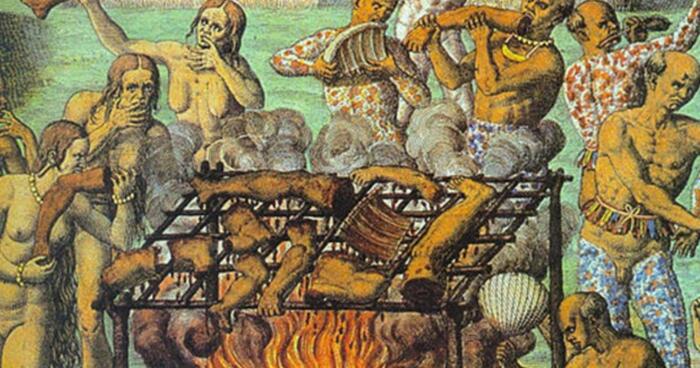

Did you know that cannibalism exists in the animal kingdom? It’s true! Many creatures, from insects to mammals, engage in this behavior for various reasons, and it's not just for survival. Sometimes it's about dominance, ensuring reproductive success, or even population control. Cannibalism in the wild might sound like something out of a horror movie, but for animals, it’s a necessary part of life.

In this article, we’ll explore fascinating and shocking facts about cannibalism in animals. From the praying mantis devouring its mate to polar bears facing harsh Arctic conditions, these facts will leave you amazed and intrigued by the darker side of nature.

Cannibalism, or the act of eating one’s own species, is more common in the animal kingdom than you might think. It occurs across a wide range of species and serves different purposes in different environments. Whether it’s reducing competition for food or ensuring that only the fittest offspring survive, cannibalism is nature’s way of maintaining balance in ecosystems.

Let’s dive into the details and learn more about this intriguing phenomenon in various animal groups.

Insects and arachnids are some of the most well-known cannibals in the animal world. Their small size, rapid reproduction rates, and high survival pressures make cannibalism a common survival strategy.

Praying Mantises often eat their mates during or after mating. This gruesome act provides the female with vital nutrients needed for egg production.

Black Widow Spiders are infamous for the female devouring the male post-mating, ensuring she has enough energy to care for her offspring.

Ladybugs sometimes consume their own eggs or larvae when food is scarce, using cannibalism to ensure their survival.

Grasshoppers can turn cannibalistic during droughts or food shortages, feeding on weaker members of their group.

scorpions.html">Scorpions may eat their own young if they experience stress or lack food, prioritizing their own survival over their offspring’s.

Fish and amphibians exhibit cannibalism for reasons like population control or survival in harsh environments. It’s not uncommon for these species to consume their own kind when food becomes limited.

Tiger Salamanders have larvae that will eat their siblings when food is scarce, ensuring that only the strongest survive.

Guppies sometimes consume their own fry (offspring) to reduce competition for food and resources.

African Clawed Frogs are known to eat their tadpoles when living in crowded conditions.

Sand Tiger Sharks practice intrauterine cannibalism, where the strongest embryo eats its siblings in the womb, ensuring only the fittest are born.

Bullfrogs will eat smaller frogs, including members of their own species, to reduce competition.

Cannibalism in birds is less common but does occur, usually under extreme conditions like food shortages or high levels of stress.

Seagulls have been observed eating the chicks of their species when food is limited.

Chickens may turn cannibalistic in overcrowded environments, attacking and eating weaker birds.

Eagles sometimes eat their own chicks if they are weak or sick, ensuring that only the strongest survive.

Pelicans may consume their eggs or chicks if they feel threatened or stressed.

Owls sometimes exhibit siblicide, where one sibling eats another when food supplies are low.

Cannibalism is much rarer in mammals, but it does happen, often as a desperate measure for survival in extreme conditions.

Polar Bears have been known to eat their cubs during times of extreme food scarcity, especially when hunting is difficult in the harsh Arctic environment.

Lions may kill and eat the cubs of rival males to bring females back into heat and increase their chances of mating.

