freshly molted individuals are soft and vulnerable.

Representative crustaceans you’ll meet:

Crabs (many families): broad carapaces, powerful claws.

Shrimps/prawns: lighter, more agile exoskeletons, excellent swimmers.

Norway lobster / scampi (Nephrops norvegicus), often called cigala in Mediterranean markets.

European lobster (Homarus gammarus) and spiny lobsters (family Palinuridae).

Mantis shrimps (stomatopods; Mediterranean “galera”): heavily armored forelimbs adapted for “punching” or “spear” strikes.

Why it works: attachment sites for strong muscles, armor against predators, reduced water loss on land for some groups, and hydro/air-dynamic shaping.

Not all “shells” are the same. Below, we note the material and origin so you can see the difference at a glance.

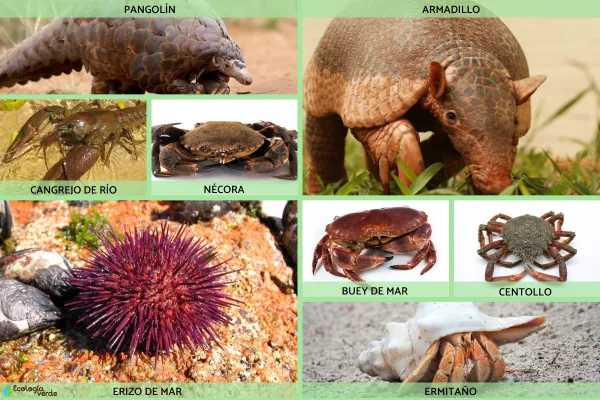

Pangolins (mammals) — body covered in keratin scales; roll into a ball for defense (armor-like, not a true shell).

Armadillos (mammals) — bony dermal plates overlain with keratin; some species can ball up.

Freshwater crayfish / “crawfish” (crustaceans) — classic mineralized exoskeleton.

Velvet crab (Necora puber) — small, active littoral crab with a tough carapace.

Sea urchins (echinoderms) — rigid calcareous test (fused plates) bristling with movable spines; unique jaw apparatus (“Aristotle’s lantern”).

Brown/edible crab (Cancer pagurus) — wide, heavy carapace; very strong claws.

Spider crabs (e.g., Maja spp.) — long-legged; carapace often camouflaged with algae.

Hermit crabs (crustaceans) — soft abdomens housed in borrowed snail shells (a “swap-out” protective shell).

True shrimps/prawns (crustaceans) — streamlined exoskeleton with dorsal carapace.

Cockroaches (insects) — chitinous exoskeleton; forewings hardened (tegmina) for extra protection.

Beetles (incl. ladybirds/ladybugs) (insects) — hardened forewings (elytra) act like armored covers for the hindwings and back.

Fleas (insects) — compressed bodies and a durable exoskeleton; powerful springing hind legs.

Ticks (arachnids) — robust cuticle and specialized mouthparts for hematophagy.

Woodlice / pillbugs (isopod crustaceans) — terrestrial crustaceans; some can roll into a ball (convergent defense).

Turtles (reptiles) — the archetypal bone-based shell (carapace + plastron).

Sea snails & conchs (mollusks) — calcium-carbonate shells of many forms.

Land snails (mollusks) — single spiral shell; moisture control and predator defense.

Ladybird/ladybug (beetle) — iconic spotted elytra with clear warning coloration.

“Shell” is a function, not a single design: turtles fuse bone into a shell; mollusks secrete calcium-carbonate shells; arthropods build chitinous exoskeletons.

Despite different origins, shells converge on the same benefits: defense, structural support, movement efficiency, hydration control, and sometimes mineral storage.

Knowing what the shell is made of tells you a lot about how the animal grows, molts, repairs, and survives in its habitat.

Bibliography

Ponder & Lindberg (1997). Towards a phylogeny of gastropod molluscs; an analysis using morphological characters. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 119: 83-101.

S. Gordillo (1995). Austral Molluscs: An Illustrated Guide. Zaguier and Urruty Publications, Buenos Aires. p. 115.

T. Hirasawa, H. Nagashima & S. Kuratani (2013) The endoskeletal origin of the turtle carapace. Nature communications, 4.

animal tags: animals with shells

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.