The ocean, the cradle of life on Earth, is home to countless mysterious and little-known creatures. Among them, sea spiders stand out as ancient aquarium/52-marine-animals.html">marine animals with fascinating adaptations and a history dating back over 500 million years. If you’re curious about these “oceanic spiders,” this guide will explain what sea spiders are, their unique characteristics, habitat, feeding habits, and reproductive strategies—all essential for enthusiasts, students, or anyone intrigued by the wonders of marine biology.

Sea spiders are not true spiders, but rather marine arthropods belonging to the class Pycnogonida. Here’s what makes them remarkable:

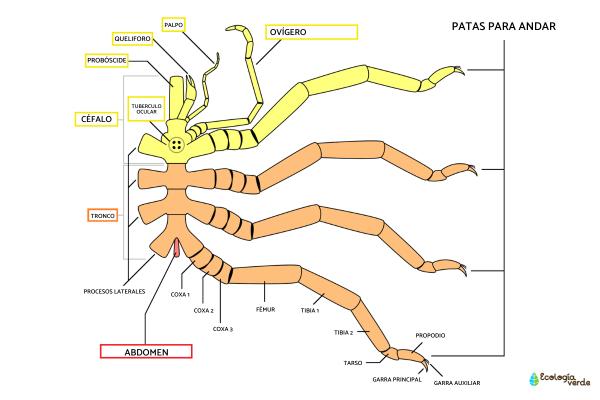

Body Structure: Sea spiders have highly reduced bodies with most of their mass in their long, slender legs—hence the nickname “all legs” (Pantopoda). Their body segments (head, thorax, and abdomen) are mostly fused, creating a compact form.

Appearance: Most species are brownish, blending into seaweed and rocks, while those in coral reefs often have brighter colors for camouflage.

Number of Legs: Typically, they have three or four pairs of elongated legs, and some deep-sea species can have legs reaching up to 50 centimeters (20 inches).

Mouthparts: Instead of fangs or mandibles, sea spiders possess a tubular proboscis (rostrum) used to suck fluids from their prey.

Respiration: Lacking gills or lungs, sea spiders absorb oxygen directly through their thin body surface.

Size: Most sea spiders are tiny—usually less than 1 centimeter long—though some deep-sea giants can measure up to 6 centimeters, with massive leg spans.

Are Sea Spiders Venomous?

Unlike many land spiders and scorpions, sea spiders do not have venom glands or stingers. Their proboscis is purely for feeding—piercing soft-bodied animals and drawing out fluids.

Sea spiders are entirely aquatic, found in a vast range of marine environments:

Global Distribution: These creatures are cosmopolitan, living in all of the world’s oceans—from the intertidal zone and shallow coastal waters to the deepest ocean trenches (down to 7,000 meters/23,000 feet).

Adaptability: Deep-sea species often show "gigantism," a phenomenon where individuals reach much larger sizes in cold, deep environments. The Antarctic species Colossendeis megalonyx, for example, has a leg span of half a meter.

Sea spiders use their specialized proboscis for a unique way of feeding:

Feeding Apparatus: Their proboscis is lined with fine bristles and acts like a syringe, piercing the bodies of prey to suck up nutrients.

Diet: They mainly consume soft-bodied marine invertebrates, including sponges, coral polyps, sea anemones, jellyfish, and polychaete worms.

Feeding Behavior: Sea spiders often move slowly along the seafloor or among coral, using their long legs to maneuver and their proboscis to feed discreetly on soft tissue or body fluids.

Sea spiders have separate sexes in most species, with only a few hermaphroditic exceptions.

Reproduction: Fertilization is external—males and females release their gametes into the water, and eggs are fertilized outside the body. Both males and females can have "ovigers" (special appendages) for carrying eggs, but males usually assume the main parental role.

Paternal Care: One of the rarest traits among invertebrates is paternal care. Male sea spiders attach fertilized eggs to their ovigers, tending and protecting them until they hatch.

Larval Development: Hatchlings emerge as tiny, simple larvae called protonymphs, which gradually develop their segmented bodies and legs. Some remain attached to the father, some live freely, and others may develop as parasites inside other marine invertebrates.

Sea spiders (class Pycnogonida) are among the most ancient and widespread marine arthropods, uniquely adapted to diverse underwater ecosystems. With their unusual body structure, distinctive feeding style, and remarkable paternal care, they play a subtle but important role in ocean food webs. Whether you’re a marine enthusiast or a curious reader, sea spiders offer a fascinating glimpse into the evolutionary wonders of ocean life.

Bibliography

Beatty, R., Beer, A., & Deeming, C. (2010). The Book of Nature. Great Britain: Dorling Kindersley.

ScienceDirect. (2022). Pycnogonida – an overview. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/pycnogonida

Myers, P. (2001). "Pycnogonida." Animal Diversity Web. Available at: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Pycnogonida/

animal tags: sea spiders Pycnogonida sea spider facts marine arthropods sea spider habitat sea spider diet deep sea animals ocean invertebrates

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.