Chimpanzees sometimes engage in cannibalism during territorial disputes, where they consume the infants of rival groups.

Rats are known to eat their young when they are stressed or lacking food, sacrificing some offspring to ensure the survival of others.

Hamsters may consume their babies if they feel threatened or if the litter is too large to care for.

Cold-blooded reptiles also engage in cannibalism, especially as a means of survival when food is scarce or when territorial disputes arise.

Komodo Dragons are known to eat their own young, which is why juvenile Komodos often take refuge in trees to avoid being eaten by adults.

Crocodiles may eat smaller or weaker members of their own species during droughts or food shortages.

King Cobras will eat other snakes, including their kind, to eliminate competition for food and territory.

Geckos may consume their eggs or young if resources are scarce, ensuring their own survival in tough times.

Turtles have been observed eating hatchlings, especially in crowded or resource-limited environments.

The ocean is a vast and competitive world where cannibalism is often a survival strategy for many marine species.

Octopuses are known to eat their kind, particularly during the breeding season when competition is high.

Crabs often consume weaker members of their species or even their own young in crowded environments.

Lobsters will eat each other when food is scarce or when kept in close quarters without adequate resources.

Sea Stars sometimes engage in cannibalism, particularly when food is hard to find.

Squids can turn cannibalistic in times of food shortage, eating smaller or weaker individuals in the group.

Insects are notorious for cannibalism, and their behaviors often revolve around survival, particularly in overcrowded environments or during food shortages.

Ants will eat injured or dead members of their colony to recycle nutrients back into the group.

Bees may consume their larvae when the hive is under threat or facing starvation.

Termites engage in cannibalism to maintain the health of their colony by eating sick or dead members.

Butterflies in their larval stage may consume their own eggshells or even other larvae when food is scarce.

Cockroaches turn cannibalistic in overcrowded or food-scarce environments, feeding on each other to survive.

Amphibians display a variety of cannibalistic behaviors, often driven by environmental pressures such as overcrowding or limited food supply.

Newts may consume their eggs or larvae in environments with scarce food.

Toads sometimes engage in cannibalism by eating their tadpoles to reduce competition for limited resources.

Caecilians, a legless amphibian, will eat their young when under stress or in difficult conditions.

Axolotls turn cannibalistic in overcrowded tanks or environments, eating smaller or weaker individuals.

Tree Frogs occasionally consume their eggs or tadpoles, especially in dry seasons or during food shortages.

Reptiles exhibit cannibalism in a variety of forms, and it’s often a response to environmental stressors such as overcrowding, competition, or food scarcity.

Like their crocodile relatives, alligators sometimes consume younger or smaller members of their species. This behavior occurs during times of drought when food is scarce.

Green iguanas, when housed in captivity in large numbers, can turn cannibalistic if food becomes insufficient. Juveniles are often the targets of adult iguanas during times of food competition.

Monitor lizards, including the massive Komodo dragon, have been documented eating their own young or weaker individuals. Younger lizards will often take to the trees to avoid predation by adults.

Anole lizards, common in warm climates, have been observed consuming smaller members of their species, especially when food resources become limited in their environments.

Though mammals are less commonly associated with cannibalism, it can still occur in more species than one might think, especially when survival becomes desperate.

Wolves may sometimes resort to cannibalism, particularly when pack dynamics break down due to food shortages or conflict. Weaker members, or even pups, can be consumed.

Rabbits, often seen as gentle creatures, can exhibit cannibalism under certain conditions, particularly in overcrowded colonies or when nursing mothers feel threatened. They may eat their own young if they sense the litter is too large to care for effectively.

Domestic pigs are known for cannibalism, especially in confined environments. Overcrowding and competition for resources can lead to aggressive behavior, where weaker individuals may be attacked and eaten.

Meerkats have been known to kill and consume rival pups. This behavior ensures that the alpha female’s offspring have the best chances of survival by reducing competition within the group.

