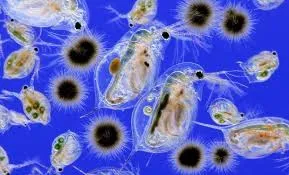

When we swim in a lake or the sea, we often wonder what kinds of animals and plants might live there. Some, like fish or crabs, are visible to the naked eye. But if we could look at the water through a microscope, we would discover a hidden universe of tiny organisms drifting with the currents—this is plankton.

Though almost invisible, plankton plays a fundamental role in sustaining life on Earth and regulating the planet’s ecosystems. Let’s explore what plankton is, its types, and why it is so important.

The term plankton was first coined by German scientist Victor Hensen in 1887 to describe the multitude of organisms that drift passively in aquatic environments. The word comes from the Greek “planktos,” meaning wandering or drifting.

Plankton is incredibly diverse, found in both freshwater and marine ecosystems. It is most abundant in the oceans, where its populations number in the trillions, especially in colder seas. In freshwater, plankton is usually concentrated in still waters such as lakes, reservoirs, and ponds, since in flowing rivers or streams they are often washed away.

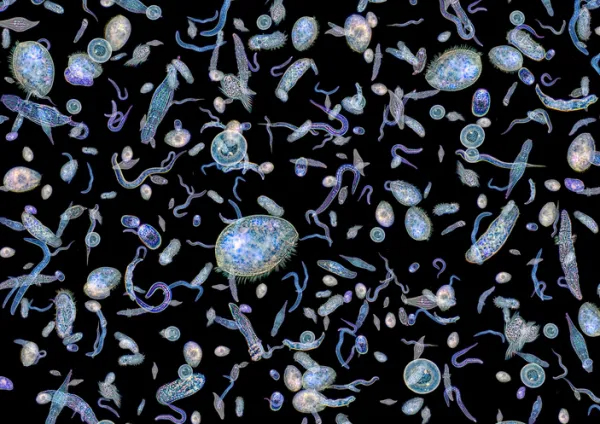

Plankton can be classified by feeding strategy or size.

Phytoplankton (plant-like plankton)

Function like plants, using photosynthesis to produce energy and organic matter.

Found in the sunlit photic zone of the ocean (up to 200 meters deep).

Includes cyanobacteria, diatoms, and dinoflagellates.

They are the foundation of marine food webs and generate nearly half of Earth’s oxygen.

Zooplankton (animal-like plankton)

Holoplankton – planktonic for their entire life cycle.

Meroplankton – planktonic only during the larval stage.

Feed on phytoplankton or other zooplankton.

Includes tiny crustaceans (copepods), jellyfish, and fish larvae.

Can be:

Bacterioplankton (bacterial plankton)

Communities of bacteria.

Decompose organic matter and play a crucial role in biogeochemical cycles (carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, oxygen).

Virioplankton (viral plankton)

Aquatic viruses, including bacteriophages and those infecting algae.

Help recycle nutrients and regulate plankton populations.

Ultraplankton: ~5 microns (bacteria, tiny flagellates).

Nanoplankton: 5–60 microns (unicellular algae, small diatoms).

Microplankton: 60 microns–1 mm (larger diatoms, dinoflagellates, copepods, mollusk larvae).

Mesoplankton: 1–5 mm (fish larvae).

Macroplankton: 5 mm–10 cm (sargassum seaweed, salps, jellyfish).

Megaplankton: Over 10 cm (large jellyfish).

To remain afloat, many plankton species have developed unique adaptations: increasing body surface area, storing fat droplets for buoyancy, or shedding heavy body parts. Some species even change their body shape seasonally to survive different water conditions.

Despite their microscopic size, plankton supports life on Earth in several crucial ways:

Phytoplankton convert sunlight into energy and organic matter.

Zooplankton feed on phytoplankton and are, in turn, eaten by fish, whales, seabirds, and other predators.

Bacterioplankton and virioplankton recycle nutrients, ensuring the cycle of life continues.

Together, they form the foundation of aquatic food webs, supporting nearly all marine and freshwater ecosystems.

Plankton are extremely sensitive to environmental changes, making them excellent bioindicators of water quality and pollution levels. For example, Daphnia (water fleas) are widely used in toxicity studies to assess the impact of contaminants on aquatic ecosystems.

Bacterioplankton are central to the cycling of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur.

Photosynthetic plankton, including cyanobacteria, produce about 50% of Earth’s oxygen, significantly reducing greenhouse gases.

When plankton die, they sink to the seafloor and form sediments that, over millions of years, give rise to oil and natural gas deposits.

Plankton contributes to climate regulation through the production of dimethyl sulfide (DMS).

DMS is released when phytoplankton break down, eventually entering the atmosphere.

There, it forms sulfate aerosols that help seed clouds.

Clouds reflect sunlight, cooling the Earth and reducing the greenhouse effect.

This natural mechanism demonstrates how even microscopic organisms can influence global climate patterns.

Plankton may be tiny, but they are giants of the biosphere:

They sustain the global food chain.

They regulate vital chemical cycles.

They produce oxygen and help stabilize the climate.

They even contribute to energy resources over geological time.

Without plankton, life on Earth as we know it would not exist. Understanding and protecting these small but mighty organisms is essential for maintaining the balance of our planet’s ecosystems.

animal tags: plankton

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.