Frogs are widely distributed amphibians whose lives are tightly tied to water. Their development features a dramatic metamorphosis: from egg to tadpole, then to froglet and land-capable adult. Timelines and details vary by species, but the overall path is consistent. As both predators and prey, frogs are vital for ecosystem balance and wetland health.

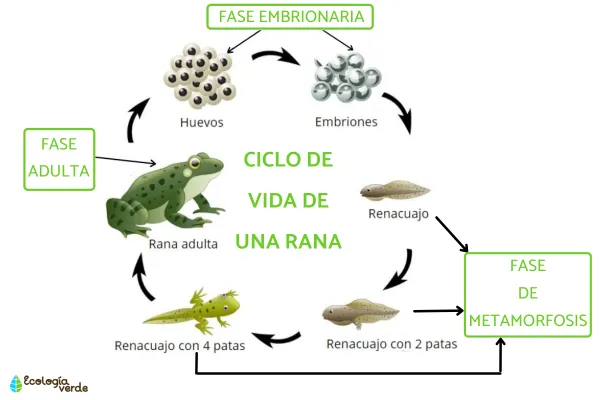

Life cycle at a glance (flow & image plan)

Stage 1 — Spawning & Embryonic Development

Stage 2 — From Egg to Tadpole (Hatching)

Stage 3 — Metamorphosis: Tadpole → Froglet

Stage 4 — Adult Stage & Reproduction

FAQs & publishing tips

Summary

Standard sequence:

Spawning/Embryo → Hatching to Tadpole → Metamorphosis to Froglet → Adult Reproduction → Spawning again

Most species use external fertilization: during amplexus (the male clasping the female), sperm is released over the eggs in water.

The cycle repeats throughout the adult’s life, with many breeding events possible.

Suggested image placements (for easy browsing):

Fig. 1: Ring diagram of the life cycle (egg mass → tadpole → hind legs → four legs → tail resorption → froglet → adult → spawning).

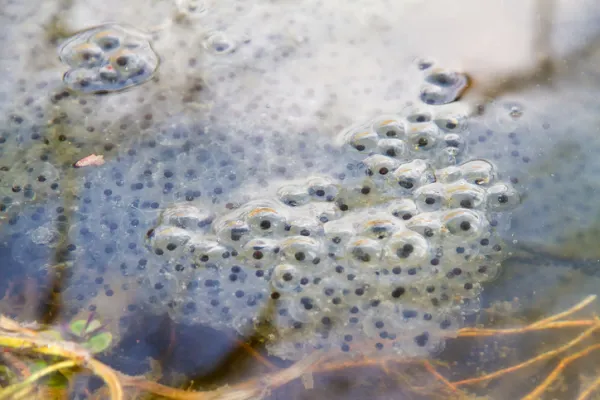

Fig. 2: Egg mass close-up (clear jelly with visible embryos).

Fig. 3: Classic tadpole (tail fin, external/internal gills).

Fig. 4: Metamorphosis series (hind legs first, then forelegs, tail shrinking).

Fig. 5: Amplexus during breeding.

Alt text examples:

“Transparent jelly-coated frog egg mass with developing embryos in shallow water.”

“Tadpole with long tail fin grazing on algae.”

“Hind legs emerging in a tadpole; tail gradually resorbing.”

Oviparous reproduction: Eggs are laid in or on water, often in clusters or strings bound by jelly that keeps them moist, cushioned, and together.

R-strategy: Many eggs, minimal parental care—quantity compensates for high early mortality.

Yolk (vitellus): provides nutrients; early embryos display bilateral symmetry.

Key embryonic steps (plain-language):

Cleavage & blastula: The fertilized egg divides into a solid morula and then a hollow blastula.

Gastrulation: Cells fold inward to form the germ layers—

Endoderm: digestive tract and other internal organs;

Ectoderm: skin and nervous system precursors.

Notochord formation: establishes the body axis and triggers nervous system development (frogs, like us, are chordates).

Mesoderm formation: gives rise to circulatory system, muscles, kidneys, etc.

Environment matters: temperature, water quality, and dissolved oxygen influence development speed and hatching success.

When embryonic development is sufficient for independent survival, the egg membrane breaks and tadpoles emerge. This stage is fully aquatic:

Body plan: Large tail fin, no limbs at first, gill breathing (initially external gills, then internal).

Habitat & diet: Shallow, still or slow-moving water; many species feed mainly on algae, biofilm, plankton, and detritus (varies by species).

Ecology: Tadpoles (aquatic, mostly herbivorous) and adults (water–land edge, mostly carnivorous) occupy different niches, reducing parent–offspring competition.

During metamorphosis, the tadpole undergoes major morphological and physiological remodeling to adopt a semi-terrestrial lifestyle:

Limb formation

Hind legs appear first, then forelegs; bones and muscles mature for jumping and climbing.

Tail resorption

The tail fin is broken down and reabsorbed (programmed cell death), recycling nutrients to fuel growth.

Respiratory shift

Gills regress as lungs develop; adults rely on dual respiration—lungs + moist skin for gas exchange.

Circulatory rewiring

Blood flow patterns adjust to the new respiratory organs (amphibians typically have a three-chambered heart).

Other changes

Eyes and ears refine for land;

Vocal apparatus (and, in many males, vocal sac) develops for calls;

Skin thickens and pigments, improving protection and camouflage;

Mouthparts & gut shift from plant-leaning to animal-prey diets.

Timing: Species, temperature, food availability, and water levels can stretch metamorphosis from weeks to several months.

Niche shift: Adults live along the water–land ecotone, roam more widely, and feed mostly on invertebrates (e.g., insects).

Courtship & amplexus:

Males call and display territories to attract females.

During amplexus, the male clasps the female beneath the forelimbs; eggs are laid as the male releases sperm (external fertilization).

Spawning & repeat: Fertilized eggs are attached to plants or substrates in or on water, returning the cycle to Stage 1.

How long until a tadpole becomes a froglet?

It varies widely—weeks to months—depending on species, temperature, food, and water stability. Warmer, well-fed, stable conditions usually accelerate development.

Can tadpoles leave the water?

Not in early stages. They rely on gill respiration and must stay aquatic. Near the end of metamorphosis—four limbs present and tail nearly resorbed—they transition to lung + skin breathing and begin land activity.

Do all frogs hibernate?

No. Many temperate species hibernate or enter dormancy in cold seasons; tropical species may remain active year-round or estivate during severe drought.

Why are frogs so noisy after rain?

Rain boosts humidity and water levels, improving egg and embryo survival—males chorus to attract mates during peak breeding windows.

Publishing tips (for your CMS/SEO):

Add clear images/illustrations for each stage with descriptive alt text.

Useful internal links:

“How Amphibians Breathe”

“Butterfly Life Cycle: Stages & Images”

“What Counts as an Amphibian & Where They Live.”

The frog life cycle showcases a classic water-to-land transformation: nutrient-rich eggs hatch into aquatic tadpoles, which metamorphose into froglets and then adults that straddle water and land. Understanding each stage helps schools, communities, and conservation projects protect wetlands and shallow-water habitats so more amphibians can successfully complete this remarkable journey.

animal tags: frog

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.