In certain cases, prairie dogs may kill and cannibalize pups from neighboring colonies to reduce competition and ensure that resources are concentrated within their own group.

The ocean, as a vast and competitive habitat, is home to many species that engage in cannibalism. With constant battles for survival, marine life often exhibits this behavior as a means of controlling populations or ensuring the fittest survive.

Barracudas, known for their aggressive hunting style, have been observed engaging in cannibalism. Juvenile barracudas are sometimes eaten by adults, especially during times of resource scarcity.

Groupers, large predatory fish, have been known to engage in cannibalism, particularly when food becomes scarce. Juvenile groupers may be consumed by adults, allowing only the strongest individuals to thrive.

Some species of shrimp will cannibalize their own kind, especially in crowded environments where competition for resources is high. This behavior is common in both wild and captive populations.

Hermit crabs have been observed engaging in cannibalism, particularly during molting periods when individuals are most vulnerable. Cannibalistic behavior helps reduce competition for valuable shells in their environment.

Clownfish are known to consume their own eggs, particularly if they feel threatened or stressed. This behavior helps conserve energy by eliminating offspring that are unlikely to survive.

Cannibalism is incredibly common among insects, especially in species where high reproduction rates and environmental pressures require survival strategies that include eating weaker individuals or even offspring.

Locusts, a type of grasshopper, are known to turn cannibalistic during plagues when food resources are depleted. This behavior helps them survive during migrations and periods of extreme scarcity.

In addition to eating each other during overcrowded conditions, cockroaches are also known to consume their own egg cases in times of extreme food shortages.

Mosquito larvae have been observed engaging in cannibalism in their aquatic environments. The larger larvae may consume smaller ones, reducing competition and increasing their chances of reaching adulthood.

Various species of beetles, including the American burying beetle, practice cannibalism. Female beetles will sometimes consume their offspring if they determine that they will not survive, using the energy to care for healthier young.

The larvae of ant lions are notorious for cannibalistic behavior. They often consume other ant lions when they fall into the same sandpit, using this as an opportunity to eliminate competition.

Amphibians exhibit cannibalism as a way of coping with environmental stressors, including food shortages and competition for limited resources in their habitats.

Cannibalism among salamanders is well-documented, especially among larvae. When food is scarce, larger larvae will prey on their smaller siblings, ensuring that only the strongest survive.

Some tree frogs will consume their eggs or tadpoles during periods of environmental stress, particularly in overcrowded breeding sites or during droughts. This behavior helps control population density.

Caecilians, a lesser-known group of legless amphibians, will sometimes consume their young or eggs in response to environmental pressures, such as lack of food.

Cannibalism plays a significant role in maintaining the balance of ecosystems. It might seem gruesome from a human perspective, but in the wild, it is a natural part of life for many species. Here’s why cannibalism is crucial for survival:

Population Control: Cannibalism helps regulate population sizes, preventing overcrowding and the depletion of resources. In ecosystems where resources are limited, this can be the difference between survival and extinction.

Survival of the Fittest: In some species, cannibalism ensures that only the strongest individuals survive. By eliminating weaker members, animals increase the chances that their genes will be passed on to the next generation.

Energy Conservation: In certain circumstances, consuming offspring or weaker individuals helps conserve energy. For instance, female insects may eat their mates or young to gain nutrients for reproduction or future offspring.

Reducing Competition: Cannibalism can eliminate competition for food and territory, which is especially important in crowded environments or during periods of scarcity.

Cannibalism may seem horrifying to us, but in the animal kingdom, it’s an essential part of survival. From insects to mammals, reptiles to marine life, animals engage in this behavior for various reasons—whether to ensure their own survival or the survival of their species.

As unsettling as it may be, cannibalism helps maintain ecological balance by reducing competition, conserving resources, and ensuring that only the strongest individuals reproduce. The next time you watch a wildlife documentary or read about these creatures, remember that behind their survival tactics lies a complex web of behaviors that keep ecosystems functioning—even if that means resorting to cannibalism.

