Within aquatic ecosystems, there are countless tiny animals that escape our naked eye. Among these, copepods (Copepoda) are some of the most essential microscopic crustaceans, distributed throughout the world's freshwater, marine, and brackish environments. With over 21,000 known species, copepods are not only incredibly abundant, but also play a vital role in aquatic food webs. This article will introduce you to the basic features, classification, habitat, diet, reproduction, and ecological importance of copepods.

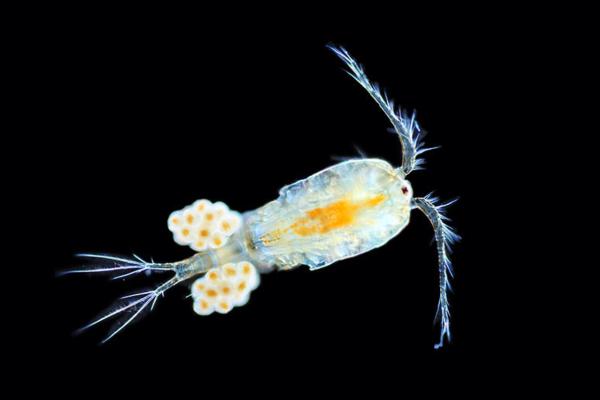

Copepods are minute crustaceans, members of the subphylum Crustacea, but they differ significantly from larger, familiar crustaceans like crabs and lobsters. Their bodies are usually drop-shaped or spindle-shaped and range from 0.25 to 3 millimeters in length—so small they are often only visible under a microscope. Key features of copepods include:

No protective carapace: Unlike many crustaceans, copepods lack a hard dorsal shell.

Two long antennae: In some species, one pair is highly developed and used for swimming.

Furcal rami (caudal branches): These forked tail-like appendages, often with bristles, help with balance.

Multiple appendages: Head appendages mainly serve for feeding, while abdominal appendages are used for swimming.

Typically transparent: Though most copepods are colorless or transparent, some can appear red, blue, or green.

Extremely small size: Making them typical members of aquatic microfauna.

Copepods are a highly diverse group, and their classification can be based on lifestyle, habitat, and anatomical characteristics:

Free-living copepods: The vast majority, comprising much of the plankton in both freshwater and marine environments.

Parasitic copepods: Some species live attached to or inside fish, mollusks, or other animals.

Freshwater copepods: Found in lakes, rivers, ponds, and streams.

Marine copepods: Found throughout the world’s oceans, from surface waters to deep sea.

Brackish water copepods: Thrive in estuaries and environments with variable salinity.

Planktonic copepods: Drift near the water’s surface and form a major part of zooplankton.

Benthic copepods: Live on or within sediment at the bottom of bodies of water.

Interstitial and semi-terrestrial copepods: Some species live in moist soils, plant water pockets, or rock crevices.

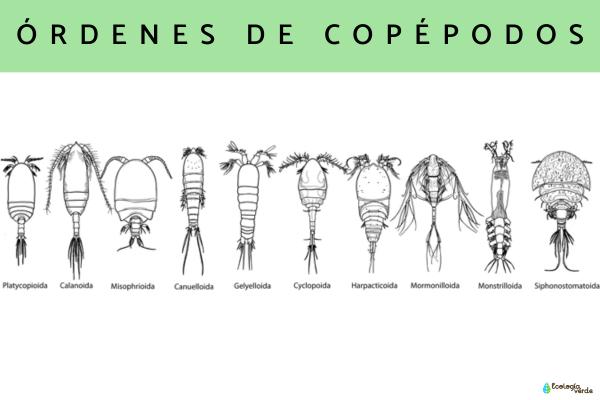

Calanoida: Possess very long antennae; most are free-living and marine plankton.

Cyclopoida: Shorter antennae; found in both fresh and marine waters, includes free-living and parasitic species.

Harpacticoida: Stout-bodied and often benthic, living among sediments or aquatic vegetation.

Siphonostomatoida: Mostly parasitic, often on fish.

Other orders such as Monstrilloida, Poecilostomatoida, and Platycopioida have unique ecological and morphological adaptations.

Copepods are among the most widely distributed animals on Earth. From the equator to the poles, high mountain lakes to rain forest plant water tanks, you can find copepods almost anywhere with water. Typical habitats include:

Lakes, rivers, ponds, and streams (freshwater)

Oceans and seas (marine)

Brackish estuaries

Polar waters, tropics, and alpine lakes

Plant water reservoirs (phytotelmata)

Zooplankton: Free-living copepods make up about 50% of marine zooplankton and up to 96% of zooplankton in continental waters.

Copepod feeding habits are varied depending on the species:

Free-living copepods: Many are filter feeders, using their antennae and mouthparts to create currents that capture tiny phytoplankton and organic particles. Others are active predators, feeding on smaller zooplankton.

Parasitic copepods: Live on or inside fish, mollusks, or other animals. Some are harmless commensals, while others harm their hosts by feeding on tissue or fluids.

Copepods have a complex life cycle:

Mating: Males transfer a spermatophore (sperm packet) to the female using modified antennae.

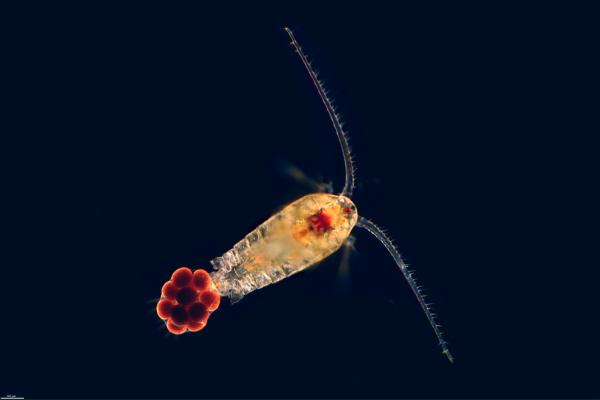

Egg-laying: Some species release fertilized eggs directly into the water, while others carry egg sacs attached to their bodies until hatching.

Development: Eggs hatch into a larval stage called the nauplius, which has only a head and tail. After multiple molts, it transforms into a copepodite, and eventually an adult.

This entire process—from egg to adult—can take anywhere from a few weeks to a year, depending on species and environmental conditions.

Copepods are crucial links in aquatic food webs, transferring energy from primary producers (phytoplankton) to higher consumers (fish, whales, etc.). Their roles include:

Main food source for many fish larvae, juvenile crustaceans, and baleen whales.

Help control algal populations by grazing on phytoplankton, contributing to water quality.

Widely used in aquaculture as a nutritious live feed for hatchery-reared fish and shrimp.

Some parasitic species serve as indicators of fish health in aquaculture and wild fisheries.

Copepods are among the most abundant and ecologically significant microscopic animals on the planet. Understanding their diversity, ecological roles, and life history not only enriches scientific research but also benefits aquaculture and environmental conservation. For more in-depth information on animal biodiversity, feel free to explore our website’s "Wild Animals" section!

Bibliography

Suárez, E., Velázquez, K., Ayón, M. (2021). Catalog of copepods (Crustacea: Copepoda: Calanoida and Cyclopoida) from temporary water bodies in Jalisco. Mexico: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur.

animal tags: Copepods

We created this article in conjunction with AI technology, then made sure it was fact-checked and edited by a Animals Top editor.