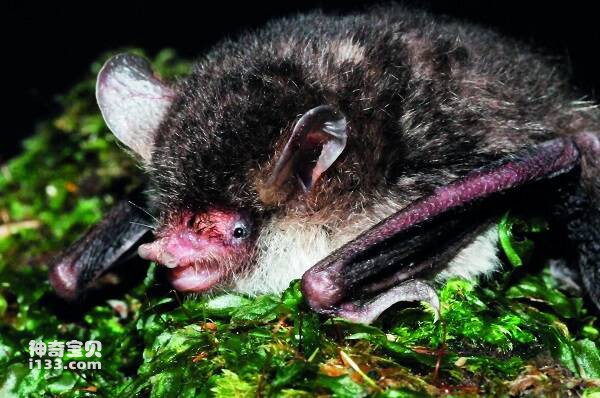

Chinese Horseshoe Bat

IUCN

LCBasic Information

Scientific classification

- name:Chinese Horseshoe Bat

- Scientific Name:Chinese Horseshoe Bat, Chinese Rufous Horseshoe Bat

- Outline:Chiroptera

- Family:Pterodactyla Chrysopteridae Chrysopterus

Vital signs

- length:41-53mm

- Weight:

- lifetime:

Feature

Small eyes and big ears, host of new coronavirus, host of SARS

Distribution and Habitat

In China, it is distributed in provinces south of the Yangtze River (including Hong Kong and Hainan) and Shaanxi, Gansu and Tibet. It is distributed abroad in India, Myanmar, Nepal and Vietnam.

The Chinese horseshoe bat lives at altitudes between 500 and 2769 m. In South Asia, the species is commonly found in mountainous forests with heavy rainfall. They inhabit caves, abandoned old tunnels, temples, houses, dry Wells, and hollows in trees. In Nepal, they have been found in any cave in the forest far from human activity. In central Vietnam, samples of the species were found in a cave surrounded by degraded forest and farmland at an altitude of 650 meters. In northern Myanmar, the species is recorded in dense tropical moist forests and also survives in some bamboo forests.

Appearance

Medium size. The forearms are 45-52mm long and the cranial length is 19-23mm. The horseshoe leaf in the nose leaf is larger, and the lower edge of both sides has a small attached leaf, the left and right sides of the saddle leaf are parallel, and the tip of the connecting leaf is broad and smooth. The back hairs are chestnut, the base grey, and the belly hairs are ochre brown.

Details

The Chinese Rhinolophus rouxii sinicus was previously classified as a subspecies of Rhinolophus rouxii sinicus (Chinese name for Rhinolophus rouxii sinicus) until 1997. Due to chromosome and morphological studies, it is very different from Rhinolophus lui, so it was promoted to a separate species in 2012.

The Chinese horseshoe bat can be integrated into a colony of hundreds of individuals, and has been seen to live in the same cave as the Pieteri's Bat, the Southwest Myoear bat, the great hoofed bat, the long-winged bat, and the Chinese Myoear bat. Mostly nocturnal, most rely on their unique echolocation ability to determine the location of external objects and themselves. The high-frequency waves emitted by the mouth or nose can reach 30-100 KHZ, and the sound waves reflected by external objects can be received by the bat's ears. The flight speed is about 15-50 km/h. The flight speed of the narrow and long wing membrane is higher than that of the wide and short wing membrane. Insectivorous or herbivorous and blood-sucking.

Usually mating in autumn, sperm in the female reproductive tract over winter, until late spring and early summer of the next year to give birth. The female has a pair of mammary glands and two "false nipples" above and to the side of the genital opening, to which the newborn bats attach a few days after birth. The young grow to sexual maturity the following autumn.

In November 2002, a deadly new virus suddenly appeared in southern China. In less than a year, the disease it caused, known as SARS, spread to 33 countries, sickened more than 8,000 people and killed more than 700. And then it disappeared. Now, for the first time, researchers say they have isolated a closely related virus from bats in China that can infect human cells. "This suggests that in China, there are now bats carrying viruses that can directly infect people and cause another SARS pandemic."

Scientists have long suspected that bats are a natural reservoir for coronaviruses, such as the one that causes SARS (Severe acute respiratory Syndrome). These animals have been identified as the source of many dangerous viruses, such as Nipah and Hendra, and have also been linked to Ebola and the novel coronavirus that causes a SARS-like illness, known as MERS.

In September 2005, four Rhinolophus species were identified, namely R. sinicus, R. ferrumequinum, R. macrotis, and R. Pidson II. They are the natural host of the SARS coronavirus, the causative agent of SARS. The disease broke out in 2002-2004.

Yet another study of the novel coronavirus is out, again pointing to bats as the source of the virus. This study was completed by Shi Zhengli's team at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The team published an article on the academic platform bioRxiv preprint on January 23, describing the 2019 novel coronavirus and related research results. Through data analysis, the genome sequence similarity between the 2019 novel coronavirus and the SARS virus that broke out in 2003 was 80%. It had the highest similarity with the related genome sequence collected from bats in China in February 2017, with a similarity of 88%.

According to Shi Zhengli's team, the team obtained the whole genome of the virus from the early five patients with the new coronavirus, of which the genomes of these five cases are basically identical, and the sequence consistency of the SARS virus is 79.5%.

What's more, Shi's team found that the sequence of the novel coronavirus was as high as 96 percent consistent with that of a bat coronavirus. By comparing the seven conserved non-structural proteins, it was found that the novel coronavirus was a coronavirus. In addition, the receptor for the novel coronavirus to enter the cell was ACE2, the same as that of the SARS virus.

In fact, in 2003, after the SARS outbreak, many acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronaviruses were found in bats, their natural host. Previous studies have shown that some of these SARSR-CoVs have the potential to infect humans. In November 2017, Shi's team published a paper in the journal PLos Pathgens in which they found more direct evidence that SARS-related viruses in bats are ancestors of human SARS viruses, after collecting samples from horseshoes bats in a cave in Yunnan Province for five years.