Nature is not just about beauty and wonder—it has a dark side too, and understanding it deepens our appreciation of how life continues in even the harshest environments.

While cannibalism occurs widely in the animal kingdom, humans generally avoid this behavior due to a variety of biological, social, and cultural reasons. Let’s explore why cannibalism, which seems so prevalent and sometimes necessary in nature, is almost universally rejected by humans.

One of the main reasons humans don’t engage in cannibalism is the high risk of disease transmission, especially of prion diseases. Prions are abnormal proteins that can cause severe neurodegenerative diseases. One infamous example is Kuru, a deadly disease that affected the Fore people of Papua New Guinea, who practiced ritualistic cannibalism. Kuru spread through the consumption of human brain tissue, leading to a 100% fatality rate. Other prion diseases, like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, can similarly be transmitted through cannibalism.

In contrast, most animals have evolved to deal with the pathogens present in their species or are opportunistic cannibals who eat each other sparingly or under duress.

Humans have strong psychological and moral aversions to cannibalism. Over time, society has developed deep-rooted taboos against the practice. From an evolutionary standpoint, avoiding cannibalism may have offered survival advantages, ensuring that humans did not consume infected or diseased individuals.

For most people, the thought of eating another human evokes feelings of disgust, horror, and even panic—reactions that are deeply ingrained. This emotional response is supported by moral and ethical frameworks that value human life and dignity, making cannibalism a violation of social norms.

Cannibalism is often seen as socially disruptive. In human societies, communal living, cooperation, and mutual protection are key to survival. Cannibalism, in contrast, undermines social structures and threatens group cohesion.

Throughout history, humans developed cultural practices and laws that prohibit cannibalism. Religious and legal systems around the world typically view it as a severe crime, reinforcing a strong cultural stigma. While there have been exceptions in extreme survival situations (such as in cases of shipwrecks or plane crashes), these instances are rare and usually followed by significant psychological trauma for the survivors involved.

For animals, cannibalism can be a survival strategy in cases of extreme need, such as during food shortages, overcrowding, or environmental stress. In contrast, humans have developed alternative survival mechanisms like agriculture, hunting, and food preservation. These innovations have reduced the need for extreme measures like cannibalism.

In rare cases of human cannibalism, it has generally been under extreme duress, like the Donner Party in the 1800s, where people resorted to cannibalism during a harsh winter when no other food source was available. Even in these cases, cannibalism is seen as a last resort, highlighting its social and psychological burden.

Another important difference is that humans form deep emotional and social bonds with others, making the idea of eating another person not only unthinkable but emotionally devastating. Cannibalism would erode these bonds of trust and care, leading to a breakdown in the social fabric that supports human cooperation and survival.

Animals, especially those that practice cannibalism, may not have the same level of emotional attachment to their offspring or group members, allowing for cannibalistic behavior in certain contexts without the same psychological toll.

Animals rely on survival instincts rather than moral codes, and in many cases, cannibalism can be a natural strategy for survival, population control, or reproduction. Whether it’s due to scarcity of food or environmental stress, animals engage in cannibalism out of necessity, and many species are biologically equipped to handle the risks associated with it.

Humans, on the other hand, have evolved complex societies with agriculture, moral codes, and medical knowledge. We know the biological dangers of cannibalism (such as disease transmission), and we’ve developed deep psychological barriers and legal structures that prevent it from becoming a widespread practice.

Cannibalism in the animal kingdom serves as a survival mechanism, but humans generally avoid it due to the biological risks, strong psychological and cultural barriers, and our ability to find other ways to survive. The few instances of human cannibalism typically occur in extreme situations, and they carry a heavy social and emotional toll, often seen as a last-ditch effort for survival.

For humans, cannibalism isn’t just a biological risk—it’s also a violation of deeply held values that separate us from other species. This combination of factors explains why cannibalism is largely absent in human societies, even though it remains a common behavior in the animal world.

animal tags: Cannibalism

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.